Document 10464580

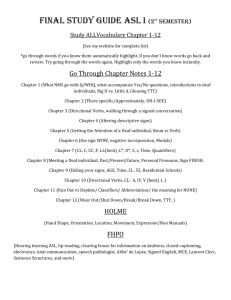

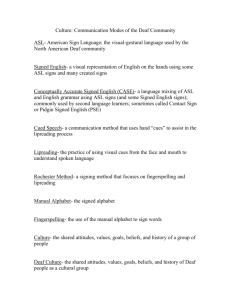

advertisement