SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY: A Career That Makes a Difference PRESENTER:

advertisement

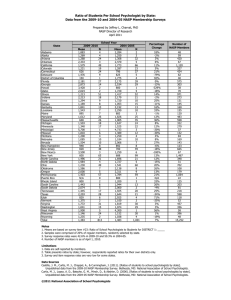

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY: A Career That Makes a Difference © 2010 National Association of School Psychologists PRESENTER: If you want to … • Help children reach their potential • Promote children’s mental health and academic competence • Work collaboratively with parents, school staff, and community agencies for children • Have a variety of career options, including working in schools or as a professor or researcher in a university setting then… School Psychology could be the career for you! 2 Who are school psychologists? School Psychologists understand that all children learn when given: • Adequate supports and resources • Recognition of their individual needs • Connection to and trust in adults • Affirmation of their cultural and individual distinctiveness • High expectations and encouragement 4 School Psychologists link mental health to learning and behavior to promote: • High academic achievement • Positive social-emotional skills and behavior • Healthy relationships and connectedness • Tolerance and respect for others • Competence, self-esteem, and resilience 5 When do children need a School Psychologist? Learning difficulties Behavior concerns Problems at home or with peers Depression and other mental health issues Coping with crisis, transitions, or any other life changing event • Coping with poverty, violence and other environmental stressors • • • • • 6 What is the role of a School Psychologist? • Assessment for educational planning (e.g., academic skills, behavior and social-emotional development, special education eligibility) • Consultation with school and community • Prevention • Intervention • Staff, parent, and student education • Research and program development • Advocacy • Systems change 7 Where do School Psychologists work? • • • • • • • • • Public and private schools Colleges and universities Institutional/residential facilities Criminal justice system Community mental health centers Public agencies Pediatric clinics and hospitals Private practice Test and curriculum publishing companies 8 What are some reasons people choose school psychology as a career? “I wanted a career that focused on youth advocacy in the schools but would allow me to integrate my passion for cultural awareness, equity and diversity into the school community.” --Christina Noel, School Psychologist, Dartmouth, MA Why We Need You: Current Demographics Demographic Variable* U.S. Population (2007) School Psychologists (2005) Female Gender 50.7% 74.0% White/Caucasian 66.0% 92.6% Latino 15.1% 3.0% Black 12.3% 1.9% Asian American/Pacific Islander 4.4% 0.9% Indigenous American 0.8% 0.8% Other 1.4% 0.8% *Race categories exclude persons of Latino ethnicity Percentages are based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau (2007). Curtis et al. (2008) 10 Diversity in the Workforce Needed “The field of school psychology has been largely Caucasian throughout its history… Although individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds and those fluent in languages other than English continue to be seriously underrepresented in the field, many school psychologists work in settings in which they serve an increasingly diverse student population.” (Curtis, Grier, & Hunley, 2004, p. 52) 11 Greater Number of Bilingual School Psychologists Needed • 10.8 million children in U.S. public schools speak a language other than English at home, and 25% of them speak English with difficulty (U.S. Dept. of Education, 2008). • 11% of NASP regular members are fluent in a language other than English (NASP, 2008). • Of 30 languages reported by NASP regular members, the top 3 are Spanish (48%), French (13%), and American Sign Language (8%) (NASP, 2008). • 55% of the NASP members who are fluent in a language other than English provide psychological services to students/families in that language (Curtis et al., 2008). 12 Real Challenges: You can make a difference • Asian Americans speak more than 100 languages, and 40% of Chinese American households are linguistically isolated, as the only or one of few households in a district that speak their perspective language • About 1 out of 2 Asian Americans have difficulty accessing mental health treatment due to limited English ability—approximately 70 providers for every 100,000 in need (SAMHSA, 2008) 13 Real Challenges: You can make a difference • Black children are over 4 times more likely to be identified for special education programs based on intellectual limitations or emotional disabilities • A Black male born in 2001 has a 1 in 3 chance of going to prison in his lifetime, and his female counterpart has a 1 in 17 chance—up to 5 times more likely than other cultural groups (Children’s Defense Fund, 2007) 14 Challenges (continued) • 1 in 4 Latino children are born into poverty and are therefore 3 times more likely to drop out of school • 16% of Latino 4th graders are reading at grade level, and 15% are performing at grade level in math (Children’s Defense Fund, 2007) • Youth aged 12-17 who identify as two or more races have a Major Depressive Episode rate almost twice as high as single race youth—13% (SAMHSA, 2008) 15 Challenges (continued) • Indigenous Americans aged 12-17 experience about twice the overall rate of illicit drug use for all youth—18.7% (SAMSHA, 2008) • 18% of Indigenous American students have been retained in the same grade at least once, compared to 17.5% of Black students, 13.2% of Latinos, and 9.3% of Whites (Children’s Defense Fund, 2007) 16 School Dropout Rates Race/Ethnicity* Percentage of Students (2006) Latino 22.1% Indigenous American 14.7% Black 10.7% White/Caucasian 5.8% Asian American/Pacific Islander 3.7% Other 7.0% *Race categories exclude persons of Latino ethnicity (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2008) 17 Where do most children and families receive support? • Of the average 3.3 million youth age 12-17 who need specialty mental health and education services a year, about 3 million of them receive only school-based care (SAMHSA, 2008) School Psychology May Be a Key Part of the Solution—But We Need Your Help. 18 Importance of Diversity in School Psychology • School Psychologists serve an increasingly diverse student population (Curtis et al., 2004). • There is a wide gap between ethnic and linguistic diversity of School Psychologists and students (Curtis et al., 2008). • People of color often express preference for therapists of the same background (Whaley, 2001). • More than one third of School Psychologists receive only one or no diversity training experiences (Loe & Miranda, 2005). 19 Children and families from all backgrounds need to be supported by School Psychologists who understand their experiences, beliefs, and concerns. “As a Diné (Navajo) School Psychologist, I am working back in my ancestral homeland with my people, using my cultural knowledge and indigenous language to provide a diverse service delivery. I am making a difference by being accessible.” --Elvina Charley, EdS, School Psychologist, Chinle, AZ (Rosebud Lakota Flag, 2007) 21 Career Opportunities • Ethnically and linguistically diverse practitioners are underrepresented in the field (Curtis et al., 2004). • Excellent employment outlook. Shortage of almost 15,000 school psychologists by 2020; ongoing shortage of university faculty (Curtis et al., 2004). • School Psychology named one of the “Best Careers for 2009” by U.S. News and World Report (Wolgemuth, 2008) 22 Salaries of School Psychologists • Practitioners: Mean = $62,513 • University Faculty: Mean = $65,398 • Top salaries exceed $100,000. • Salaries vary by state and region. (Curtis et al., 2007) 23 School Psychology A Great Career Choice • • • • • • Work with children who need you Help parents and educators Enjoy a flexible school schedule Have a variety of responsibilities Receive training in useful skills Choose from a variety of work settings 24 So how do I become a School Psychologist? Undergraduate Training • Consider an education, psychology, or related undergraduate major • Take courses in » » » » » » » Child development General and child psychology Statistics, measurement, and research Philosophy and theory of education Instruction and curriculum Special education Ethnic studies or cultural diversity • Complete a Bachelor’s degree program 26 Graduate Training Degree Options • Education Specialist » In most states, certification as a School Psychologist requires training at the specialist level. » Specialist-level training includes 60 graduate semester credits in school psychology » Specialist-level degrees can be identified by several acronyms, including Educational Specialist (EdS), Master’s (MA, MS, MEd), Certificate of Advanced Graduate Studies (CAGS/CAS), etc. - or • Doctorate (PhD, PsyD or EdD) 27 Applying to a Graduate Program • GRE: Graduate Record Exam » Some programs may require the GRE—Psychology • Undergraduate transcripts • Letters of recommendation • Personal statement(s) • Practice or research interests 28 NASP Minority Scholarship Program • To foster diversity among professional school psychologists, NASP offers annual $5,000 scholarships to CLD students pursuing careers in school psychology • Only students who are NASP members and pursuing specialist-level graduate training in school psychology are considered for the award • For more information or an application, see www.nasponline.org/about_nasp/minority. aspx 29 QUESTIONS? 30 Interested in a School Psychology Career? • Visit NASP’s Facebook Page • Become a NASP Student Associate Member and receive access to all member benefits. • For membership benefits and enrollment information link to: www.nasponline.org/membership/benefits.aspx References Children’s Defense Fund. (2007). A report of the Children’s Defense Fund: America’s cradle to prison pipeline. Washington, D.C. Curtis, M. J., Grier, J. E. C., & Hunley, S. A. (2004). The changing face of school psychology: Trends in data and projections for the future. School Psychology Review, 33, 49-66. Curtis, M. J., Hunley, S. A., & Grier, J. E. C. (2004). The status of school psychology: Implications of a major personnel shortage. Psychology in the Schools, 41, 431-442. Curtis, M. J., Lopez, A. D., Batsche, G. M., Minch, D., & Abshier, D. (2007, March). Status report on school psychology: A national perspective. Paper presented at the annual convention of the National Association of School Psychologists, New York City. Curtis, M. J., Lopez, A. D., Castillo, J. M., Batsche, G. M., Minch, D., & Smith, J. C. (2008). The status of school psychology: Demographic characteristics, employment conditions, professional practices, and continuing professional development. Communiqué, 36, 27-29. Loe, S. A., & Miranda, A. H. (2005). An examination of ethnic incongruence in school-based psychological services and diversity-training experiences among school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 419-432. 32 References National Association of School Psychologists. (2008). [Fluency in and use of languages other than English among NASP members.] Unpublished data from the 2004-05 NASP Membership Survey. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2008). Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343). Rockville, MD: Author. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. (2007). Annual estimates of the population by sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States: April 1, 2007 to July 1, 2007 (NC-EST2007-03). Washington, DC: Author. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2008). The condition of education 2008 (NCES 2008-031). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Whaley, A. L. (2001). Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African Americans: A review and meta-analysis. Counseling Psychologist, 29, 513-531. Wolgemuth, L. (2008, December 11). The 30 best careers for 2009. U.S. News & World Report. 33 For More Information Contact: National Association of School Psychologists www.nasponline.org/about_sp/spsych.aspx (301) 657-0270 Please complete today’s presentation evaluation form.

![[Today’s Date] [Your Supervisor’s First Name] [Your School or District’s Name]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010451343_1-ed5410b4013e6d3fbc1a9bbd91a926a9-300x300.png)