PUBLIC UTILITIES IN THE WEST BANK AND GAZA STRIP

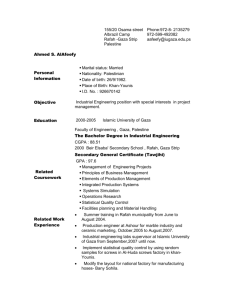

advertisement