Changing Retail Composition in Greenwich, Connecticut 2000 – 2013

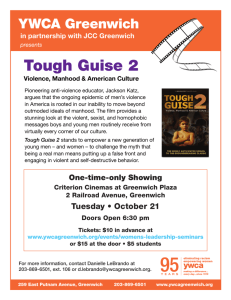

advertisement