CITY OF CAPE TOWN RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE FORESHORE FREEWAY SCHEME

advertisement

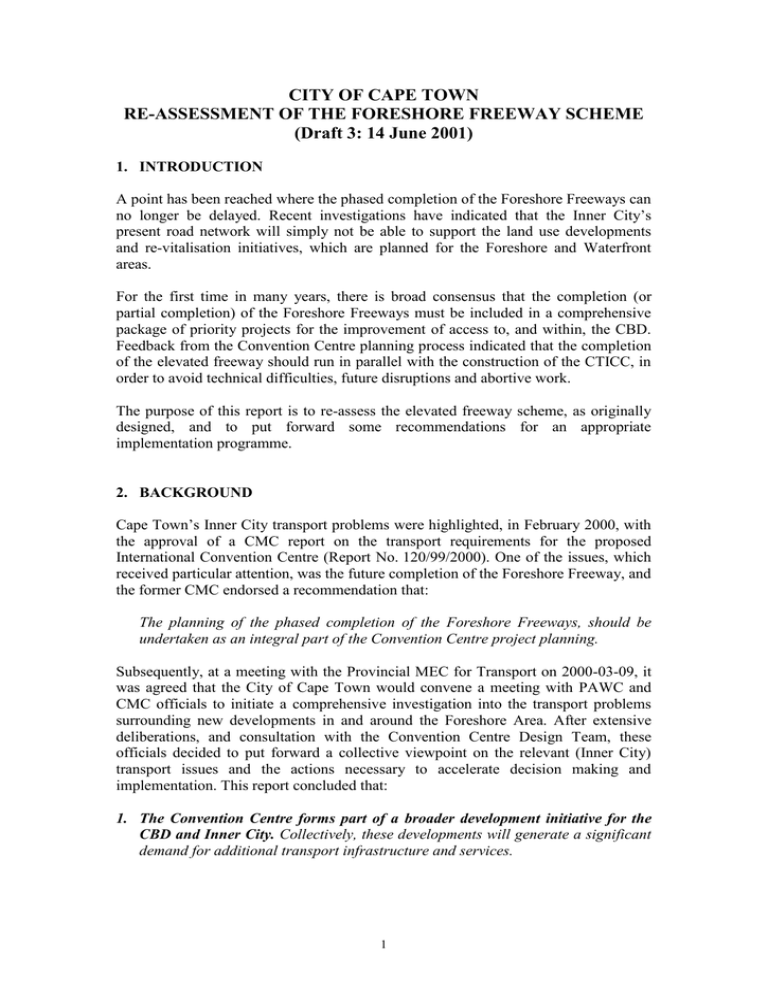

CITY OF CAPE TOWN RE-ASSESSMENT OF THE FORESHORE FREEWAY SCHEME (Draft 3: 14 June 2001) 1. INTRODUCTION A point has been reached where the phased completion of the Foreshore Freeways can no longer be delayed. Recent investigations have indicated that the Inner City’s present road network will simply not be able to support the land use developments and re-vitalisation initiatives, which are planned for the Foreshore and Waterfront areas. For the first time in many years, there is broad consensus that the completion (or partial completion) of the Foreshore Freeways must be included in a comprehensive package of priority projects for the improvement of access to, and within, the CBD. Feedback from the Convention Centre planning process indicated that the completion of the elevated freeway should run in parallel with the construction of the CTICC, in order to avoid technical difficulties, future disruptions and abortive work. The purpose of this report is to re-assess the elevated freeway scheme, as originally designed, and to put forward some recommendations for an appropriate implementation programme. 2. BACKGROUND Cape Town’s Inner City transport problems were highlighted, in February 2000, with the approval of a CMC report on the transport requirements for the proposed International Convention Centre (Report No. 120/99/2000). One of the issues, which received particular attention, was the future completion of the Foreshore Freeway, and the former CMC endorsed a recommendation that: The planning of the phased completion of the Foreshore Freeways, should be undertaken as an integral part of the Convention Centre project planning. Subsequently, at a meeting with the Provincial MEC for Transport on 2000-03-09, it was agreed that the City of Cape Town would convene a meeting with PAWC and CMC officials to initiate a comprehensive investigation into the transport problems surrounding new developments in and around the Foreshore Area. After extensive deliberations, and consultation with the Convention Centre Design Team, these officials decided to put forward a collective viewpoint on the relevant (Inner City) transport issues and the actions necessary to accelerate decision making and implementation. This report concluded that: 1. The Convention Centre forms part of a broader development initiative for the CBD and Inner City. Collectively, these developments will generate a significant demand for additional transport infrastructure and services. 1 2. A number of critical transportation planning issues need to be resolved as a matter of urgency, in order not to delay the implementation of the Convention Centre. Proposals for the completion of this work need to be endorsed. 3. The authorities will be obliged to commit additional funds for the phased implementation of the necessary transport infrastructure to support the Convention Centre and the future development of the Inner City. The exact nature, cost and timing of these investments are still to be determined, but it is expected to include: Local road improvements around the Convention Centre Parking and pedestrian facilities On-site public transport ranking and holding facilities Improved inner city public transport The phased completion of the Foreshore Freeway Investments on the main metropolitan road access corridors into the Inner City Rail investments These views were largely confirmed by the findings of the February, 2001 Transport Impact Assessment for the CTICC, which came out in strong support for the urgent completion of the Foreshore Freeway (particularly the internal viaduct and linking ramps towards Sea Point). This report also highlighted the need to proceed with plans to relieve the current bottlenecks at Koeberg and Marine Drive interchanges, and some form of grade separation of the through movements at the Oswald Pirow/ Table Bay Boulevard intersection. Failure to implement these infrastructure proposals will result in a significant increase in traffic congestion, over an extended peak period of up to three hours during the morning and afternoon commuter times. Such a scenario will however become counter-productive, and could in fact jeopardise the whole Inner City re-vitalisation programme, including the efficient operation of the Convention Centre. The transport authorities are therefore in general agreement that approval for the CTICC Transport Impact Assessment should be subject to an obligation by the participating authorities to commit the necessary funds for the phased completion of the Foreshore Freeway within the next few years. Certain elements of this work should in fact be accelerated to coincide with the building programme of the CTICC. Until a final decision is taken with regard to the form, function and extent of the future freeway completion, no permission will be granted for any projects that may jeopardise the original scheme. Any development proposals, which may lead to the alienation or use of land between the elevated freeway structures, will require the approval of all the relevant transport authorities. 3. THE PRESENT SCHEME The history of the Foreshore Freeway dates back to the early sixties when the Shand Report proposed an elevated freeway structure along the Foreshore, as part of a ring road concept for the CBD. Further investigations led to the evaluation of eight 2 different schemes, and the adoption of a 1968 report prepared by VKE Engineers, entitled: Report on the Preliminary Planning of Culemborg Viaduct, Table Bay and Buitengracht Freeways The preferred option, Scheme 3B, consisted of 3-lane outer viaducts (as presently constructed) and dual 4-lane inner viaducts with ultimate freeway connections to Sea Point and up along Buitengracht (Figure 1). The criteria used in this assessment included weave elimination, future capacity needs, lane balance and route continuity. Figure 1: Foreshore Freeway – Scheme 3B (ultimate) 2 4 2 3 2 4 3 3 2 3 NOTES: 2 2 2 2 1. LANE CONFIGURATION SHOWN IN CIRCLES 2. STAGE 1 STAGE 2 Future (1991) traffic forecasts were based on 1956 origin-destination surveys, and incorporated a city development strategy which was strongly focused towards intensified development and movement along the Buitengracht corridor. The planning also allowed for large-scale parking provision along this route (at that point in time, the Waterfront development was an unknown). Following from the above, the first phases of the elevated Foreshore Freeways were designed and constructed during the early and mid seventies, and included the following contracts: Contract 1: Contract 2: Contract 3: Contract 4: Contract 5: Hertzog Boulevard ramps Western Boulevard Outer elevated viaducts between Oswald Pirow and Buitengracht Coen Steytler Avenue Parking Garage Culemborg Viaduct 3 Implementation of the central viaducts and the ramp connections from the parking garage to the Western Boulevard (Contracts 6 and 7) were however delayed due to a lack of funds and limited justification in terms of the traffic demand at that time. Both contracts were fully designed and the construction drawings were completed in 1978. Planning also proceeded on Contract 8, the connections with Buitengracht. This resulted in the production of two reports: Report on the Buitengracht Traffic Study – VKE, Aug 1978 Addendum to Report on the Buitengracht Traffic study – VKE, November 1978 Both studies recommended an elevated grade separated scheme as far as Riebeeck Square. As in all previous reports, the assumptions were heavily biased towards intensified development and parking demand along this corridor. A lack of funds and environmental concerns however played a major role in discouraging any further progress and final decisions on this part of the freeway scheme. Large tracts of land were however acquired in the event that the scheme may still be implemented one day. During 1983 the City of Cape Town appointed consultants to review the CBD road system, including the Foreshore Freeway and its future Buitengracht connections. For the first time the City provided significantly revised land-use and parking projections, with one of the scenarios being a Foreshore-biased growth pattern (but excluding the V&A development). Conservation policies precluded full development along the Buitengracht corridor, and hence the number of trips which could be generated from this area. The following report was produced: Central City Traffic Study – Foreshore Freeway Consultants, April 1984 The main findings of this report were that: The elevated freeway along the Buitengracht need not be constructed, and the land may be released for development in keeping with the character of the immediate environment; There was no immediate need for the construction of the central viaducts of the Foreshore Freeway; The ramps linking Western Boulevard with the Foreshore Freeway should be constructed as an interim measure. Although the recommendations were not acceptable to the Provincial Roads Engineer at the time, it does appear that subsequent planning for the Olympic Bid Estimates (during 1996) convinced the authorities to accept a reduced Buitengracht Scheme, terminating just east of Riebeeck Street. 4 4. TRAFFIC ANALYSIS 4.1. Traffic Growth Traffic volumes on the Foreshore Freeway have grown steadily over the past twenty years, up to a point where both the N1 and Eastern Boulevard approach road systems have effectively reached their upstream capacity limits. In both instances, this capacity is in the order of 6 500 vehicles per hour, as governed by their present 3-lane cross-sections (see Figure 2). Figure 2: N1 / Eastern Boulevard Peak Hour Traffic Growth (am inbound) 8000 7000 6000 Veh/hr 5000 4000 3000 N1 Eastern Boulevard 2000 Capacity 1000 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987 1986 1985 1984 1983 1982 1981 1980 0 YEAR Figure 3: N1 / Eastern Boulevard 12-Hour Traffic Growth (inbound) 60000 12hr Traffic Volume 50000 40000 30000 N1 20000 Eastern Boulevard 10000 2000 1998 1996 1994 1992 1990 1988 1986 1984 1982 1980 0 YEAR By comparison, the 12hr traffic growth on both routes was in order of 60% for the 20year period between 1980 and 2000 (see Figure 3). If the same unconstrained growth could have applied to the peak hour traffic demand, then the N1 would presently have 5 carried about 8000 veh/hr and the Eastern Boulevard approximately 7200 veh/hr into the CBD during the morning peak period. For the purposes of this report, the term unconstrained refers to the latent peak hour traffic demand that could have used the Foreshore Freeway if it was not for the capacity constraints on the present approaches into the City. While further capacity improvements on the N1 may well be feasible, it is from an environmental point of view doubtful whether the Eastern Boulevard could be improved to accommodate more traffic than its present (3-lane) 6 500 veh/hr capacity limit. For the purposes of evaluating the Foreshore Freeways, it can therefore be assumed that the present unconstrained traffic demand on the N1 would be in the order of 8000 veh/hr. For the Eastern Boulevard it is assumed that present and future traffic demand will be restricted to 6500 veh/hr. These figures have been confirmed independently by Frieslaar and Jones, using a more sophisticated analysis for determining the traffic impact of the CTICC and other adjacent developments along the Foreshore. This methodology is explained in a paper entitled: Innovation Techniques used in the Traffic Impact Assessments of Developments in Congested Networks. 4.2. Present Traffic Demand Despite large daily fluctuations in traffic flow on the Foreshore Freeway, the most recent counts indicate that the present viaduct carries up to 5 000 veh/hr westbound during morning peak periods. At the eastern end, the incoming traffic is roughly divided in a 63:37 split between the N1 and Eastern Boulevard respectively. At the other end, recent surveys indicate a 24:25:23:28 split between the traffic destined for the Western Boulevard, Coen Steytler Avenue (eastbound), Dock Road and Buitengracht respectively. Present traffic demand, both constrained and unconstrained (in brackets), are summarised graphically in Figure 4. This clearly demonstrates the large latent demand for capacity improvements along the N1 corridor and its potential implications for the Foreshore Freeway. In fact, the present outer viaduct (3 lanes) and N1 approach ramps (2 lanes) will barely cope with the anticipated unconstrained traffic volumes. Figure 4: Foreshore Freeway Traffic Demand – 2001 am peak hour (bracketed figures indicate unconstrained demand) 5000 (6200) Western Boulevard Dock Rd 3150 (4000) Foreshore Freeway Coen Steytler (eastbound) Herzog Boulevard N1 1850 (2200) Eastern Boulevard Strand Buitengracht 6300 (6500) 6 6300 (8000) Due to the given capacity constraints along the Eastern Boulevard, it is assumed that traffic volumes along this route will not change significantly, or have a major impact on the future traffic growth projections for the Foreshore Freeway. 4.3. Summary of Demand Forecasts The present demand patterns, as shown in Figure 4, provide a valuable basis for assessing the Foreshore Freeway Scheme, particularly in terms of its original planning objectives more than 30 years ago. For this reason, a broad range of traffic data and projections from previous studies are summarised in Tables 1 and 2 for west and eastbound directions respectively. Compared with the present situation, these figures highlight a number of key assumptions, which governed previous investigations and their design proposals, for example: Earlier studies tended to overemphasise the traffic demand along the Buitengracht corridor, both in absolute and relative terms. Current figures indicate a 28% demand for this movement, compared with a 45% assumption in the first Buitengracht Traffic Study. Until the mid-1980s, none of the studies were able to anticipate the V & A Waterfront development, and the establishment of a Waterfront – Foreshore – Culemborg development axis. The earlier Freeway and Buitengracht studies were generally over-optimistic about the growth potential of the CBD and its attractiveness as a car-commuting destination. The 1984 Central City Traffic Study underestimated vehicular growth on the assumption that the present traffic constraints will encourage the use of public transport. All other studies have confirmed that the present 3-lane cross section of the outer viaducts would not have sufficient capacity to accommodate traffic growth beyond 2000. These observations clearly highlight the need for re-assessing the original scheme, and in particular, the need for the Buitengracht Freeway connection. Provided that the Buitengracht corridor remains a low bulk conservation area, there can be little justification for this costly and environmentally intrusive scheme, if one considers that the future Western Boulevard freeway connections will significantly reduce traffic flow along this route. During the morning commuter peaks, Buitengracht currently carries more than 2 800 veh/hr southbound between the Coen Steytler and Hans Strydom intersections. This is approximately 1000 vehicles per hour more than would be necessary to cope with the present unconstrained traffic demand, had the elevated Western Boulevard connections been in place. A number of recent traffic impact assessments have confirmed the pressing need for the completion of the elevated connecting links with Western Boulevard, both from a traffic demand and network connectivity point of view. Although present traffic demand is slightly less than for the proposed Buitengracht connection, this traffic 7 pattern involves a number of increasingly problematic right turn movements at critical intersections. It is therefore anticipated that the completed Western Boulevard ramps will also attract right turning traffic, which presently uses Coen Steytler Avenue/ Dock Road and Somerset Street towards destinations in the Waterfront and Sea Point. In view of the above, and in anticipation of further developments in the Green Point area, it will be safe to assume that the Western Boulevard connection could attract up to 30% of the total westbound morning peak hour traffic on the elevated freeway. This equals about 1 900 veh/hr, if applied to the present unconstrained traffic demand. Unfortunately, the present traffic demand figures (constrained and unconstrained) clearly indicate that additional capacity will be required on the elevated freeway section, and that route pre-selection is an absolute necessity for the implementation of the Western Boulevard links. This involves the completion of the inner viaducts, as originally envisaged. If however, the Buitengracht Freeway had to be deleted from the scheme, as suggested, then the inner viaducts could be reduced in cross section from four to two lanes per direction, which equals the terminating lane balance on the Western Boulevard ramps. The cost savings between this proposal and the original viaduct scheme could be between 30 and 50%. 4.4. Ultimate Traffic Profile From a capacity perspective, the reduced scheme (minus the Buitengracht connections) will still have considerable scope for the handling of future traffic growth. Schematically, this is shown in Figure 5. Figure 5: Foreshore Freeway - Ultimate (am) Peak Hour Traffic Profile (capacities shown in brackets) Western Boulevard 2550 (4200 – 2 lanes) 1800 5950 (6300 – 3 lanes) 4200 N1 750 1750 Coen Steytler – Buitengracht Intersection 6000 2500 Eastern Boulevard 1900 In terms of this proposal, the Foreshore Freeway will have enough spare capacity to accommodate a traffic growth scenario of 90% on the N1 corridor (from 3150 veh/hr to 6000 veh/hr). This is 50% more than the current unconstrained traffic demand along the N1, and should therefore provide adequate capacity for more than 15 years, depending upon the future land use developments in and around the CBD. Traffic growth on the Foreshore Freeway could however be retarded, by using the reserve lane capacity on the N1 and N2 approaches (due to the reduced cross section 8 of the central viaduct) for direct access ramps into a parking garage under the elevated freeway structures. The ultimate lane capacities in Figure 5 also provide a clear illustration that the future traffic demand of the CTICC and the other Foreshore developments can be met without significant problems. Results of the CTICC Transport Impact Assessment are listed in Table 1. 4.5. Weaving The primary purpose of a freeway preselection scheme is to minimise or eliminate weaving. For this reason, a weaving analysis of the original freeway alternatives played a very important part in the decision to select Scheme 3B as the preferred concept. This scheme had the lowest predicted weaving volumes, totalling 1455 vehicles per hour on the Inner Viaduct. However, in terms of current demand patterns, this scheme would have been at a distinct disadvantage, due to the wrong assumptions about the proportional split between the Buitengracht and Western Boulevard traffic. In other words, the highest demand pattern (and the one with the highest growth potential), which is the movement from the N1 to the Western Boulevard, is forced to weave across the Eastern Boulevard – Buitengracht traffic. Previously it was thought that this situation would be reversed. In terms of the reduced scheme, the weaving problem shifts from the inner to the existing outer viaducts, due to the merging of traffic from the Eastern Boulevard and N1 in order to reach the appropriate left- and right-turn lanes at the Coen Steytler intersection. Presently the Foreshore Freeway copes with weaving volumes of about 1 137, as shown in Figure 6. Figure 6: Weaving Profile on Outer Viaduct – Present Traffic (am peak hour) Dock Rd 1100 Buitengracht 2700 1200 407 1850 444 1443 693 2394 756 Eastern Boulevard N1 3150 Coen Steytler After the completion of the Internal Viaduct and its links with Sea Point, the total weave volume on the Outer Viaducts will reduce, to some extent, as a result of a shift in Waterfront traffic from Dock Road to the Western Boulevard. Overall, the weave situation will however benefit significantly from the large reduction in traffic on the through-movement along Buitengracht (from 2 700 to 1 430 veh/hr). 9 In terms of the ultimate demand (Figure 7), the total weave volume is expected to increase to about 1 940, which is nearly 33% higher than originally predicted for Scheme 3B, but still lower than any of the other scheme alternatives in the original freeway investigation. It should be noted however that a similar traffic demand profile would have generated a total weave volume of 2 362 vehicles in Scheme 3B. Figure 7: Weaving Profile on Outer Viaduct – Ultimate Demand with Completion of Inner Viaduct to Western Boulevard (am peak hour) Dock Rd 1822 Buitengracht 1900 2228 535 1750 655 1215 1287 2627 1573 Eastern Boulevard N1 4200 Coen Steytler 4.6. Intersection Analyses One possible area for concern is the future operation of the Buitengracht/ Coen Steytler intersection, which will ultimately come under severe pressure. This problem will mainly be as a result of heavy traffic flow on Coen Steytler/ Dock Road, and not so much from the through traffic along Buitengracht. At this stage it appears that the afternoon peak period right turns from the direction of the CTICC onto the freeway could become problematic. This was confirmed by a Traffic Assessment of the Foreshore Freeway (HHO, 1 June 2001) which found that the outbound Buitengracht ramp will be required to cope with medium-term unconstrained traffic flows. Further investigations are necessary, but the solution could also lie with the introduction of variable message signs (advanced redirecting of traffic), and the construction of parking structures under the freeway, to divert Convention and other Foreshore traffic away from the most critical intersections. 10 3 1 4 Western Boulevard 5 Foreshore Freeway N1 2 6 N2 Buitengracht Table 1: Foreshore Freeway – Observed and Predicted Peak Hour Traffic Flows (am westbound) Source Planning of Culemborg Viaduct, Table Bay and Buitengracht Freeways (1968) Buitengracht Traffic Study (1978) Addendum to Buitengracht Traffic Study (1978) Central City Traffic Study (1984) Highway Capacity Study (1991) CTICC Transport Impact Assessment (2001) CTICC Transport Impact Assessment (2001) Present Demand (constrained) Present Demand (unconstrained) Ultimate Flow Profile Target Year 1991 1 4709 (63) 2 2708 (37) 3* 7417 (100) 4 1533 (21) 5 2670 (36) 6 3214 (43) 2000 8233 (75) 5303 (67) 2589 (59) 2517 (61) 4792 (64) 4792 (69) 3150 (63) 4000 (63) 6000 (71) 2811 (25) 2591 (33) 1805 (41) 1576 (39) 2753 (36) 2190 (31) 1850 (37) 2200 (37) 2500 (29) 11044 (100) 7894 (100) 4394 (100) 4093 (100) 7545 (100) 6982 (100) 5000 (100) 6200 (100) 8500 (100) 785 (7) 2503 (32) 1018 (23) 683 (17) 2000 (27) 1856 (27) 1155 (24) 1426 (24) 2550 (30) 5343 (48) 2739 (35) N/a 4916 (45) 2652 (33) N/a 1868 (46) 3401 (45) 3137 (45) 2415 (48) 2976 (48) 4050 (48) 1542 (37) 2144 (28) 1989 (28) 1430 (28) 1798 (28) 1900 (22) 2000 2000 Observed 1990 Unconstrained 2010 Constrained 2010 Observed 2001 2001 2010 * Inner and outer viaduct figures combined, where applicable 11 9 7 10 Western Boulevard 11 Foreshore Freeway N1 8 12 N2 Buitengracht Table 2: Foreshore Freeway – Observed and Predicted Peak Hour Traffic Flows (am eastbound) Source Planning of Culemborg Viaduct, Table Bay and Buitengracht Freeways (1968) Buitengracht Traffic Study (1978) Addendum to Buitengracht Traffic Study (1978) Central City Traffic Study (1984) Highway Capacity Study (1991) CTICC Transport Impact Assessment (2001) CTICC Transport Impact Assessment (2001) Present Demand (unconstrained) Ultimate Flow Profile Target Year 7 8 9 10 11 12 2000 1714 (66) 1240 (37) 1547 (68) 1473 (61) 2696 (60) 2696 (60) 1900 (63) 866 (34) 2128 (63) 723 (32) 759 (39) 1828 (40) 1828 (40) 1100 (37) 2581 (100) 3369 (100) 2270 (100) 2432 (100) 4524 (100) 4524 (100) 3000 (100) 1066 (41) 1596 (47) 1197 (53) 1271 (52) 2333 (52) 2333 (52) 1800 (60) 1255 (49) 1605 (48) N/a 260 (10) 167 (5) N/a 214 (9) 955 (21) 955 (21) 340 (11) 947 (39) 1236 (27) 1236 (27) 860 (29) 2000 2000 Observed 1990 Unconstrained 2010 Constrained 2010 Observed 2001 2010 * Inner and outer viaduct figures combined, where applicable 12 4.7.Counterflow (eastbound) traffic Morning peak hour traffic from the CBD and the suburbs along the Atlantic Seaboard, has been increasing consistently since the initial completion of the Foreshore Freeway. Projections in Table 2 indicate that the traffic demand from these origins could, in ten years time, reach similar levels as the present westbound traffic (5 000 veh/hr) on the existing elevated freeway. About half of this traffic (2 300 veh/hr) will be coming from the Sea Point direction onto the future Inner Viaduct. Although it is expected that the (am) eastbound traffic volume on the Inner Viaduct will be greater than the (am) westbound flows, both will be well within the 4 200 vehicles per hour capacity limit of this facility. Serious traffic problems can however be expected if the Inner Viaducts and the connections with the Western Boulevard are not constructed in the immediate future. 4.8. Afternoon peak hour traffic (east and westbound) Afternoon peak period traffic is normally less pronounced than in the mornings, and it can therefore be assumed that a balanced road network will cope with the afternoon demand, if it has sufficient capacity for the morning peak periods. This is generally true for the Foreshore Freeway, except for the fact that the present up- and downstream traffic constraints do have a major impact on the operation of this facility. In the afternoons, for example, the Foreshore Freeway is regularly flooded by backup traffic, due to the bottlenecks at Koeberg Interchange and beyond. Eastbound capacity improvements on the Foreshore Freeway will therefore necessitate additional road capacity along the N1 corridor. 5. SCHEME PROPOSALS In view of current traffic patterns and the most recent transport impact assessments for the Foreshore area, it is proposed that the authorities formally adopt a revision of the original Foreshore Freeway Scheme to be implemented as soon as possible. This revised scheme, as shown in Figure 8, differs from the original concept in respect of the following: The southbound Buitengracht viaduct has been deleted in its entirety The original northbound Buitengracht viaduct has been deleted and replaced by a much reduced optional connection, from Riebeeck Street onwards The inner viaducts have been reduced in width from four lanes per direction, to a 2-lane cross section westbound, and a 3-lane cross section eastbound The section of the inner viaducts between Heerengracht and Oswald Pirow can be supported by load bearing parking structures instead of the original prestressed concrete design Options exist for direct freeway access into the supporting parking structures 13 Compared with the original scheme, it can be demonstrated that this proposal offers a far superior cost-benefit solution, with much improved environmental and urban design concepts. The revised scheme is also more appropriate in terms of current assessments of future travel demand. Figure 8: Foreshore Freeway - Revised Scheme Proposal 2 3 3 2 2 3 2 4 3 2 3 NOTES: 2 2 1. LANE CONFIGURATION SHOWN IN CIRCLES 2. STAGE 1 STAGE 2 3. ACCESS TO PARKING GARAGE Acceptance of the proposal to modify the Buitengracht connections should however be subject to the following conditions: Stringent limits on all future land use developments and parking provision along the Buitengracht corridor Improved links between De Waal/ Mill Street and Buitengracht to promote this as an alternative CBD access and bypass route Improved public transport into and within the Inner City to reduce future growth in car commuting An investigation to determine the feasibility of parking structures under the inner viaducts with direct freeway access, to divert traffic from entering the CBD Retaining the option to use the Coen Steytler parking garage entrance lanes as an alternative access into the Canal Precinct The introduction of variable message signs and real-time CCTV equipment on all Inner City freeway approaches to monitor and regulate traffic flow and route choice. The option of providing revenue generating parking structures below the future freeways should receive serious consideration. Preliminary investigations have confirmed that a 3-level parking structure, similar to the Coen Steytler garage, is possible and that this could accommodate up to 2 400 parking bays. A scheme of this nature could act as a replacement for the planned central viaducts as originally envisaged. Another modification to the original scheme could be the introduction of grade separation at the Table Bay Boulevard/ Oswald Pirow intersection. From a traffic perspective, the westbound elevated links towards Sea Point are considered to be prerequisites for further CBD development (including the V & A) 14 and for the successful operation of the Convention Centre. Currently, the Coen Steytler/ Buitengracht intersection is already operating at over-saturated traffic flow conditions. 6. COST ESTIMATES The most recent cost estimates for the completion of the Foreshore Freeway were obtained from VKE Consulting Engineers on 14 June 2001. These figures, as shown in Table 3, were prepared for the revised Foreshore Freeway Scheme, with and without the parking garage option. Figure 9: Construction Elements for Costing Purposes 3 Western Boulevard Coen Steytler Parking Garage Par kin g 4 1 CTICC Ga rag eO 5 2 ptio n 8 iro w F. M ala n 7 N1 Os wa ld P D. He e re ng rac ht 6 Eastern Boulevard Table 3: Preliminary Cost Estimates for the Revised Foreshore Freeway Scheme Element No. 1 Section Eastbound ramp from Sea Point 2 Westbound ramp to Sea Point 3 Central viaducts between Coen Steytler parking garage and Heerengracht, above CTICC Eastbound Central viaducts between Coen Steytler parking garage and Heerengracht, above CTICC Westbound Elevated viaduct between Heerengracht and N1/ Eastern Boulevard freeways - Eastbound Elevated viaduct between Heerengracht and N1/ Eastern Boulevard freeways Westbound 4 5&7 6&8 Description Length 2x3,7m lanes 2x2m shoulders 2x3,7m lanes 2x2m shoulders 272m Cost Estimate (R million) 23,0m 360m 31,0m 3x3,7m lanes 2x2m shoulders 334m 42,3m 2x3,7m lanes 2x2m shoulders 321m 30,2m 3x3,7m lanes 2x2m shoulders 846m 91,1m 2x3,7m lanes 2x2m shoulders 784m 65,1m TOTAL (without parking garage) 15 R 282,7m Construction elements 5 to 8 could be replaced by a three-level (2 500 bay) parking garage with access ramps to the N1 and Eastern Boulevard Freeways. The cost of such a structure will increase the overall cost of the freeway scheme by about R 170 million. In view of the longer-term need for additional parking along the Foreshore, it is estimated that this revenue earning facility could become self-financing and an ideal opportunity for a public/ private partnership arrangement. If, for whatever reasons, the parking garage option does not prove to be viable, then the scheme could be implemented in phases, with the following budgeting requirements: Table 4: Budgeting Proposals for implementing the Revised Foreshore Freeway Scheme Construction Element 3 & 4 - Central viaducts between Coen Steytler parking garage and Heerengracht, above CTICC 2 - Westbound ramp to Sea Point 6 & 8 - Elevated viaduct between Heerengracht and N1/ Eastern Boulevard freeways - Westbound 1 - Eastbound ramp to Sea Point 5 & 7 - Elevated viaduct between Heerengracht and N1/ Eastern Boulevard freeways - Eastbound Project Management City of Cape Town: TOTALS PAWC: TOTALS Financial Year 2002/03 2003/04 R 27,1m 2001/02 R 46,4m R 1,6 2004+ R 29,4m R 65,1m R 1,5 R 21,5m R 91,1m R 0,5m R 50,0m R 0,8m R 40,0m R 38,8m R 1,0m R 30,0m R 62,1m R 0,7m R23,5m R 42,3m It should be noted that the original Foreshore Freeway Scheme, with its four-lane cross section, would have cost at least R90m more, excluding the cost of the Buitengracht links which would have added an additional R 80 m. Author: W. W. CROUS 16