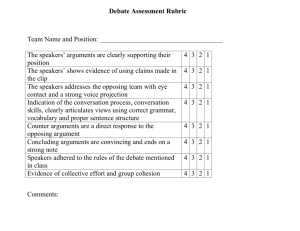

Cognition Through a Social Network: The Propagation of Induced

advertisement