Document 10446250

advertisement

il.iT.

LIBRARIES. OEVWgVj

^'

working paper

department

of economics

TAX INCENTIVES AND THE DECISION

TO PURCHASE HEALTH INSURANCE:

EVIDENCE FROM THE SELF-EMPLOYED

Jonathan Gruber

James Poterba

94-10

Feb.

1994

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

Cambridge, mass.02T39

TAX INCENTIVES AND THE DECISION

TO PURCHASE HEALTH INSURANCE:

EVIDENCE FROM THE SELF-EMPLOYED

Jonathan Gniber

James Poterba

94-10

Feb.

1994

M.I.T.

JUL

LIBRARIES

1 2 1994

RECEIVED

TAX INCENTIVES AND THE DECISION TO PURCHASE HEALTH INSURANCE:

EVIDENCE FROM THE SELF-EMPLOYED*

Jonathan Gruber and James Poterba

MIT

and

NBER

July 1993

Revised February 1994

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 introduced a new

tax subsidy for health insurance purchases

by the self-employed. We analyze the changing patterns of insurance demand before and after tax

reform to generate new estimates of how the after-tax price of insurance affects the discrete choice

of whether to buy insurance. We employ both traditional regression models and difference- indifference methods that compare changes in insurance coverage across groups around TRA86. The

results from our most carefully controlled comparison suggest that a one percent increase in the cost

of insurance coverage reduces the probability that a self-employed single person will be insured by

1.8 percentage points.

*We

are grateful to

Gary Engelhardt, Martin

Feldstein, Victor Fuchs, Austan Goolsbee, Jerry

Hausman, Lawrence Katz, Brigitte Madrian, Thomas McGuire, Joseph Newhouse, Douglas Staiger,

John Shoven, Glenn Sueyoshi, Mark Wolfson, Richard Zeckhauser, two annonymous referees, and

many seminar participants for helpful suggestions, to Todd Sinai and Aaron Yelowitz for expert

assistance with the TAXSIM and SIPP tabulations, respectively, and to the Center for Advanced

Study in Behavioral Sciences, the National Science Foundation, and the James Phillips Fund for

research support.

The value of employer-provided

taxable income.

This

is

health Insurance benefits

is

not included in an individual's

one of the most costly federal tax expenditures, accounting for an estimated

revenue loss of nearly $50 billion

in

1993.

The

resulting tax

forms of compensation, which may induce "overinsurance,"

and rising medical expenditures

United States.

in the

is

wedge between insurance and

often viewed as contributing to high

Several recent proposals therefore call for

capping the dollar value of health insurance benefits that can be excluded from taxation.

with the objective of lowering the

other

number of uninsured persons, propose extending

Others,

the tax incentive

for health insurance to encourage insurance purchase.

The

insurance.

substantial

effect of these proposals

If this elasticity is small,

depends

critically

on the price

elasticity

then limiting the tax expenditure on health insurance

amounts of revenue but not have much

effect

on

level

If the elasticity is large,

may

raise

the extent of health insurance coverage,

and proposals to expand insurance tax credits will have small effects

uninsured individuals.

of demand for health

in

reducing the number of

however, tax policy will have large effects on the

of insurance coverage, but capping the employer deduction will raise less revenue.'

Because

it is

difficult to find

exogenous sources of variation

in

insurance prices, there

convincing empirical evidence on the price elasticity of demand for health insurance.

Variation

either through time or in a cross-section of households or firms reflects differences in the

for health care as well as in the costs of providing this care.^

There are few shocks

is little

demand

to the supply

side of the health insurance market that are not potentially correlated with shocks to insurance

demand and

potentially

studies

[1982],

rates

that

exogenous source of variation

have

Tax changes provide a

can therefore identify the insurance demand curve.

tried to exploit this source

Vroman and Anderson

change over time.

The

in the after-tax price

of price variation. The

of health insurance.

first,

types of

exemplified by Long and Scott

[1984], and Turner [1987], examines

fact, for

Two

how

coverage changes as tax

example, that health insurance coverage has fallen

in die

2

1980s, as individual marginal tax rates have fallen,

This correlation

to insure.

of

may be

employment

to service sector

taken as evidence that taxes affect the decision

spurious, however, because other factors that affect the extent

may have been changing

insurance coverage

healtii

is

employment during

as well.

A

large shift

from

industrial

the 1980s, rising real health care costs, and the

widening income distribution may also have affected the demand for health insurance coverage.

Another approach

to estimating the effect

of taxes on coverage

is

to analyze a single cross-

section of individuals or firms, and to ask whether those with higher tax-related subsidies to

insurance purchase are

more

likely to

be covered by health insurance or to spend more on insurance

Studies of this second type include Taylor and Wilensky [1983],

coverage.

Holmer [1984], and Sloan and Adameche

First, differences in tax rates in

[1986].

Woodbury

[1983],

These studies face three important problems.

a cross-section arise

in part

from differences

in the

underlying

behavior of individuals or firms, such as through labor supply, family structure, or the nature of the

workforce.

It is

difficult to tell

whether differences

or these behavioral differences.

Second, there

marginal tax rate for the wage-fringe decision

at

is

in

observed insurance coverage are due to taxes

a basic problem in measuring the appropriate

a firm.

Since the workers

face a range of different marginal tax rates, the wage-fringe choice

problem.

rule, in

Finally,

It is

a single firm typically

a standard collective choice

impossible to escape arbitrary assumptions, such as imposition of a "median worker"

measuring the change

we

is

at

shall

in the

marginal tax rate that determines the wage-fringe mix

at a firm.

argue below that many of these studies mis-specify the after-tax price of health

insurance.'

One

notable line of research that avoids the problems with cross-section or time-series

variation in after-tax insurance prices

and Phelps [1987] and Thorpe

et al.

is

the "experimental" approach, used for example by Marquis

[1992].

Marquis and Phelps use evidence from the

RAND

3

Health Insurance Experiment to estimate a price elasticity of

Thorpe

of -0.6.

et al. estimated

were offered a generous subsidy

an elasticity

in the

demand

for supplementary insurance

range of -0.07 to -0.33 for small businesses that

to the price of health insurance.

It is

not clear, however, whether

such experimental evidence generalizes to evaluating the design of broad-based tax policies towards

health insurance.*

In this paper,

we

exploit a

new source of tax-induced

variation in the effective price of health

insurance: the 1986 change in the tax treatment of insurance purchases by self-employed individuals.

Prior to the

Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86), self-employed

income tax deductions paid for

individuals

who

their health insurance with after-tax dollars.

did not itemize their

After

could claim a tax deduction equal to 25 percent of their health insurance costs.

effects of this tax-induced price

TRA86,

We

they

examine the

change on the demand for health insurance by self-employed

workers.

Our methodology avoids many of

comparing the change

other changes in the

in

the confounding factors described above.

coverage for the self-employed

economy

that

may have

so that they

become a

demand

by looking

firms.

A

at

the self-employed,

self-employed person

We

may be

we

is

can control for

show

that the

by the employed changed very

little

around

natural candidate to pick

variation that

we

by

We

comparing similar self-employed individuals before and

sources of

of the employed,

affected health insurance coverage.

tax incentives for the purchase of health insurance

TRA86,

to that

First,

correlated with

up other economy-wide trends. Second, by

after the tax reform,

we

can control for other

income or self-employment

status.

Finally,

avoid the problem of identifying "marginal" employees in large

a firm's only employee.*

use the Current Population Survey (CPS), a nationally representative survey of over

50,000 households

that collects information each

March on

the respondent's insurance status in the

4

Because the

previous year.

CPS

does not collect data on insurance expenditures, our analysis

focuses on the price-sensitivity of the discrete decision to purchase insurance.

parameter that

is

central for evaluating proposals to use

expanded tax incentives

This

is

precisely the

to increase insurance

coverage among currently uninsured individuals.

Our

study

is

divided into six sections.

The

first

provides a detailed description of

how

the

tax code affects the incentive to purchase insurance, with particular attention to the 1986 change in

the after-tax price of health insurance for both the

employed and self-employed. Section

II

outlines

our modelling framework. The third section describes our data and discusses the insurance demand

In Section IV,

of the self-employed.

we

construct a measure of the after-tax price of health

insurance, and report probit models of insurance

workers.

the

These models

demand

parallel those that

demand

have been used

for both self-employed and

previous studies of

in

how

employed

taxes affect

for fringe benefits, and our results confirm previous findings that changes in the after-tax

price of insurance significantly affect insurance purchase decisions.

Section

V explores this

finding in

more

detail

by comparing the changes

in insurance- demand

over the 1985-1989 period between employed and self-employed individuals, as well as the changes

in

insurance coverage of high- and low-income self-employed and employed groups.

In nearly

all

cases, these comparisons support the earlier finding that tax-induced reductions in the price of

insurance raises the

demand

for insurance.

A

brief concluding section

summarizes and

interprets our

findings, and suggests several directions for future work.

I.

The

Tax

Incentives and the Relative Price of Insurance

tax system subsidizes expenditures

on health care

the analysis of the tax incentive for insurance purchase.

in several

ways, thereby complicating

Individuals with employer-provided health

5

insurance are not required to include the value of this insurance

the self-employed did not receive any comparable tax benefit

who

if

in their

taxable income.

Until 1986,

they purchased insurance. Taxpayers

claim itemized deductions can also deduct from their taxable income the portion of their

expenditures on medical care and directly-purchased health insurance which exceed a certain fraction

of their income from their taxable income.

insurance premia does not in

one alternative

itself

to insurance, direct

Thus, the tax deductibility of employer-provided health

imply that the tax system subsidies insurance purchases because

payment of medical expenses,

is

tax system that allowed equal deductions for both health insurance

would provide no

net subsidy to health insurance , although

it

also a deductible expense.

A

premia and medical expenses

would provide a

substantial subsidy

to health care expenditures.

To model

random medical

the tax incentive for insurance purchase,

costs with an expected value that

independent of whether the individual

insurance which costs

of-pocket.

If the tax

(1 -l-X),

code

where X

insured.*

is

is

that

an individual faces

normalize to unity, and that these costs are

The

between purchasing

individual chooses

the policy's load factor, and paying for medical costs out-

premia and medical expenditures symmetrically, then the

treats insurance

cost of insurance relative to the direct outlays

benchmark case against which we evaluate

1.1.

we

we assume

on medical care

is

q^^

=

the after-tax price of insurance in

I

-I-

X.

This

more complex

is

the

cases.

Employed Taxpayers

We

begin by analyzing the incentives for insurance purchase by an employed taxpayer

can purchase health insurance through his employer.

[1992].

There are three ways for

this

exposition builds on the analysis by Phelps

taxpayer to pay for medical care: with employer-provided

insurance, with insurance purchased on

individual as the marginal

Our

who

own

worker who decides whether

his

employer

We

view

this

will offer insurance,

and

account, or with "self-insurance."

6

that both

assume for simplicity

employer-provided and directly-purchased insurance policies have no

deductible and a zero coinsurance rate.

We

focus on the average cost of insurance, and the average

cost of self-insurance, rather than the marginal cost of an additional dollar of insurance expenditure

because the data

We

we

analyze apply to the discrete choice of whedier or not to purchase insurance.

denote marginal tax rate on earned income by

t,

the employer share of the payroll tax by t„,

and the loading factor on employer-provided health insurance by \;

we assume

that payroll taxes

are borne in full by labor.

Employer-provided insurance

strictly

dominates insurance purchased on

own

account for both

itemizing and non-itemizing taxpayers, due to the higher loading factors on individual policies, the

full deductibility

own

of employer-provided insurance expenditures relative to the partial deductibility of

insurance expenditures, and the deductibility of employer-provided health insurance from the

payroll tax as well as the income tax.

provided insurance and self-insurance.

the employee's

wage

is

reduced by

(1

We

When

payment

The employee's

as well.

the

employer purchases insurance

+Xg)/(1-I-Tj.

one dollar of benefits or paying wages of

tax

therefore focus on the comparison between employer-

1/(1

The employer

after-tax

wage

where a

taxable income.^

outlays

(1)

is

(1-l-Xg),

between purchasing

therefore falls by [(l-T-T„)/(l-l-T„)]*(l-l-Xg).

an employed taxpayer does not buy insurance

are (l-ar),

indifferent

of

-HtJ, since each dollar of wages requires a payroll

This expression measures the after-tax cost of insurance

If

is

at a cost

in

terms of foregone wage income.

at all, his

expected after-tax medical costs

indicates the expected fraction of medical expenses that will be deducted

The

after-tax price of

employer-provided insurance relative

from

to direct medical

therefore

cu'

=

{(l+Xg)(l-T-Tj]/[(l-KTj(l-ar)].

Insurance load factors raise the price of insurance relative to self-insurance,

in part offsetting the tax

-

7

incentive to purchase insurance.

to

The

greater the fraction of medical expenses that a taxpayer expects

be able to deduct, the higher the relative price of insurance.

We

change

define the tax-induced distortion in the relative price of insurance as the percentage

in the price

= (cu'-O/cu =

e

(2)

where

qin,

=

1

who

taxpayer

of insurance as a result of the tax code:

+ \-

To

(l-T-Tj/[(l+Tj(l-aT)]-l

illustrate the

magnitude of

consider a non-itemizing

this distortion,

faces a federal marginal tax rate of 28 percent, a state tax rate net of federal

deductibility of 5 percent (so t

=

0.33), t„

=

0.0765, and assume that

itemize, a quarter of medical expenses will ultimately be deductible

In this case, 6

-

..

=

if

the taxpayer does not

from taxable income (a

=

.25).

-0.399, so the tax code effectively reduces the price of insurance by forty percent.

For the employed taxpayer, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 had two countervailing effects on

the after-tax price of insurance.

First,

it

lowered marginal tax rates substantially; the top rate on

earned income dropped from 50 percent to 28 percent.

Second,

TRA86 made

it

more

difficult to

claim medical deductions, raising the non-deductible level of medical expenses from 5 percent to 7.5

percent of

AGI and

taxable income

if

increasing the standard deduction, the

The

that a taxpayer can deduct

they decide not to itemize, from $3760 to $5000.

returns claiming itemized medical deductions

reform.

amount

net effect of

TRA86 on

fell

from

In fact, the percent of tax

from 10.3% before TRA86,

to

4.5%

after the

the price of insuring, relative to self-insuring, therefore

depends on the particular circumstances of the employer taxpayer.

1.2

Self-Employed Taxpayers

Now

price of

1

consider a self-employed taxpayer

H-Xj,

who buys

insurance in the individual market, at a

and deducts part of his health insurance cost

taxpayers, the after-tax cost of purchasing insurance before

(/3)

as an itemized deduction.

TRA86 was

For these

(\-Pt){1+\^, where

/3

=

8

[(1+Xi)

-

F]/(1+Xi)

is

the tax -deductible share of insurance costs.

"floor"

amount of spending on

become

deductible.

quarter of the

After

health costs that the taxpayer

TRA86,

the after-tax cost

The parameter F denotes

must incur before medical expenses

became (l-max03,.25)*T)(l+Xi), because one-

premium could be deducted, but taxpayers could now only

itemize the fraction of their

insurance expenditures which were not taken as part of the general tax subsidy.

self-employed taxpayers, the after-tax price of health insurance changed from qj^'

TRA86,

ar) before

to qi„'

=

(l-max(/3,.25)*T)(l-l-X)/(l-aT) afterwards.

insurance purchase by this group was altered by the

for itemizing medical expenses (through

self-employed taxpayers with

>

a and

;3),

25%

For these itemizing

=

The

(1-/3t)(1 -I-X)/(1-

tax incentive for

tax subsidy, the changes in the thresholds

and changes

.25 both before and after

in

marginal tax rates.

TRA86,

Note

-

Calculating the After-Tax Price of Health Insurance

To

estimate a, the expected fraction of medical expenses that a self-insured person will be

able to deduct

we

that, for

the health insurance deduction

for the self-employed did not affect the tax subsidy to insurance.

1.3

the

from

his taxes,

and

/3,

the expected fraction of insurance costs that will be deductible,

use data on the distribution of expenditures on both health care and privately-purchased insurance

from the 1977 National Medical Care Expenditure Survey.

We

combine

this

information with data

from the Treasury Department's Individual Tax Model, along with the NBER's

to estimate the

more

expected after-tax price of health insurance.

Appendix

A

TAXSIM

program,

describes our algorithm in

detail.

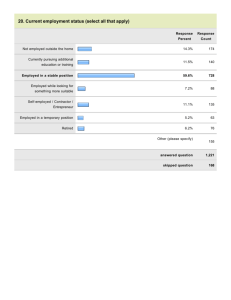

Our

estimates demonstrate that the 1986

self-employed individuals, but had

insurance. Table

I

presents

little

effect

Tax Reform Act subsidized insurance purchase by

on the incentive

summary information on

to self-insurance, for several years

surrounding

for

employed persons

to

purchase

the average after-tax price of insurance, relative

TRA86. The

data are stratified into employed and

9

self-employed, and also into groups based on household taxable income.

the self-employed, the average after-tax price of health insurance

employed individuals there was a

trivial decline.

income self-employed individuals.

of $50,000

price

fell

in

to those with real

from 1.455

There was

little

Our

the

$1985

We

The

illustrate this

fell

The

results

from 1.41

tax price reduction

show

that for

to 1.33, while for

was most dramatic

by contrasting persons with incomes

for high

in

excess

incomes below $20,000. For the high income group, the tax

to 1.307, while the fall for the

low income self-employed was much smaller.

change for either high or low income employed persons.

finding of virtually no change in the relative price of insurance and self-insurance for

employed contrasts with the usual conclusion, presented

Hamermesh

for

example

in

Woodbury and

[1992], that falling marginal tax rates raised the cost of health insurance.

TRA86

raised

both the after-tax cost of employer-provided health insurance and the cost of self-insuring for medical

expenses.

While the tax change therefore raised the cost of purchasing health care, with or without

insurance,

it

the total

had

little

effect

on the incentive

amount of health care purchased, the

to insure.

If

one were studying

crucial relative price

would be

a weighted average of the insured and self-insured costs, relative to

all

how TRA86

affected

that for health services,

other goods.

TRA86

raised

this relative price.

2.

We

begin our study of

Modelling the

TRA86

Demand

for Insurance

and insurance demand by specifying a discrete choice model

of individual insurance demand, which follows previous studies such as Marquis and Phelps [1987].

We

assume

that an individual's underlying

demand

for health insurance,

Ij',

can be described by a

vector of socio-demographic characteristics Xj, income Yj, and after-tax price of health insurance.

10

(3)

li'

V

In practice,

0,

and

I;

=

=

is

Probdi

where F

Y^a

is

distribution,

=

+

Pi7

we

1)

will

=

+

We

unobservable.

otherwise.

probability that

(4)

+

Xi^

Ci.

observe instead a

The insurance purchase

>

0)

=

>

Prob(€i

is

-Xfi

the cumulative distribution function for

and estimate the parameters

in (3)

by

variable, defined

decision exhibits a

observe insurance coverage

Probdi*

dummy

by

I;

=

1

if

I;*

random component, and

>

the

^

-

Yja

ej.

fitting

-

Pi7)

We

=

-

1

assume

F(-Xii8

that

e;

Y,ct- ?r(),

-

follows a normal

a probit model to a pooled set of Current

Population Survey data, including observations from before and after the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

This probit equation combines

Some of

insurance.

this variation,

many

different sources of variation in the price of health

particularly the cross-sectional variation in after-tax prices

between households, will be correlated with other household

for health insurance.

to biased estimates

may

affect the

of the price

elasticity

An example

of insurance demand.

tax code, a large

number of children

household's marginal tax rate conditional on pre-tax income, since

it

may

also

demand more

health insurance for other reasons.

can

in a family

illustrate this

lowers

increases the

personal exemptions that can be claimed on the household's federal tax return.

family

demand

Omitting these unobserved attributes from the estimating equation could lead

With a progressive

problem.

attributes that

the

number of

However, a

large

This source of cross-sectional

variation in the after-tax cost of health insurance and the probability of purchasing health insurance

could therefore yield an apparently positive relationship between tax price and demand.

While one

can try to control for such effects, there always remains a danger of spurious correlation.*

We

can describe the three sources of identifying variation

(i)

(ii)

Cross Section: Employed

Cross Seaion: High-

\s.

vs.

in

our pooled

CPS

data sample:

Self-Empbyed Workers, Each Year;

Low-Marginal Tax Rate Workers, Each Year;

11

(Hi)

Each

is

Time Series: Before

vs.

After

TRA86

prone to yield spurious conclusions about the price

specifications

where the

tax rate

is

of insurance demand

elasticity

in

the only source of variation in the after-tax price of insurance.

For example, the cross-sectional differences between employed and self-employed workers could

easily be driven

to

by unobserved differences

in the tastes for risk

become self-employed. Cross-sectional

differences in marginal tax rates within the

self-employed groups are largely the result of differences

household decisions that

is

potentially

may be

Combining these

strategy.'

shifts in

insurance

not decide

employed and

income, family status, or other

demand over

different sources of variation offers a

The time

this

series variation alone

time period.

more promising

identification

For example, while there may be a number of reasons why self-employed persons have

a lower insurance coverage rate than

in relative

in

correlated with tastes for insurance.

confounded by other

who do and do

of workers

employed persons

in a cross-section,

coverage rates across these groups from before to after

differences fixed.

by examining the change

TRA86, we can hold

these other

Similarly, by comparing high marginal tax rate self-employed persons to low-

marginal tax rate self-employed persons both before and after the subsidy

for cross-sectional differences in attributes that

may be

is

in place,

we

correlated with the tax rate.

can control

This

is

the

essence of our modelling strategies below.

3.

Insurance Coverage Information

in the

Current Population Survey

Each March, the Current Population Survey (CPS) asks respondents about

insurance coverage in the previous year.

characteristics,

March CPSs

and income

to create a

in the

The CPS

includes information on

previous year as well.

their health

employment

We combine data from the

sample of individuals for the pre-tax reform period, and

status,

job

1986 and 1987

we combine

the

12

respondents in the

the

March 1989 and 1990 CPSs

March 1988 CPS, which

year for tax rules.

on insurance

collected data

The pre-TRA sample

We

reform sample.

to construct a post-tax

status in 1987,

because

therefore provides information

was a

this

exclude

transition

on insurance coverage

in

1985-1986, while the post-reform sample applies to 1988-1989.

The major advantage of the CPS

for our purposes

information on health insurance status.

collects

is

that

it is

the largest annual survey that

This large sample size

may be

important for

examining groups, such as the self-employed, that constitute a small fraction of the population. The

principal disadvantage of the

expenditures.

CPS

that

is

Another disadvantage

it

that the

is

does not include information on health insurance

CPS

questionnaire

was changed

in

March, 1988,

in

order to more accurately capture the insurance coverage of dependents. Previous surveys asked each

household

in the

member over

fifteen years old if

household was covered by

this policy.

he had insurance

in his

member was asked

own name and who

else

it

if

covered.

from outside the household, previously

own name, and

in

he was covered by insurance, and

if so,

This change meant that dependents

labelled uninsured,

25-54, since this

by the

CPS

coverage

is

We

minimize

were now recorded

problem

in

an individual's

The change

own name,

Instead,

we

else's.

This could affect our results

also implies that

we

is

in their

own

in

whether

March

it

was

who had coverage

as insured.

may be changing

the least likely to be affected

are unable to examine insurance

since the survey responses are not consistent over time.

focus on coverage from private health insurance either in one's

if

else

our analysis by focusing on persons aged

the group which the Census Bureau [1988] notes

questionnaire change.'"

in

this

who

so,

thehousehold. Beginning

This survey change implies that insurance coverage rates of dependents

spuriously over this time.

if

For household members without insurance

name, coverage was imputed based on the responses of others

1988, each household

in his

there

were changes

in

own name

or in someone

insurance coverage from the self-

13

employed's other family members, particularly

below,

we

Table

In the results

II

own names."

presents the characteristics of our sample. Individuals are classified as self-employed

they report themselves to be self-employed based on their main job

least

TRA86.

therefore examine single and married individuals separately, since most insured single

individuals have coverage in their

if

their spouse, coincident with

$2000 ($1985)

in

self-employment income.

The

last

year and

latter restriction is

if

they report at

used because the health

insurance deduction was limited to the amount of self-employment income earned by the individual.

Thus,

we

exclude persons with only occasional self-employment earnings from our sample.

Employed persons are those who report themselves

earnings, and also earn at least

$2000

in

wages and

to

be employed, report no self-employment

salaries.

Relative to the employed, the self-employed are slightly

is

more educated and older (experience

defined as age minus education minus 6), are less likely to be female or black, are roughly equally

wealthy, and are less likely to be in sales or manufacturing.

There

is

employed sample over time. For the self-employed, there

characteristics of the

little

is

change

an increase

in

the

in the

percentage that are female and in average family income, but other characteristics appear similar over

this

time period.

The working uninsured resemble

terms of demographic characteristics, but

are

more

in

the

employed more than the self-employed

in

terms of occupational and industrial distribution they

similar to the self-employed.

Table

III

presents background information on the incidence of insurance coverage for both

employed and self-employed workers before and

marital status, to provide

and by tax

filing unit

and any dependents

some information on

income. Tax

who

after

TRA86.'^ The sample

is

disaggregated by

the potential confounding effects of spousal coverage,

filing units are

defined in the

are younger than 19 or are students.

CPS

as heads of families, spouses,

14

Table

III illustrates five

among self-employed persons

all

is

government

groups

is

quite low;

it

income.

more

pre-TRA86

rapidly with income for

facts

is

of private insurance coverage

69.4% before TRA86, and

only

is

50%

for

Second, the probability of insurance coverage for

Third, the rate of insurance coverage for employed persons

higher than that of self-employed persons at

rises

averages

tax subsidies for health insurance.

rises sharply with

First, the rate

This suggests the potential for a large response of the self-employed

single self-employed persons.

to

important phenomena.

all

except the lowest income levels. Fourth, coverage

employed persons than for self-employed persons. This

consistent with the presence of a tax subsidy to the

employed

that

set

of

becomes more

valuable as incomes and tax rates rise.

The

finding in Table

fifth

III is

a increase

in die rate

of insurance coverage among

employed workers between the pre-TRA86 and post-TRA86 periods, and a coincident decline

rate

of coverage for employed workers.

single and married individuals, and for

change

in relative

in the

evident for the disaggregated groups of

is

most of the disaggregated income categories as well." This

insurance coverage rates for employed and self-employed workers around the Tax

Reform Act of 1986 does not

reflect a long-term pattern

of shifting insurance coverage during the

Table FV shows CPS-based insurance coverage rates for employed and self-employed

1980s.

individuals for the 1982-1990 period.

workers

in the

The coverage

rates for single

1982-1986 period show downward trends.

evident trend in the coverage rate

for the

This pattern

self-

among

employed and self-employed

For the whole population, there

the self-employed, and

weak evidence of a

is

no

declining trend

employed.

4.

Table

V

Estimates of Insurance

Demand Equations

presents estimates of probit models such as specification (4) above.

The models

15

relate insurance

coverage to income and the after-tax price of insurance. Each equation controls for

a detailed set of individual and job characteristics: potential experience; education; indicator variables

(< 35 hours/week of work),

for gender, marital status, and non-white; controls for part time

than half-time

(<

18 hours/week), and part-year

log of tax unit income;

self-employment

(< 26 weeks of work

in the

four year dummies;

status;

less

preceding year); the

and 15 major industry

dummies.'"

The

first

column presents the estimates from a regression

Column two shows

is

higher

among white

the self-employed are

tax subsidy to

and

is

much

than non-white workers, and

be covered.

less likely to

after-tax price

TRA86)

higher for

likely to

full

time than less-than-

have insurance coverage, and

These two findings may be the

of insurance

is

or less valuable (after

result

of marginal probabilities

is

TRA86)

of the

when

not presented here.

the tax price

The

is

added

rises

for the self-employed.

included in the equation reported in column (3).

majority of the control variables do not change

set

is

employer provided health insurance, which becomes more valuable as income

either non-existent (before

The

results are broadly consistent

Insurance coverage rises with experience, education, and

Higher income families are much more

time workers.

fiill

The

the marginal effects of each coefficient.'^

with prior studies of insurance coverage.

marriage,

that excludes the tax cost variable.

Since the

to the regression, the

ftill

tax price has a highly significant coefficient,

suggesting that higher after-tax prices reduce insurance coverage.

We

interpret our coefficient

estimates by calculating the derivative of the probability of insurance coverage with respect to the

after-tax price

-0.3.

A

more

of insurance. The implied derivative

natural parameter

tax price of insurance,

would change by

if

ie.

the

is

in die third

column of Table 4

is

approximately

the semi-elasticity of insurance coverage with respect to the after-

number of percentage

points that the insured fraction of the population

the after-tax price of insurance rose by

one percent.

To compute

this

semi-

16

elasticity

multiply the estimated derivative by 0.96, v^ich

we

potential

approximately the average after-tax

This yields a semi-elasticity of -0.252."

price of insurance in our data.

One

is

problem with

this specification is that the tax cost

second-order income effect, since the tax price

itself

may simply be

depends on income

capturing a

We

way.

in a nonlinear

attempted to control for this by replacing the log of family income with an exhaustive set of indicator

$1000 income bracket.

variables for households in each

entire

is

sample and the self-employed only

consistent with the fact that the

in the tax price

set

fiill

fell slightly,

The estimated

and remained sizeable and significant.

it

is

than the log of tax filing unit income.

more problematic

partly reflects the

demands of

We

observe in the CPS.

employed workers

occupation

cell.'^

for

rate

may be

The

a collection of workers at a firm, not just the individual

results in

column four replace the

The estimated

This rise in the price effect

relevant marginal tax price for the

arise either the collective choice

tax

rate.

workers

this

argument

group

worker

we

tax price for

in their industry

and

employed workers with

this

derivative of coverage with respect to the price of insurance

may be

is

now

-0.425.

the result of a reduction in the error with which the

employed

is

measured.

Measurement error

in the tax price

can

problem discussed above, or from errors induced by our imputation

If

this

measurement error

averages

to

zero

industry/occupation group, then the grouped regressions will be free of such error.

develops

this

therefore construct an alternative measure of the after-tax price for

approximately doubles and the implied semi-elasticity

individual's

appropriate for the self-

employed persons, since insurance coverage for

as the average value of the after-tax price for

"grouped" tax price.

of the

This

of dummies explains only 2.5 percent more of the variation

While measuring tax price using the individual's tax

employed,

coefficients for both the

in the context

of labor supply.

in

a

broad

Angrist [1991]

17

5.

The

Demand

"Differences in Differences" Estimates of Price Effects on Insurance

estimates above suggest that the after tax price of insurance affects the probability that

how

Yet they do not provide any direct evidence on

a household will purchase insurance.

households responded to the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

The empirical

tests in this

seaion focus on

the effects of particular sources of variation in the after-tax price of health insurance.

5.1

Employed

The

vs.

first

Self-Emoloved Workers. Pre- and Post-TRA86

source of variation that can be used to identify the price elasticity

among self-employed

insurance coverage

when TRA86 took

that for

effect.

We

is

the change in

persons, relative to employed persons, over the period

noted above that the tax price for self-employed workers

employed workers was unchanged

as a result of

TRA86.

We

increase in the insurance coverage rate of self-employed as opposed to

fell,

while

would therefore expect an

employed workers coincident

with the tax reform.

There are many reasons why self-employed individuals may have lower insurance rates than

employed persons, one of which

is

studying the difference in insurance coverage rates for this group over time, however,

for any time invariant factors in their insurance

difference to the change in insurance coverage

demand.

Furthermore,

among employed

we

in-differences" estimate that can be labelled the effect of the taxes

statistics

Each

cell

can control

this

time

individuals, to control for time series

TRA86.

assumption that there are no non-tax shocks to only one of these groups, the result

Table VI presents summary

we

can compare

trends in economy-wide insurance demand, including the income effects of

controlling for any other factors.

By

the lack of a tax subsidy for health insurance before 1986.

is

Under

the

a "differences-

on insurance demand.'*

on insurance demand for these groups, without

contains the private insurance coverage rate

group labelled on the axes, and the standard errors are shown

in parentheses.

The

first

among

the

row of Table

18

4%

6 shows that insurance coverage for the self-employed rose by

same time, coverage

the

time period.

rise in the

employed, despite a lack of change

This suggests that other economy-wide trends led to lower

incentives.

this

significantly for the

fell

between 1985-6 and 1988-9. At

There

is

for insurance over

Using the experience of the employed as a control for these trends,

TRA86

coverage of the self-employed of 6.8% during the

consistent with

demand

TRA86

raising insurance purchase

by the self-employed

in their tax

we

find a net

enactment period.

relative to the

This

is

employed.

a potential problem with this identification strategy: the composition of the employed

and self-employed groups may have been changing over time. Devine [1992] reports that there was

an increase in CPS-based self-employment rates beginning around 1986; our analysis confirms

this." If the

new self-employed

individuals had a higher propensity to be insured than the previous

self-employed, then compositional changes could contribute to rising insurance rates. However, even

if

the

new self-employed were

as likely to be insured as the average

compositional shift can explain only about

and self-employed workers that

shifts

10%

of the relative

we observe. We also evaluated

by comparing the self-employed before and

CPS

the self-employed in the

after the

after

employed worker, the

shift in

insurance rates for employed

the importance of such compositional

TRA86. The observable

Tax Reform Act are

resulting

characteristics of

quite similar to those of the

group

we

observe before the Act.^°

To

in

ftirther control for the possibility that the differences in

Table VI are due to changes

between 1985-6 and 1988-9,

these characteristics.

(5)

Ij*

SELF;

is

=

We

Xi/3 -H Yitt

set equal to

also estimate probit

of the self-employed or employed groups

models for insurance demand

that control for

begin with an equation of the form:

-I-

one

we

in the characteristics

insurance probabilities reported

SELFi.6,

if

+

the worker

POST86i*62

is

+

SELFi*POST86i*63

self-employed, and

is

-I-

e,.

zero otherwise.

POST86i

is

set to

19

one for years

after 1986,

and

is

zero previously.

framework, POST86i and SELF; control

In this

for the general time series trend in insurance coverage and the secular

employed, respectively.

The

interaction,

TRA86.

The estimate of

insurance coverage rate for self-employed workers changed

employed workers.

controlling

for

individual

Even

covariates

there

if

effect of being self-

POST86i*SELFi, captures the change

self-employed, relative to the employed, after

rate for

demand

were no

more

relative

after

in

demand

6, indicates

for the

whether the

1986 than did the coverage

changes in group characteristics,

can reduce the sampling variance of the differences-in-

differences estimator.

Table VII reports only the coefficients of

coefficients

interest,

such as

on the other included explanatory variables are similar

63,

from equation

to those in

Table

The

(5).

5.

The

top

panel of Table VII presents the results of estimating equation (5) for the entire data sample as well

as for single

and married individuals separately.

We

present the probit coefficients and their

associated standard errors, the marginal effect of the interaction on the probability of insurance

coverage, and the implied estimate of the derivative of

demand with

respect to the tax price.

Derivatives are calculated using the probit marginal effects from this regression in the numerator,

and the difference-in-difference of the average tax cost for each

figures can be converted to semi-elasticities

cell in the

These

denominator.

by multiplying by 1.37, the average

after-tax price

of

health insurance for self-employed individuals in our sample.^'

The

results in the first panel of

Table VII confirm the conclusions from

difference-in-difference estimate of the effect of the tax subsidy

The magnitude

is

is

in

Table

5.

The

sizable and statistically significant.

about three-fifths of the estimate from Table 6, implying a price derivative of -0.5,

and a semi-elasticity of -0.685.

This finding

is

similar to the result

from the probit equations

in

Table 5, for the case when the after-tax price for employed individuals was measured using group

20

average marginal tax rates.

The second and

and married workers separately.

much weaker

thus

may

We

for the married group,

columns of Table 7 present estimates for single

third

distinguish these groups because the

who may be

TRA86

is

large and statistically significant for both groups,

for single persons,

which

is

While the estimated

approximately

it is

40%

larger

consistent with this interpretation.^

Although our analysis

surrounding

is

covered by their spouse's health insurance, and

not be responding to the incentives put in place by the law change.^

price elasticity

experiment

relies primarily

TRA86, we have

on CPS data

to assess

changes

in insurance

coverage

also explored the robustness of our findings using the Survey of

Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

The SIPP

is

a nationally representative longitudinal

survey which follows respondents for 28-32 months, and collects information on both labor force

attachment and health insurance.

Its

most important

virtue,

on health insurance coverage did not change during

difficulty with the

CPS.

Its

this

from our perspective,

time period, so that

primary disadvantage, however,

is

that

we

is

that the question

can surmount

sample sizes are much smaller

than those in the CPS, so that the precision of our estimated insurance coverage rates

use information from the fourth

which collected point

The changes

in

wave of the 1984 survey and

the seventh

in insurance

lower.

We

wave of the 1986 survey,

coverage that result from comparing the 1985 and 1988 SIPP data

In 1985,

we

estimate that 82.4 percent of the self employed

were covered by insurance, with a standard error of 10.3 percent.

is

is

time information on insurance coverage for spring 1985 and 1988.

support our CPS-based conclusions.

coverage rate

this

For employed, the insurance

89.3 percent (0.3). In the 1988 data, 85.3 percent (15.8) of self-employed workers

reported insurance coverage, compared with

89.0 percent (0.4) of employed workers.

difference-in-difference estimator for the change in insurance coverage

is

therefore

The

3.2% (1.6%).

21

Low-Income Self-Emoloved Workers.

5.2 High-Income versus

A

second component of insurance price variation

is

Pre- and

Post-TRA86

due to different marginal tax rates within

the self-employed group.

The post-1986 deduction should be more valuable

employed individuals than

to lower

the former group

is

higher.

We

i;

(6)

HIINC

is

=

The

XiP

+

test the effect

basic specification

YiO

set equal to

-I-

of

TRA86 on

HIINCi*6,

+

POST86i*62

-I-

time for self-employed

this

now

tests

in real family

income."

us to control for both time series trends in

demand among

and low income self-employed that

that the earlier finding

of a relative rise

the effect of the tax reform

income, and zero for

coefficient

may

status, then this

this

on the

framework allows

the self-employed,

affect their

coverage for the self-employed

market for insurance by employment

€-,.

whether insurance coverage rose more among the

characteristics of high

in

+

The estimated

high-income self-employed than their lower-income counterparts. Once again,

in the

rate for

of self-employed

different groups

HIINCi*POST86i*63

one for individuals with over $50,000

interaction term, 63,

self-

is:

individuals with less than $20,000 in real family

HIINC*POST86

income

income self-employed individuals, since the marginal tax

workers by estimating another differences-in-differences probit model,

workers only.

to higher

demand.

is

an

and for fixed

To

artifact

the extent

of a change

model provides an independent

test

of

on insurance demand.

The second panel of Table VII

presents the results of estimating equation (6).

We again

find

a statistically significant effect of the tax subsidy, and the implied price derivative of demand, -0.37,

is

similar to that of the previous case.

smaller for the married self-employed.

It is

The

much

larger for single self-employed workers, and

larger magnitude of the estimated price effect for the

single self-employed in this specification than in the first differences-in-differences specification

be a function of differential take-up rates for the health insurance deduction.

Tax

return data

may

from

22

1989 suggest that the probability of claiming the health insurance deduction rose with income, which

will impart

an upward bias to the estimated price effect

estimation.

The

5.3 High versus

true price effect lies

Low Income

somewhere

in

in

our second differences-in-differences

between the two estimates.^

Low Income Employed.

Self-Emploved. versus High versus

Pre/Post-

TRA86

The previous

difference-in-difference regression

factors causing insurance

income

class.

This

demand changes by income

may be an

is

identified

by the assumption

class are not correlated with tax changes

documented changing opportunities between the

A

rich and poor.

demand changes by income

class

Murphy

[1992], have

natural test for whether non-tax

pose a problem

is

to

compare our

difference-in-difference estimates for the self-employed to similar estimates for the employed.

estimate that

employed

TRA86

should have had

relative to the

the income scale

Therefore,

if

is

little

low-income employed, since the decline

fall in

TRA86,

in

marginal tax rates

at the

top of

the tax subsidy to self-insuring for that group.

to find a relative rise for high-income

suggest that factors other than

We

impact on the health insurance demand of the high-income

compensated for by the

we were

by

untenable assumption given the nearly linear relationship between tax

changes and income in an era when several researchers, for example Katz and

factors affecting insurance

that non-tax

employed workers as well,

it

such as an economy-wide shock to insurance demand

would

at

high

incomes, might explain our findings for the self-employed group.

In fact, Table III

showed

well as the self-employed.

positive estimates of 63,

that insurance

coverage rates rise with income for the employed as

Furthermore, regressions similar to

which appears

to

be driven by a drop

(5) for the

in

employed

yield significant

insurance coverage at low incomes

rather than a rise at high incomes, as for the self-employed.

To

assess the implications of this finding for our results,

we

can

move

to a "differences-in-

23

differences-in-differences" framework, as in

the

employed

is

viewed as a control for economy-wide trends

income and low-income self-employed was larger than

employed persons.

We do

that for

i;

=

+

Xi/3

-I-

As

demand by high- and low-income

Yitt

corresponding income groups

-

-I-

HIINCi*6,

HIINCi*SELFi*65

in the earlier specifications, this

-I-

+

POST86i*62

+

HIINCi*POST86i*63

SELFi*POST86i*66

-I-

+

SELFi*84

HIINCi*POST86i*SELFi*67

model includes controls for the secular demand

The second

level interactions control for

changes

employed SELF*POST86), and differences

in

the effect

TRA86

The bottom panel of Table VII

estimates are reduced by about

estimate of 67

0.334.

When

statistically

is

(relative to the

(relative to before

TRA86);

that

remains to identify the effect of

low-income) self-employed (relative to

this is the

term HIINC*POST86*SELF.

reports estimates of equation (7).

50 percent

among

the high-income self-employed

the subsidy

the employed) after

for insurance

demand among

low-income self-employed (HIINC*SELF). All

on the high-income

demand

for the self-employed relative

relative to the

is

demand

Cj.

demand

high vs. low income groups (HIINC*POST86), changes in

to the

in the

-I-

effects of being

self-employed (SELF) or high income (HIINC), and for general time series trends in

(POST86).

among

so by estimating the following probit model for the entire employed and

self-employed sample:

(7)

in

class for

therefore ask whether the difference in the rate of coverage growth between high-

One can

persons.

Gruber [1994], where the change by income

relative to earlier estimates.

The

price derivative

For the entire sample, the

negative but only significant at the 10 percent level; the implied semi-elasticity

this

model

is

estimated on the sample of single persons, however, the results are

significant and the point estimate

is

negative, with an implied price derivative of

insurance purchase of about -1.3 and a semi-elasticity of -1.78.

persons, the group that

is -

we view

as yielding a

For the sub-sample of married

weaker "experiment" because of the presence of

24

spousal coverage, the estimated effect

These

is

negative but statistically insignificantly different from zero.

results suggest that, for the full

sample of workers, the economy-wide trend towards

increased insurance coverage for higher income classes

However, for

differences tests used above.

may weaken the second of our differences-in-

single workers, the

whom

group for

our experiment

is

most well defined, there remains strong evidence of a response to the tax subsidy.

6.

Conclusions

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 extended a

costs to self-employed workers, bringing

provided health insurance.

employed with

demand

that of

We

focuses on insurance

them closer

compare the change

employed workers and

for insurance coverage.

partial

The

results

income tax deduction for health insurance

to the tax treatment afforded to

in health insurance

employer-

coverage for the

self-

find strong support for a negative price elasticity

of

from our most carefully controlled comparison, which

demand among unmarried

individuals, suggest that a

one percent increase

in

the cost of insurance coverage reduces the probability that a self-employed household will be insured

by 1.8 percentage points.

While the precise estimates of the

elasticity are

somewhat dependent on

other aspects of the econometric specification, the general direction of our findings

to

is

very robust

our choice of specification.

One

potential limitation of our analysis

characteristics

is

our relatively small

set

of control variables for

of the employed and self-employed that might affect their demand for health

insurance. If the distributions of the unobserved characteristics of these groups remain constant over

time, the presence of unobservables should not contaminate our findings.

to health insurance for the self

health insurance

demand

to

If the

TRA86

tax subsidy

employed induced some previously employed workers with high

become

self

employed, or

if

other aspects of TRA86 or coincident shocks

25

altered the characteristics of the self-employed in a systematic

way,

this

could affect our results.

have not found any evidence, however, to suggest the importance of such contaminating

A

to

second limitation of our analysis

is

by our data

set,

implies that our estimates

subsidies to increase coverage

among

factors.

our focus on the discrete decision of whether or not

This focus, which was

purchase insurance, rather than the quantity of insurance to purchase.

dictated

We

may be more

relevant for the design of tax

the uninsured than for the evaluation of limits on the tax

deductibility of employer-provided health insurance.

Future research could usefully extend the type

of methodology explored here to estimate the price elasticity of the quantity of insurance demanded,

in

order to answer questions such as

individuals will change

if

how

the level of insurance

demand amongst

the tax code allows partial deductibility of health insurance outlays.

Furthermore, discrete decisions such as whether or not to become insured

to "recognition effects."

individuals

may

When

a

new

policy, like

TRA86,

demand among

itself,

and not

its

the self-employed.

an effort to disentangle steady state demand

magnitude, which was key

It

would be

elasticities

may be

susceptible

provides an incentive for insurance,

evaluate their insurance status and decide to buy insurance.

the presence of the subsidy

insurance

currently insured

fruitful to

in

Thus,

it

may have been

driving the increase in

extend this line of research

from such "recognition

effects".

in

26

APPENDIX

CALCULATING THE AFTER-TAX PRICE OF INSURANCE

A:

This appendix describes our calculation of the after-tax price of insurance coverage for each

person

in the

CPS. The GPS reports data on

filing units : these units

own

filing their

may be

smaller than families,

We used the

returns.

and households, but not on tax

individuals, families,

if

the family unit includes individuals

For each of these tax

not married and no children; joint

if

are

simple rule that individuals are considered part of a tax filing

filing units,

we

who

younger than 19 or

is

extracted data on: filing status (single

if

unit if they are the head of the family, the spouse, or a dependent

enrolled in school.

who

married; head of household

if

is

unmarried with children); number

of dependents; wage and salary income; dividend and interest income; self-employment income; farm

income; and other income.

We

TAXSIM

then computed marginal tax rates for each of our tax filing units using the

calculator.

individual tax returns.

takes as input

The CPS data

all

are missing a

most notably itemized deductions and

tax returns,

Individual

TAXSIM

Tax Model data

unit's probabilities

file,

number of important items

capital gains.

which contains over 70,000 tax

of itemizing and declaring

capital gains conditional

of the detailed information that

We

is

NBER's

reported on

that are reported

on

therefore used the Treasury

filing units, to

capital gains, as well as the

impute each tax

filing

amounts of deductions and

on having them.

Our imputation algorithm employed Treasury Tax Mode!

data for 1986 and 1988.

We

applied data for these years to 1985 and 1989 by inflating or deflating monetary amounts using the

Consumer

to

Price Index.

one of 64

joint, with

income

>

We

classifications:

imputed information to individuals by assigning each

16 income classifications, by two

head of household

and schedule

C

in the former),

income

<

=0).

CPS

observation

filing status classifications (single

and

by two self-employment classifications (schedule

In each classification,

we

C

assigned individuals the

27

average amount of itemized deductions and capital gains income reported by taxpayers in that

classification with non-zero

We

amounts.

also assigned the average probabilities of itemizing

deductions and realizing capital gains for each classification.

for each tax filing unit, corresponding to: (1)

capital gains; (3)

we

No

No

itemization,

no coital gains;

is

The

tax rate

a weighted average of these four rates, where the weights are the

imputed probabilities of itemizing or declaring capital gains

after-tax price

no

(2) Itemization,

itemization, coital gains; and (4) Itemization and capital gains.

use in our regressions

The

We then imputed four possible tax rates

in

each classification.

of health insurance must account for the relative tax treatment of health

insurance and out-of-pocket expenditures on health care.

We

compute the average tax price using

the following formulas for the self-employed and employed:

Pc.

=

I

Pp

-

o/(\+0)]*(\-B'T)

ar

= (Gm*\(\+\)*(\-T-T^y(i+T^)] + (i-Gm*rn+v*i/(i-HO) +

1

where

+

l(l-^X:)*I/a-^0)

X,

-

o/n-KO)i*(i-7T)

ar

and X^ are the loading factors on individual and group health insurance, respectively,

out-of-pocket spending on insurance,

O

is

out-of-pocket spending on health care services,

employer spending on group health insurance,

T

is

total

I is

G

is

insurance spending and health care services

spending, and /3',a,7 are parameters that depend on the tax system and the distribution of health care

spending,

a

is

defined

in the text, (3'

equals max(/3,0.25) for years after

TRA86, and 7

is

defined

below.

The numerator of each

insurance.

A

self-employed person pays the individual insurance loading factor on the portion of

her health care spending that

expenditures.

price formula reflects the tax adjusted price of purchasing health

is

on insurance, but no loading factor on out-of-pocket medical

The average self-employed person can expect

that a fraction

/3'

of her expenditures

28

will either lie

on insurance and health care services

subject to the

initial

25%

above the threshold for tax itemization, or be

Thus, the net cost of their medical spending

tax subsidy.

is

only

(1-/3't)

of the

dollar outlay.

For the employed person, the calculation

expenditures

made on

his behalf (G) are

spending, the after-tax price

is

fiilly

is

complicated by the fact that the employer's

tax deduaible.

Thus, for the fraction

only (1-t-tJ/(1-I-tJ per dollar of spending.

G/T of

health

The remainder of

expenditures consist of his expendimres on health insurance and out-of-pocket medical services.

assume

that

he can purchase insurance

at the

same group loading

his

We

factor (X,) and that his insurance

expenditures are not tax deductible. The average employed person with employer-provided insurance

expects that a fraction

7

of his

own

spending on insurance and health services will

lie

above the

itemization threshold.

The denominators of Pse and Pe

on

self- insurance,

reflect the cost

of

self- insuring.

There

is

no loading factor

and the costs of medical care are reduced by a, the fraction of those costs that the

taxpayer expects to be able to itemize.

The key parameters

The

first

for estimating the after-tax price of insurance are

\, \,

/3,

7, and a.

two parameters can be estimated using data on group and individual insurance premiums

and claims experience, from

HIAA

(1991).

The

last three

parameters represent the expected fraction

of insurance and medical spending that can be itemized by the self-employed insured, the employed

insured, and the self-insured, respectively.

We

estimate them by assuming that the average person

choosing between these categories expects to itemize the same fraction of expenditures as those

currently in each category.

We

then estimate these fractions using information on the distribution

of medical and insurance spending from the 1977 National Medical Care Expenditure Survey

(NMCES),

inflated to

1986 and 1988

levels using the medical care CPI.

We

then divide the

29

NMCES

into three

subsamples of families: those

in

which both the head and the spouse are

uninsured; those in which both the head and spouse have non-employer provided health insurance;

and those

group

is

in

which

either the head or the spouse has employer-provided health insurance.

Each

then further divided into three income categories and four categories of family structure.^*

For each subgroup, we calculate the amount of

their

spending that can be claimed as an

itemized deduction as:

DED =

where f

is

is

max[I

-I-

the fraction of

family income,

I is

O

-

f*Y

-

SD*PI,

AGI which

0]

medical expenditures must exceed

spending on insurance for those

denotes own-spending on medical care,

probability of itemization in the subgroup.

the standard deduction,

is

SD

is

The

who

in

order to be itemized,

own

purchase insurance on

the standard deduction, and PI

final

component of

account,

Y

O

the average

is

sum, the exp)ected value of

this

an approximation to the loss of the standard deduction

in

excess of the

taxpayer's other itemized deductions.

The

AGI

fraction of medical spending that

floor that such spending

reforms such as

must exceed

TRA86, which

raised the

in

is

itemized depends on the level of such spending, the

order to be itemized, and the standard deduction.

AGI

floor

from

5%

to

7.5% and

deduction, reduce the share of health care outlays that can be itemized.

Tax

increased the standard

This affects the after-tax

price of health insurance.

Finally, for each

by the

total

spending

subgroup

in the

in

each year,

subgroup.

we

estimate total deductible spending and divide this

This yields our estimates of

/3

(from the purchasers of non

employer-provided health insurance), 7 (from the employer-insured), and

For 1988,

we

reflect the

25%

increase the numerator in the calculation of