Document 10446249

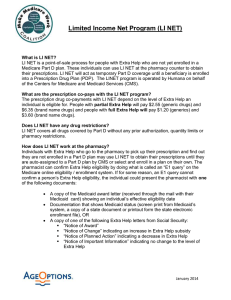

advertisement