Document 10444717

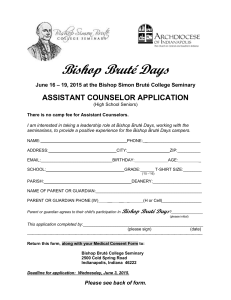

advertisement