Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Navigating the Challenges

advertisement

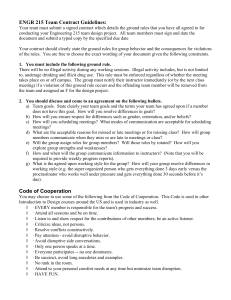

Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Navigating the Challenges of Family Caregiving Exercise • Take a piece of paper • Divide it into 3 equal columns • First column: Write in the words, “Paid Caregiver” • Second column: Write in the words, “Me” • Third column: Write in the name of your loved one receiving care Exercise, continued • Under the first column, write in some of the challenges you have with the paid caregivers. These challenges can include having a stranger in your home; not knowing how to handle problems such as chronic lateness; or issues about the caregiver’s relationship with your family member Exercise, continued • Under the third column, write in some of the challenges you have with your family member. These may include disruptive behavior; physical strain of care; or issues with medication Exercise, continued • Under the second column, write in some of the challenges that you face caring for yourself. These may include not having enough time; feeling pulled in too many directions; or guilt about taking a vacation What we hope to achieve: • After attending this session, we want you to be able to: – Negotiate boundaries with paid caregivers – Communicate effectively with paid caregivers – Increase repertoire of caregiving skills specific to family members with cognitive impairments – Increase repertoire of skills to care for yourself and prevent burnout Some Challenges Associated with Paid Caregiver • Stranger(s) in my home • Persons of different socioeconomic or ethnic strata – Can lead to different interpretations of “on time,” of “care,” of “involved,” of “place in the family” • Hierarchy of the home care agency Boundary Issues • Is the PCA a friend or employee? – How do I discuss problem behaviors without jeopardizing relationships? • Vulnerability of elder – Elder gets involved with personal issues of PCA • My own feelings – Jealousy, inadequacy; is the PCA closer to my family member than I am? Care Needs • Is the care recipient really getting what he or she needs? • Is the quality of care and the commitment by the PCA satisfactory? – If these needs are not being met, how do you communicate them to the PCA? How do you communicate your concerns to the agency? The Triad: You, the PCA, and Your Family Member • You may sometimes feel like the middle of a seesaw as you balance the needs of your family member on the one side and the responsibility of working with a paid caregiver and the agency on the other • Good communication skills can help you address problems and issues without inadvertently creating more Why are we talking about communication? • Challenge to communicate with loved ones who have dementia or are ill • Challenge to have strangers come into your home and care for your loved ones • Differences between you and the PCAs can cause communication difficulties – Different ethnicities, socioeconomic strata Communication • We think we are communicating, but are we? – We may be sending unintended messages, either nonverbally or extraverbally • Opposite-speak • Sarcasm – Sometimes, we are sending intended messages, but cloaked in pointed humor (this way, we can deny it if the interaction becomes uncomfortable • We think we heard the message, but did we interpret it correctly? Giving respect - names are important • Call people what they want to be called: If her name is Mary Jones, do you call her Mary, Ms. Mary, Miss Mary, Mrs. Mary, Ms. Jones, Miss Jones, Mrs. Jones? • Be clear about how YOU want to be addressed and how you want your family member to be addressed Communicating with Clarity and Respect • Avoid “opposite speak.” Opposite speak is when one uses sarcasm by saying the opposite of one’s true feelings in an attempt to express one’s true feelings. (e.g., I really enjoy being spat on by people, it just makes my day!) If what you really mean is that you don’t like being spat on then just say, “I don’t like to be spat on.” Communicating with Clarity and Respect • Communication is a two way event • Listening is an active event • Listening actively is one way to demonstrate respect. Communicating with Clarity and Respect • Listening actively requires letting the speaker know that s/he was heard and understood. • Listening actively requires direct eye contact, sometimes standing or sitting still, verbal and non verbal gestures, sometimes writing a note about what is being said, taking turns, not interrupting. Respect is listening • • • • • • Listen actively Look, stop, wait - let them finish Don’t interrupt Turn off radio, TV - completely off Let them know you heard and understood Paraphrase Communicating with Clarity and Respect • Listening actively let’s the speaker know s/he is worth listening to. • When speaking to older individuals assess the level at which you must project, don’t assume everyone has hearing loss and therefore presume to shout at them. Communicating with Clarity and Respect • When speaking to older people be certain that side noises (e.g., TV, radio, traffic noise, other people speaking at the same time) do not interfere with the person’s hearing. Sometimes with older people their ears will hear background noise just as loudly as they hear the person sitting right in front of them. Communicating with Clarity and Respect • Address older individuals with respect in tone and language. • Use language of their day, not the most hip new slang. • Assertive language is plain and clear – and respectful of feelings Communicating with Clarity and Respect • Assertive language does not suggest or imply – it is direct but is respectful of feelings. • Assertive - say what is on your mind, but keep in mind the feelings of others. • Aggressive - say what is on your mind, but don’t care about the feelings of others or deliberate try to hurt or offend them Communicating with Clarity and Respect • Respectful tones and words are as important during conflict as during harmony. • Use gestures if necessary to aid in communication. Addressing Unsatisfactory Performance First, make sure to review the contract between you and the agency If your family member is not receiving the care he or she is supposed to be receiving, address it in an assertive manner Keep voice neutral, try to keep emotion out of the interaction The Other Part of the Triangle: the Care Recipient • We talked about ways to communicate respectfully to the PCAs and agency employees as you negotiate and advocate for your family member • These same principles help when faced with the difficult task of caring for a loved one who may not always be cooperative Cognitive Impairment • Diminished “brain power” as a result of temporary or permanent physical changes in the brain or body • Can be from dementia (Alzheimer’s AIDS) • Can be a result of severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia Common Behaviors in Persons with Cognitive Impairment Non-aggressive • Moaning, repetitious words or sentences • Wandering, rocking Aggressive • Yelling, cursing, screaming • Hitting, spitting, biting • Paranoia is not uncommon, especially when the person with CI is trying to make sense out of the environment or situation. Sexual Behavior • Sexual behavior, such as masturbating in public is also not uncommon. • Sexuality is present in aging and disabled persons, and the confused person is often seeking sexual solace. Sexual Behavior • Persons with CI may confuse another person for a spouse or may forget they were ever married. • Inhibitions are removed, which explains why sexually inappropriate behavior may occur in public. Disruptive Behavior as a method of communication • All behaviors, no matter how distasteful, are the result of your family members’ response to some emotion or fear. Disruptive Behavior as a method of communication • Your family members with CI have difficulty interpreting stimuli and may react with violence if they believe that they are being harmed. • It is important to realize that the person with CI does not exhibit disruptive behavior because they choose to, but the behavior is the result of the dementia—communication patterns are altered by the disease causing the dementia Disruptive Behavior as a method of communication • Disruptive behaviors can be the result of your family member’s inability to tolerate noises, activities, or changes in the environment. • They have a reduced ability to filter out unimportant stimuli, so they are bombarded with everything equally. Assessing reasons for disruptive behavior • Misinterpretation of surroundings – Persons with CI have limited capacity for learning new information. – Even though they are told several times, “this is the bathroom,” they may still misinterpret the surroundings and may react with fear – Vision and hearing impairment may further create problems with correct interpretation Assessing reasons for disruptive behavior • Pain and painful procedures • May be aggravated by your family members who are resistant to taking medication and may not receive their pain or psychiatric medications Assessing reasons for disruptive behavior • Stress • Sensory overload • Meaningless noise Assessing reasons for disruptive behavior • • • • • • Desire for immediate attention Loss of control/autonomy Fatigue Desire for sexual intimacy Change in routine Psychiatric co-morbidities Strategies for coping with disruptive behavior • Determine antecedents to the disruptive behavior Strategies for coping with disruptive behavior • Bathing is a usual antecedent. • If water is near the face or head of a confused person, he or she may react in an aggressive manner – May need to avoid tub baths, use baby wipes or warm damp washcloths for different body parts Strategies for coping with disruptive behavior • Have your family member control the flow of water (e.g., using a hand-held shower head to direct the flow of water) • Let your family member get into the tub slowly • Approach your family member in a relaxed manner Strategies for coping with disruptive behavior • Less likely to provoke agitation. If one approaches a confused person in an authoritarian or “bossy” manner, your family member may react in an unfavorable way. • Avoid being focused solely on the task • Sometimes, your family member does not understand what is expected of him or her with a specific task, and may become frustrated and act out. Strategies for coping with disruptive behavior • It is a good idea to talk to your family member about personal things of interest to him or her during tasks (e.g., grandchildren, previous occupation, favorite activities) • Be flexible in approach with your family member • The use of gestures and pantomime to show your family member what you want him or her is helpful Strategies for coping with disruptive behavior • Do not limit your conversation to your family member because of the confusion. • “Chatting away” with your family member has been shown to improve agitated behavior. • Your family member may respond to the verbal stimulation. Strategies for coping with disruptive behavior • However, when asking your family member to do something, use short, onestep REQUESTS, not commands. • Do not keep repeating the same request, otherwise your family member may become agitated • Show interest in your family member, both verbally and nonverbally Avoid interruptions • Studies have shown that interruptions resulted in increased agitation and tension on the part of your family member and decreased flexibility and personal contact on the part of the nursing assistant. • Stay off of the telephone while doing care More Strategies • Remember not to take aggression personally, unless you have deliberately done something to provoke your family member, it is not your fault! • Praise your family member in an adult-like manner. • Have manipulatives in the environment More Strategies • In the home environment, have items available that are associated with activities that your family member previously enjoyed. • One family kept jumbo blunt knitting needles and bits of yarn in a basket for their grandmother, who was an avid knitter prior to the dementia. She derived comfort from sitting and holding the items in her lap. More Strategies • Use touch judiciously Some your family members respond well to touch; others may react negatively. • Find what works with your family members. More Strategies • If your family member is already agitated, touching in a forceful manner may escalate the agitation • Remove your family member from the area, if possible • If your family member is engaging in sexually inappropriate behavior (e.g., masturbating in public), will need redirection. More Strategies • Distraction • Humor or playful responses may divert your family member’s attention from the discomforting situation and may stop the aggressive behavior Promote decision making • Give your family member as much REALISTIC choices as possible, within their abilities • Helps your family members retain personal power and dignity Promote decision making • Shows that you care • Have your family member do as much care as possible • Explain to your family members that doing as much for themselves keeps their bodies working properly (e.g., finger strength, hand coordination) Promote decision making • Encourage your family member to use adaptors • Sometimes it is faster and easier to do it yourself, but you are not helping your family member in the long run • Make sure the environment is best suited for the needs of your family member Promote decision making • Does your family member like all of the stuffed animals on his or her bed, or did someone else place them there because he/she likes them? • Does your family member really need the 12 crocheted afghans on her lap or on his bed? Questions or Comments? Group Work • Think about a difficult situation involving the care of your loved one • When you communicated your concerns, was the situation resolved in a positive way? – What worked? What didn’t work? – Based on what you have learned so far, what could you have done differently? “It’s Like Losing a Piece of My Heart:” Dealing with Loss, Death, & Mourning Loss • Part of life • Can be sudden (death of a young person) or expected (death of a terminally ill person) Loss • Can be bittersweet – Transition of a child from infant, to toddler, to preschool, to school age – Loss of a child leaving home, but going to college and growing up Loss • Some losses seem bad initially, but then turn out to be a blessing (a man is laid off from one job, only to find a better one) Loss • When losses are ‘bunched’ together, as in older years, multiple effects can be devastating – Examples of losses in older years • • • • • • Death of spouse, family, friends Loss of home Loss of employment Loss of activities Loss of roles (caretaker, leader) Loss of own abilities – Memory – Functioning – Independence Reactions to Loss • Because losses are personal, reactions to loss are individualized – What may be a small loss to me may be a larger loss to someone else – The process of grieving is called “bereavement” Reactions to Loss • Although the process is individualized, there are some general components – Sadness • The person is unhappy with the loss. He or she expresses sadness, cries – Denial • “This isn’t happening.” “If I ignore it, I won’t have to deal with it” Reactions to Loss • Anger – Can be at self or others – May belittle others, may become a “difficult” or “demanding” family member – Sometimes, one family member is a target because he or she is “safe;” Mom may be angry at her out-ofstate son but vents her anger on her nearby daughter because Mom is afraid her son will never visit again. – May express anger by trying to exert control over those items that the person still has control over Reactions to Loss – Blaming • May seek to make someone else the culprit for the loss. This is an attempt to make meaning out of a loss • May blame self or others: “if only I had taken my medicine, I wouldn’t have had this stroke,” or “If only I had a better doctor, I wouldn’t have needed that amputation.” Reactions to Loss – Bargaining • “If I can learn to walk with this walker, you will let me go back to my apartment, right” • Can be with family, health care providers, even God Reactions to Loss – Depression • The person may lose interest in food, enjoyable activities • May sleep all of the time or most of the day • May cry easily and all of the time Reactions to Loss – Acceptance • Reconciles the loss with overall picture of self • Adjusts self-concept to “fill up” hole left by loss Reactions to Loss • This process may take days to years, depending on the extent and importance of the loss – Some people move out of one stage, only to return to it later – Some stay “stuck” in stages Caregiving Strategies • Avoid even more losses – Give your family member as much independence as possible – Give family members choices regarding meal ideas, daily activities – make choice options realistic – Listen to family members’ ideas about the care Caregiving Strategies – Do not take things personally • This is also extremely difficult • No one likes to be the scapegoat, but realize that your family member is not striking out at you, the person • Tell your family member, gently but firmly, “I don’t like it when you (fill in blank). I understand that you are upset and hurting, and I would like to help you” Death and Dying • You will be working through your own emotions as your loved one goes through the dying process – Can be prolonged or sudden, no way to predict • The PCA will most likely be working through his or her own emotions, too • What level of intimacy are you going to allow? What level of intimacy would you find reasonable or acceptable? Avoiding Burnout:Caring for Others by Caring for Ourselves Basic Needs • Food and drink • Sleep • Leisure Activities • Activity • “I don’t have time” Nutrition • Carbohydrates • Proteins • Fats Food Pyramid • High carbohydrate, low fat • Works for some people • High jumps in insulin, followed by blood sugar drops • In many people, causes carbohydrate cravings • Become hungry a few hours after the meal, want more Other Options • High protein, low carbohydrates (e.g. Atkins) • May be problematic • Works by putting body in a state known as ketoacidosis • People lose weight, but raise triglyceride levels and are more prone to heart disease, high blood pressure Healthier Options • “Zone Diet” or “South Beach Diet” • Eat protein at every meal – Low fat sources: tuna, chicken, cottage cheese, egg whites • Balance with “healthy” carbohydrates: fruit, vegetables “Healthier Options • Avoid white bread, white pasta (refined foods); Eat whole grain breads • The trick is that the food digests slowly, so that insulin levels remain constant • Eat small amounts of fat with meals Healthier Options • Read the labels • “Lowfat” and “nonfat” may have even more calories than the actual “real” foods • More sugars added to replace the fat; May do more harm than good Exercise • 2 types –Aerobic • Walking, running, swimming, bicycling • Cardiovascular benefits Anaerobic • Lifting weights • Weight lifting builds muscle so that you can burn more calories while resting • You cannot turn fat into muscle! Anaerobic • Muscle does not weigh more than fat, but it is denser!! • Think of exercise as “recess” or “playtime” • Helpful to involve friends, children • Helpful to combine both Sleep • Necessity, not a luxury • 8 hours/24 hours • Sleep hygiene – Go to bed at the same time each night, even on nights off (if possible) – Avoid using the bed and bedroom for other activities (eating, paying bills, studying) – Need for the mind to associate “bed” and “bedroom” with “sleep” If unable to fall asleep.. • Avoid caffeine 8-12 hours before bedtime • Avoid heavy meals immediately before sleep • Avoid alcohol • Try relaxing activities such as warm baths, calm music Caring for the Psychological Self • Exploring the body-mind connection – Good physical care equals a healthy mind • Need down time for thinking and reflection • Make a definite transition between your different areas of life, for example, work life and your home life (transition rituals can be helpful—taking off shoes, changing clothes, enjoying the commute) Caring for the Psychological Self • Hobbies are a necessity • Important to change gears before they become stripped and worthless Caring for the Social Self • • • • Everyone needs friends and fun Do not wait for a 1 week or 2-week “vacation” Plan “mini vacations” Everyone should have at least 1 “fun day” per week • Important to have respite caregivers, either paid or unpaid – Church volunteers, neighbors, family, friends – Do not be afraid to ask!! Stress Management • Stress: strain or pressure – Sources: job (problems with supervisors, coworkers, clients), family, societal demands – Feelings: of pressure, anxiety, “out of control” – Cannot remove stress • Can adjust reaction to stress Stress Management • Incorporates all of the above, plus strategies for relaxing – Guided imagery – Prayer – Breathing exercises Time Management Strategies • Understand what demands are causing the conflict • Strive to achieve a balance between competing demands – Knowing your limits can help you to better use your strengths – Lower standards…a little bit of dust is OK Unhealthy Ways to Deal with Stress • Eating as stress management – When stressed, it is not unusual for people to crave “comfort foods”—e.G. Mashed potatoes, dessert items, chocolate – “It’s not what you are eating, it’s what is eating you” – People do feel better (temporarily) after consuming certain foods, such as chocolate—certain brain chemicals are affected – In the long run, more problems, more stress—vicious cycle Unhealthy Ways to Deal with Stress • Drinking as stress management – Binge vs. Constant drinking – “Need” for a drink to “unwind” – As need grows, potential for dependency – CAGE questions—do you have a problem? • Cut down; Annoyed; Guilt; Eye-opener Unhealthy Ways to Deal with Stress • Other unhealthy ways people “manage” stress – Shopping binges – Temporary euphoria, followed by increased bills (and increased stress) – Smoking – Legal and illegal drugs GUILT??? • Many people feel guilty or selfish if they put their needs ahead of others • Remember the advice from flight attendants: PUT YOUR OXYGEN MASK ON FIRST BEFORE ASSISTING OTHERS WITH THEIRS!! • Taking time out to care for yourself is not a luxury but a necessity