A Preliminary Understanding of the Social

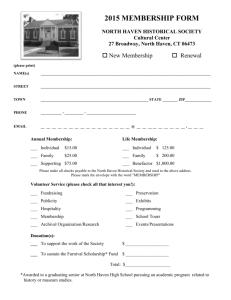

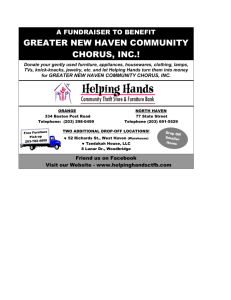

advertisement