Health Impact Assessment of Phase I of the Downtown Crossing Project

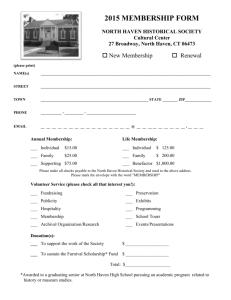

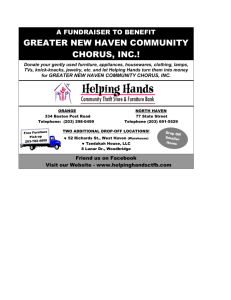

advertisement