75481 Federal Register

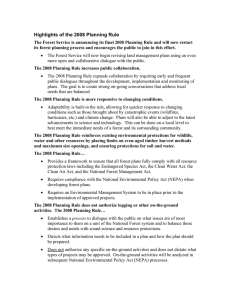

advertisement