Document 10436471

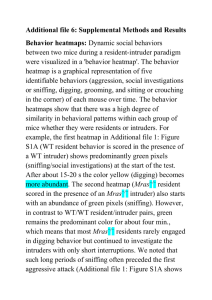

advertisement