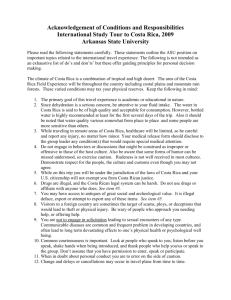

28 April 2005 Original: ENGLISH

advertisement