Document 10436407

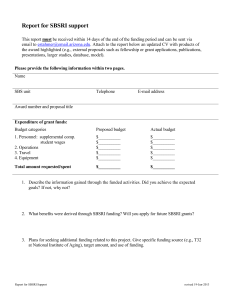

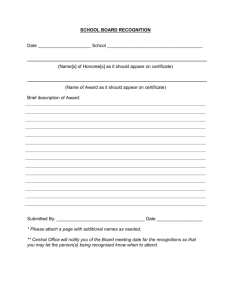

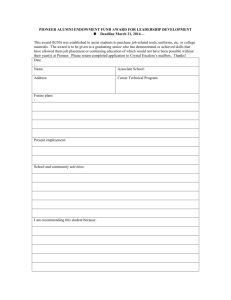

advertisement