Document 10436349

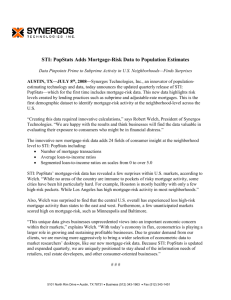

advertisement