E-COMMERCE AND DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2002

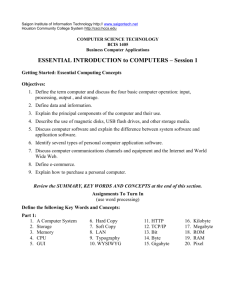

advertisement