E-COMMERCE AND DEVELOPMENT

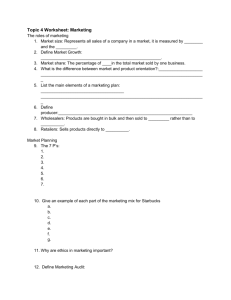

advertisement