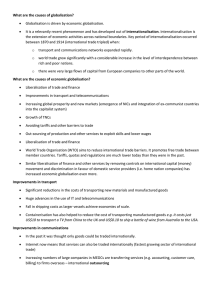

Investment by tnCs and Gender: Preliminary assessment and Way Forward for

advertisement