The Best Beginning: A New Haven Plan for Universal Access to Quality,

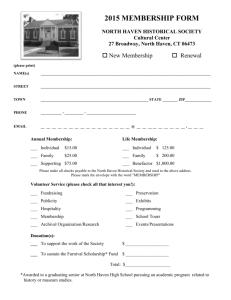

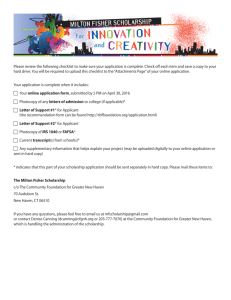

advertisement