Comprehensive, Integrated Community-Wide Safe Schools / Healthy Students Plan For New Haven, Connecticut

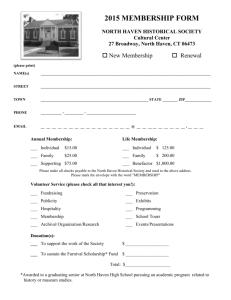

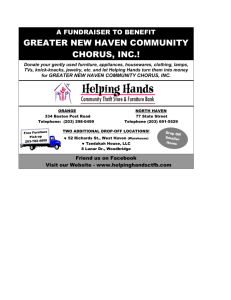

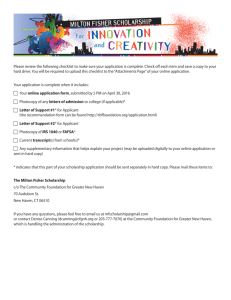

advertisement