2 2014 MAR LIBRARIES

advertisement

Yardstick Competition: An Empirical Investigation Using State Taxes and Media Markets by Lynn Johnson S.B. and S.M. Political Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2001 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ECONOMICS AT THE JVES MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2014 iNf/E OF TECHNOLOGY M!,ASS ACHUSETTS MAR 2 4 2014 © 2014 Lynn Johnson. All rights reserved. LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author.................................................. De ?rtment of Economics February 3, 2014 C ertified by ........................................................ ........................ ........ James M. Poterba Mitsui Professor of Economics Thesis Supervisor A ccepted by..................................... Michael Greenstone 3M Professor of Environmental Economics Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies Yardstick Competition: An Empirical Investigation Using State Taxes and Media Markets by Lynn Johnson Submitted to the Department of Economics on February 3, 2014 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Economics ABSTRACT I investigate whether voters judge the performance of their governor on taxes by comparing him to governors from neighboring states. If voters do make these comparisons, it creates "yardstick competition," where governors are competing with each other as they set taxes. Previous research has shown that governors are punished at the ballot box for raising taxes. However, Besley and Case (AER 1995) find that if governors in neighboring states have also raised taxes the voters are more forgiving. Besley and Case speculate that voters know what is happening in other states through the media. My hypothesis is that if yardstick competition exists, then voters exposed to television from a neighboring state should be influenced by tax changes in that state. For example, there are some counties in eastern Arkansas where voters are watching Tennessee television stations and some in southern Arkansas where they are watching Louisiana television stations. By comparing the voting patterns in these counties in the Arkansas gubernatorial election, I can see if there is any influence coming from the taxes set by the neighboring state. I control for the typical partisan leanings of the county as measured by presidential and senatorial votes in nearby years. Therefore I incorporate county voting data for every election from 1960 to 2000, and I use tax data from the NBER TAXSIM program and other sources. I find only very limited evidence in support of yardstick competition. Specifically, voters seem to make yardstick comparisons for the personal income tax when both governors are Democrats. This may be consistent with a theory where voters can only judge whether a tax increase was warranted when they are comparing governors from the same party, and it supports a growing literature in political science suggesting that voters have different expectations of the two parties on fiscal issues. Thesis Supervisor: James M. Poterba Title: Mitsui Professor of Economics 2 1. Introduction A wealth of anecdotes, as well as substantial scholarly research, suggests that governors are punished at the ballot box for raising taxes. Besley and Case (1995) find, however, that if governors in neighboring states have also raised taxes, then the voters are more forgiving.I The converse is true for tax cuts. Theybriefly speculate that voters must learn about what is happening in other states through the media. My hypothesis is that if such "yardstick competition" exists, then voters exposed to television from a neighboring state should be influenced by tax changes in that state. Local television news devotes considerable coverage to tax changes, budget issues, and the governor. As the executive in each state, the governor is singularly visible and the most likely to be held responsible for the budget by the voters. In fact, 79% of voters can name their state's governor, as compared with 52% for senators.2 Identification of yardstick competition is a great challenge, because there may be common unobserved shocks affecting neighboring states that lead them to mimic each other's tax behavior. Shocks that only affect one state and not its neighbors, such as a natural disaster, could be used to identify this phenomenon, but such an analysis would be complicated by the fact that voters should be aware of the unique situation facing one state and not its neighbors. I introduce a novel approach to determine whether voters make yardstick comparisons between governors that avoids all of these concerns about common unobserved shocks. I look at only those counties where voters are watching out-of-state television, which comprise 18% of the 3000 counties in the United States. Then I analyze whether their vote for governor is influenced by the tax changes in the neighboring state. 1Timothy Besley and Anne Case, "Incumbent Behavior: Vote-Seeking, Tax-Setting, and Yardstick Competition," The American Economic Review, 85:1 (March, 1995), pp. 25-45. 2 Peverill Squire and Christina Fastnow, "Comparing Gubernatorial and Senatorial Elections," PoliticalResearch Quarterly,47:3 (Sept., 1994), p. 708. 3 For example, there are six counties in northern Arkansas where voters are watching Missouri television stations, according to the Nielsen ratings. Likewise, there are seven counties in eastern Arkansas where voters are watching Tennessee television and nine counties in southern Arkansas where they are watching Louisiana television. (See map on last page.) By comparing the voting patterns in these counties in the Arkansas gubernatorial election, I can see if there is any influence coming from the taxes set by the neighboring state. Of course we may be concerned that these out-of-state media market counties are somehow different from the rest of the counties in the state. For example, they might have a particular partisan slant. I control for the partisan leanings of each county using what is called the "normal vote," as measured by presidential and senatorial votes in nearby years. Thus I incorporate voting data at the county level for every election in the country from 1960 to 2000. By looking at television markets which cross-cut state boundaries, and putting in stateby-year fixed effects, I am able to hold constant many factors affecting each election, such as candidate quality and the closeness of the race.This analysis requires that many states contain multiple out-of-state television markets. Luckily this condition holds in the United States. For example, thirty-five states have 2 or more out-of-state television markets. Twenty-three states have 3 or more out-of-state television markets, and 14 states have 4 or more out-of-state television markets. Thus I have sufficient variation to exploit in my analysis. This research is important for understanding the mechanisms used by voters to discipline politicians. It also relates to the determinants of how people vote, as well as the role of the media in elections. Most importantly, it explores the political factors influencing state tax levels. 4 Do voters really care about what is going on in neighboring states? Anecdotal evidence suggests at least that politicians think they do. In her Fiscal Year 2004 Budget Address, Delaware Democratic Governor Ruth Ann Minner announced: "No one wants to stand before you and call for tax increases. But leadership sometimes demands that we take on the tough issues now to prevent more serious problems in the future ... .The next revenue I propose is an increase in the cigarette tax. Since 1991, Delaware's tax has been at 24 cents per pack. This rate is far below our neighboring states, which all collect $1 or more. I am proposing an increase of 26 cents, which will make our new rate 50 cents per pack. This increase will bring in $23.5 million in Fiscal 2004, but will still leave our tax rate far lower than neighboring states." 3 Likewise in New Hampshire, Governor John Lynch in his budget address on February 15, 2005, noted that even after a proposed increase in the cigarette tax it would still be well below that of neighboring states. 4 In his State of the Commonwealth/Budget Address on January 25, 1996, Kentucky Governor Paul Patton explicitly compared Kentucky's taxes with those of surrounding states: "The recent study of the tax structure of Kentucky and surrounding states showed Kentucky had the 6 th lowest overall business tax burden measured in 16 key industries. The area of personal taxation is another matter. In that same tax study, Kentucky ranked second in individual income tax burden.... I'm not proposing that we become the lowest state in individual taxation, but I am proposing that we not be so close to number one." 5 Thus politicians seem to believe that voters can be swayed to think a certain level of taxes is appropriate if neighboring states have adopted a similar level. I find only limited evidence in support of yardstick competition. Specifically, voters seem to make yardstick comparisons with regard to the personal income tax liability for the upper income brackets. This effect only holds when both the governor in the home state and the 3 Budget Address of Governor Ruth Ann Minner, January 30, 2003. www.state.de.us/governor/speeches/ 4 Budget Address of Governor John Lynch, February 15, 2005. www.nh.gov/governor/speeches/documents/021505budget.htm 5 governor in the neighboring state are Democrats. When I analyze total revenues per capita, on the other hand, there is no evidence in support of yardstick competition. I review the relevant scholarly literature in section 2. Section 3 describes the data I use to investigate yardstick competition. Section 4 presents the methodology and shows the results.Section 5 discusses the implications of this study, possibilities for future research, and concludes. 2. Literature Review There has been substantial research showing that governors who tax and spend tend to be punished at the ballot box. Peltzman (1992) finds that voters punish governors, presidents, and senators for raising state and federal spending.Looking at the taxation side, Kone and Winters (1993) and Niemi, Stanley and Vogel (1995) also find that voters punish governors who raise taxes. The latter paper combines data on state tax changes with exit poll data to see if governors' reelection prospects are affected by the tax changes they enact. Its limitation, however, is that it just looks at the number of taxes raised and not the magnitude of the tax change. 6 Furthermore, tax decreases were not analyzed at all due to a lack of data. Niemi, Stanley and Vogel find that the probability of supporting a governor or his party who raised one or more of the sales, personal income, or sin taxes was about .13 less than in those states without a tax increase, even after controlling for changes in personal income that might have resulted from tax increases. Furthermore, the number of taxes increased had a cumulative effect. When a governor raised taxes and then did not stand for reelection (either because of retirement, term limits, or a primary 5 State of the Commonwealth / Budget Address of Governor Paul Patton, January 25, 1996. Commonwealth of Kentucky Web Server. 6 Richard G. Niemi, Harold W. Stanley, and Ronald J. Vogel, "State Economies and State Taxes: Do Voters Hold Governors Accountable," American JournalofPoliticalScience, 39:4 (November, 1995), 6 loss), they find that the impact of the tax increases carried over to their party's candidate. They find similar effects when looking at Democrats versus Republicans. Downs (1960) describes many reasons why voters do not fully perceive the benefits that result from taxation. Many of the benefits are preventative and remote, such as spending to regulate food quality or prevent a revolution in a foreign land. Also, the benefits often involve substantial uncertainty, such as in foreign policy. Taxes, on the other hand, impose an immediate cost. Kone and Winters point out that these perceptions may lead voters to vote against governors who raise taxes. They find that sales tax increases are punished more heavily at the polls than are income tax increases. 7 Besley and Case (1995) describe a more nuanced political scene where voters are not simply voting against all taxation. Instead, voters are portrayed as potentially opposing even a small tax increase if they feel it was unwarranted, but perhaps tolerating a large tax increase if taxes are rising rapidly everywhere. Besley and Case build a theoretical model of asymmetric information where voters face political agency issues because the governor possesses informationthat voters do not. Voters address this problem by comparing the taxes their governor sets to those set by neighboring governors. The result is that governors are actually competing with each other as they set taxes. Indeed, Berry and Berry (1992) argue that governors raise taxes when they have the political opportunity to do so, and that one such opportunity is when the governor of a neighboring state has raised taxes.8 They find confirmation for this theory in an empirical analysis of state tax adoptions and rate increases throughout the twentieth century. pp. 936-957. 7 Susan L. Kone and Richard F. Winters, "Taxes and Voting: Electoral Retribution in the American States," The JournalofPolitics 55:1 (Feb., 1993), p. 33. 8 Frances Stokes Berry and William D. Berry, "Tax Innovation in the States: Capitalizing on Political 7 If such yardstick competition is present, it leads to tax mimicking between sub-national entities. Indeed, tax-mimicking is observed not only for the American states, but also between counties.9 Ladd (1992) shows that when one county's tax increases by one dollar, its neighbor's tax increases by about 50 cents. It is difficult to identify yardstick competition because there may be common unobserved shocks affecting neighboring states that lead them to mimic each other's tax behavior. Besley and Case use two strategies to test empirically for yardstick competition. The first uses termlimited governors. This is problematic if we think that term-limited governors may be interested in running for another political office. Or, they may care about how their political party fares in the next election. Thirdly, they may care about theirreputation or legacy. Besley and Case's second approach is to use an instrumental variables strategy. They instrument for tax changes using demographic and economic variables. In this case we may be concerned that these demographic and economic variables are also having a direct impact on electoral outcomes, thereby violating the exclusion restriction. Besley and Case find that if a governor is eligible to run again, then when a neighbor increases (decreases) taxes by $1 his own state will increase (decrease) taxes by 20 cents.This result holds when they look at both the personal income tax liability and at per capita income, sales, and corporate tax revenues. On the other hand, Rork (2003) finds the opposite result for personal income taxes. He finds that an increase in your neighbor's personal income tax is associated with a small decrease in your state's personal income tax. He finds a similar result for the sales tax. For other taxes, however, which comprise a relatively small share of total state Opportunity," American JournalofPoliticalScience, 36:3 (August, 1992), pp. 715-742. Frances Stokes Berry and William D. Berry, "The Politics of Tax Increases in the States," American JournalofPolitical Science, 38:3 (August, 1994), pp. 855-859. 9 H. F. Ladd, "Mimicking of Local Tax Burdens Among Neighboring Counties," Public Finance 8 revenue, he finds a positive responsiveness between a state and its neighbors. These includetaxes on motor fuel, tobacco, and corporate income; Rork asserts that these taxes have a base that is relatively more mobile and that is what makes them different. There is also evidence of state spillovers on the spending side as well as on the tax side. Baicker (2005) finds that each dollar increase in your neighbor's spending increases your own spending by almost 90 cents.' 0 Case, Hines and Rosen (1993) find that a state's expenditures depend on the spending of similar states. Thus they are using states which are similar rather than necessarily being geographic neighbors. They find that a $1 increase in the spending of one state increases spending in its "neighbor" by 70 cents, even after controlling for fixed state effects, year effects, and common random shocks among neighbors." Allers and Elhorst (2005) note that tax mimicry between states can be the result of expenditure spillovers, Tiebout competition, or yardstick competition. My analysis provides little evidence that voters make yardstick comparisons. It is silent on whether expenditure spillovers or Tiebout competition may be present, but would suggest this as a direction for future research seeking to explain tax mimicking. 3. Data For each county in the United States, I have data on what media market a plurality of households are watching. 12This data comes from ratings taken by Nielsen and Arbitron and is widely used by marketing and advertising firms. Arbitron states, "The Area of Dominance Quarterly,20 (1992), 450-467. 10 Katherine Baicker, "The Spillover Effects of State Spending," JournalofPublic Economics 89:2-3, pp. 529-544. 11 Anne C. Case, James R. Hines, Jr., and Harvey S. Rosen, "Budget Spillovers and Fiscal Policy Interdependence: Evidence from the States," JournalofPublicEconomics 52 (1993) 285-307. 12Broadcastand Cable Yearbook, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000. 9 Influence [ADI] is a geographic market design that defines each television market exclusive of the others, based on measurable viewing patterns. Each market's ADI consists of all counties in which the home market stations receive a preponderance of viewing, and every county in the continental U.S. is allocated exclusively to one ADI." Data is available for 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000. Eighteen percent of the 3000 counties in the United States are watching media from out of state. I also have county voting data for every election.1 3 I create a normal vote variable to capture a county's partisanship, similar to Bond, Covington, and Fleisher (1985).14 The normal vote variable is the simple average of any presidential and senate votes for the incumbent governor's party held during a nine-year moving window of four years before and four years after the year in question. I do not include thecurrent election year to avoid any possible coattails effect. This variable, with its floating average, has the virtue of capturing a county's partisanship using nongubernatorial, statewide races. It smoothes out spikes resulting from just one election while allowing for a county's partisanship to shift over time. This is especially important for counties in the South, which underwent a gradual party realignment following the passage of the Voting Rights Act. The normal vote controls for the fact that counties in out-of-state media markets may have a particular partisan bias that is distinct from other counties in the state. Counties in out-ofstate media markets are also different from in-state media market counties because they may be exposed to fewer television campaign ads. This is similarly true for senate races, which provide a good comparison group, because the senate vote should not be affected by changes in state taxes. 3 1 GeneralElection Dataforthe UnitedStates, 1950-1990i.ICPSR.AmericaVotes (1992, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000). 10 Different states use a variety of taxes at different levels, and in an attempt to capture all these moving parts, I use two tax data sets. The first covers the personal income tax and is obtained from the TAXSIM program at the National Bureau of Economic Research and covers 1977-2000. It has three series giving the state personal income tax liability of a childless couple earning $20,000, $40,000, and $80,000 a year respectively, in constant 1977 dollars. Adjusted for inflation, these series are the equivalent of $67,000, $134,000, and $268,000 in 2006. Median family income in 2006 is about $58,000. So these series may seem relatively high, but as we will see, all the action actually occurs in the upper brackets. This data set has the advantage of capturing the taxes that the governor and the legislature intend to charge the taxpayers. Its main limitation, however, is that it only encompasses the personal income tax, and during this period many states were shifting to a larger reliance on the sales tax. Indeed, in 1980 there were nine states that had no personal income tax whatsoever.' 5These states are included in the analysis with values of zero for the personal income tax liability. However, omitting the states with no personal income tax from the analysis does not substantially alter the results. The personal income tax comprised 36% of the total tax revenues and licensing fees collected by state governments in the United States in the year 2000.16 The second data set is the total tax revenue per capita collected by a state.This data set is provided by the United States census, and I use data from 1960 to 2000. It has the advantage of covering all forms of taxes, but has the disadvantage of being sensitive to changes in the macro 4 Jon R. Bond, Cary Convington, and Richard Fleisher, "Explaining Challenger Quality in Congressional Elections," The JournalofPolitics 47:2 (June, 1985) 510-529. 15 The states with no personal income tax in 1980 are Alaska, Connecticut, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming. Connecticut later acquired an income tax, but it is still excluded from the analysis. Source: TAXSIM. 16 "State Government Tax Collections: 2000" from the TaxPolicyCenter. 11 economy of the state. Hence it will show tax increases when the economy grows even if there were no change in the tax policy. For all of the tax data I only look at changes rather than levels, because the share of taxes borne by local government varies widely across different states. 4. Analysis and Results To test whether voters are really making yardstick comparisons between governors, I run the following regression: Vt- NormalVotej= fTaxCompj, +pstate*year dummies+ a + y where V is gubernatorial vote for the incumbent or his party in countyj at yeart.NormalVote is the normal vote for the incumbent's party in countyj at year t. Hence the dependent variable is the difference between the gubernatorial vote and the normal vote.Since the normal vote captures a county's partisanship, this structure provides an intuitive interpretation. The dependent variable is how much better than the normal vote the governor fares. TheTaxComp variable is a composite variable that captures the relative tax changes in the home state and in the neighboring state. (See figure below.) It equals 0 if the in-state tax change matches the tax change in the media market state. For example, it equals 0 if both states raised taxes or both kept taxes flat or both lowered taxes. If the home state lowered taxes and the neighboring state kept taxes flat, it equals 1. It also equals 1 if the home state kept taxes flat and the neighboring state raised taxes. If the home state lowered taxes and the neighboring state raised taxes, then the TaxComp variable equals 2. The converse holds for values of -I and -2. In this manner, my theory predicts that swill be positive; the voters should reward the governor when she lowered taxes and the neighboring state raised taxes. 12 Figure: The TaxComp Variable Tax Change in the Neighboring State Tax Change in the HomeState Decrease Flat Increase Decrease 0 1 2 Flat -1 0 1 Increase -2 -1 0 I include state-by-year dummies to control for many other factors that may be affecting the election. For example, this holds candidate quality constant in each election. Also, the closeness of the race is held constant. This structure also captures partisan tides. In the analysis I include only counties in an out-of-state media market because it is not clear what voters in counties with in-state media markets believe is happening to taxes in other states. They may assume that taxes elsewhere are flat, or assume that taxes elsewhere match their own. Furthermore, many television stations also provide coverage for neighboring states in their broadcast area, and so in these cases the voters would have knowledge of what is actually happening in neighboring states. There are many other reasons why out-of-state media market counties are different from in-state media market counties. First of all, they do not receive television campaign ads, unless the campaigns spend precious resources to buy time in the neighboring television market. Secondly, they may not be able to watch the televised debates. Thirdly, to compensate for this lack of contact, the campaigns target them more heavily with 13 other strategies, such as campaign visits by candidates or their staff.'7 Therefore, I think the cleanest test of the theory is to compare counties watching television from different states. Eighteen percent of the 3000 counties in the United States belong to an out-of-state television market. Such counties receiving out-of-state media tend to be very slightly more Democratic than counties receiving in-state media; the average two-party vote share received by the Democratic gubernatorial candidate in out-of-state media market counties is 50.1%, as compared with 48.9% for in-state media market counties. As we would expect, out-of-state media market counties do tend to be smaller in population, with a median population of 18,000, rather than 24,100. I omit elections where the governor is running unopposed by any major party candidate.I include only those elections where the governor has served a four-year term. I look at the net change in taxes over a three year period, because it takes a year for a new governor's budget to be implemented. Table 1 presents examples of the TaxComp values across different specifications for a few states. I use dummy variables for a tax increase or decrease of more than $50, $100, and $200. For each of these cutoffs, the TaxComp variable takes on a value of -2, -1, 0, 1, or 2. Cutoffs can be useful because a small tax change may not be salient to the voters. I also use TaxCompLinear, which is the tax increase in the media market state minus the tax increase in the home state. This is also useful because it incorporates the degree of the relative tax change in its full magnitude. Let us consider those counties in Arizona in the gubernatorial election year of 1982 that are receiving television from New Mexico. Over the past three years in Arizona the total Stephen Ansolabehere, Erik Snowberg, and James M. Snyder, "Television and the Incumbency Advantage," Legislative Studies Quarterly, 31:4 (November, 2006) p. 469-490. 17 14 revenues per capita had increased by $79, while in New Mexico they had increased by $129. Thus the TaxCompLinear value is 129 - 79 = 50. Since both states had a tax increase of more than $50, TaxComp equals 0 at the $50 cutoff. At the $100 cutoff level, New Mexico had a tax increase and Arizona's taxes are considered to have remained flat, so the TaxComp variable has a value of 1. At the $200 cutoff level, both states are considered to have kept their taxes relatively flat, and so the TaxComp variable equals 0. Table 2 presents summary statistics. The unit of observation is the county-election year. The number of observations varies with the number of years available in the data set. The TaxComp variables all have a mean of close to 0, which is appropriate. However, the standard deviations are sufficiently large, for a variable that is bounded by -2 and 2, to indicate that there is good variation present. The TaxCompLinear variables also have means that for their scale are close to zero. I show the pair wise correlations between the TaxComp and TaxCompLinear variables in Table 3.It presents the $80,000 series for the income tax liability. (The $20,000, $40,000, and $80,000 series are correlated at a rate of .78-.95 for those states with an income tax.) For the various income tax liability measures, the correlations are high. For the various total revenue per capita measures, the correlations are lower. The correlations between the tax measures for the income tax liability measures and the total revenue per capita measures are very low and sometimes negative. For example, TaxCompLinear for the income tax liability and TaxCompLinear for total revenues have a correlation of .16. When we look at sales tax rate data, it is correlated at a level of about -.3 with the income tax liability series in states that have a personal income tax.18 This suggests that policymakers use the personal income tax and the sales 18 Sales tax rate data come from the Council of State Governments, The Book of the States, 1960-2000, Lexington, KY. 15 tax as substitutes. Since the personal income tax and the sales tax make up the bulk of state tax revenue in roughly equal portions, if they are acting as substitutes, that would explain why the correlations between the personal income tax and total revenues per capita are so low. This is another reason why total revenues per capita may be the more satisfying measure to use. On the other hand, voters may respond differently to different types of taxes, as Kone and Winters point out, and therefore it is interesting to look at the personal income tax liability as well. After all, a sales tax is collected in tiny increments, with each purchase made, while taxpayers feel the personal income tax as a big chunk deducted from their paycheck. Table 4 presents the basic regressions. Yardstick competition predicts a positive coefficient on the TaxComp variable. Nothing is significant. Thus we would tend to reject the hypothesis of yardstick competition.Indeed, this is not an instance of marginal results that are just short of significance; more often than not, the coefficient is negative. The political science literature suggests that voters have different expectations of the two parties on fiscal issues. Lowry, Alt, and Ferree state, "Voter reactions to taxes and spending relative to the state economy are conditional on expectations, which differ for each party."S9 Therefore, I add interaction terms for the parties of the governor in the home state and the neighboring state. I use the following regression: Vt- NormalVotejt= t1DemDemjt*TaxCompt + 2 RepRepjt*TaxCompjt + P3Mixedjt*TaxCompjt +pstate*year dummies+ a +Fjt where DemDem is a dummy variable taking on a value of 1 if both the home and the neighboring governor are Democrats and taking on a value of 0 otherwise. RepRep is a similar dummy variable for when there are two Republican governors, and Mixed is another dummy taking on a 19 Robert C. Lowry, James E. Alt and Karen E. Ferree, "Fiscal Policy Outcomes and Electoral Accountability in the American States," American PoliticalScience Review 92:4 (December, 1998), p. 7 5 9 - 7 7 4 . 16 value of 1 when the two governors are from opposing parties. This way of structuring the interaction terms provides intuitive coefficients and standard errors. Regressions with the interactions terms are presented in Table 5. At the $40,000 income level and at the $80,000 income bracket, there is yardstick competition between Democratic governors. The coefficient has a magnitude of 2-5.5 percentage points of the two-party vote share. This means that if the Democrat at home lowers taxes, while the neighboring Democratic governor raises taxes, the voters reward their governor with about 6 percentage points of the twoparty vote share. The advantage of the TAXSIM data is that it allows you to break the results down by income series. Yardstick competition is evident when taxes are changed for the upper income brackets. People in the upper income brackets vote in higher numbers. 2 0 They may know more about campaign issues, and they may be more savvy consumers of media.Tichenor, Donohue, and Olien (1970) argue that "As the infusion of mass media information into a social system increases, segments of the population with higher socioeconomic status tend to acquire this information at a faster rate than the lower status segments," leading to an increase in the "knowledge gap" between the upper and lower status groups. Furthermore, it is also possible that people in the upper income brackets are more influential in elections, perhaps through such mechanisms as campaign donations. Another observation in Table 5 is that often there is a negative coefficient when there are two Republican governors. This would tend to reject the hypothesis of yardstick competition. It 20Kim Quaile Hill and Jan E. Leighley, "The Policy Consequences of Class Bias in State Electorates" American JournalofPoliticalScience 36:2 (May, 1992), pp. 351-365. Stephen D. Shaffer, "Policy differences between Voters and Non-Voters in American Elections," The Western PoliticalQuarterly 35:4 (Dec., 1982), pp.4 9 6 -5 10 . 21 P. J. Tichenor, G. A. Donohue, C. N. Olien, "Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge," The Public Opinion Quarterly 34:2 (Summer, 1970), pp. 159-170. 17 suggests that voters punish their governor if he holds the line on taxes while the neighboring governor raises taxes. While this may seem implausible, it is perhaps more consistent with a story of spillovers on the spending side. For example, voters might punish their governor because local schools are performing poorly compared to the neighboring state's schools. And the local schools may be performing worse because they have less funding due to a lower tax regime. Turning to Table 6, we find the results for total revenues per capita with party interaction terms.The effect of TaxComp when both governors are Democrats is never significantly different from zero. The effect of TaxComp when there is one Republican and one Democrat is sometimes positive and significantly different from zero, suggesting that some yardstick competition is present. Up until now, we have been looking only at elections where governors are standing for reelection. Now we want to turn to look at what happens when the incumbent does not stand for reelection, either due to term limits or other reasons. Typically we think of voters as making a decision based on limited information and taking cues based on party labels. In this case, if a governor has raised taxes and then does not stand for reelection, his party's candidate may be punished for the tax increase. Indeed, King (2001) finds that economic conditions in a state carry over to affect the electoral prospects of an incumbent's partisan successor. 22Here there is scope for yardstick competition to occur. On the other hand, it is possible that voters perceive the new candidate as being sufficiently differentiated from the old governor despite being in the same party. Table 7 presents the overall results for what happens to the incumbent governor's party when he does not stand for reelection. The TaxComp variable is never positive and 18 significantexcept for total revenues per capita at the $200 cutoff level. I add party interaction terms to these results in Table 8 for the personal income tax. Again, nothing is positive and significant. Apparently the yardstick competition that we saw when both governors were Democrats and the home governor was running for reelection does not carry over to his party if he does not stand for reelection. We see the results for total revenues per capita in Table 9. There are only significant and positive coefficients on TaxComp when there are two Democrats in the linear case and one Democrat and one Republican at the $200 cutoff level. 6. Conclusion Yardstick competition appears to be confined to the personal income tax in the upper income brackets when both the governors are Democrats. People in the upper income brackets vote in disproportionately high numbers. They may also be more sophisticated consumers of media. The finding that the effect holds when both governors are Democrats is consistent with a theory where voters can only judge whether a tax increase was warranted when they are comparing governors from the same party. It supports a growing literature in political science suggesting that voters have different expectations of the two parties on fiscal issues. I would like to repeat this analysis looking only at whether the governor has raised taxes in the year prior to the election rather than looking at the whole three-year lag. Other studies involving what is called retrospective voting, where voters are looking backward and judging the past performance of the incumbent, suggest that the window of a voter's memory is quite short. For example, Kiewiet and Rivers note that most researchers use a one-year lag, and that 22.James D. King, The JournalofPolitics, 63:2 (May, 2001) pp. 585-597. 19 longerlags tend to bias you towards finding the null hypothesis.23 Such an analysis might suffer from a lack of variability in the data, however, becauser research from Mikesell (1978) suggests that tax increases are least likely to happen in the years of gubernatorial elections.24 It would be interesting to extend this analysis by breaking it down by terms of divided government as compared with undivided government. Voters may place more responsibility for fiscal issues in the governor when his party also controls the legislature. On the other hand, in situations of divided government, the governor and legislature can blame each other for the tax increase. It would furthermore be interesting to break it down by which governors have the line item veto. Do voters hold governors with the line item veto more responsible for the budget? Shifting some of the responsibility for the budget from the legislature to the governor should intensify any yardstick effects with respect to the governor. By analyzing media markets and state taxes, I find scant evidence of voters making yardstick comparisons in judging the performance of their governor on taxes. To the degree that tax mimicry is observed between neighboring states, it would be worth investigating the influence of expenditure spillovers. Given the balanced budget pressures faced by the states, spillovers on the spending side would usually be associated with similar tax adjustments.This may be a fertile area for future research. D. Roderick Kiewiet and Douglas Rivers, "A Retrospective on Retrospective Voting," PoliticalBehavior 6:4 (1984) p. 372. 24John L. Mikesell, "Election Periods and State Tax Policy Cycles," Public Choice, 33:3 (March, 1978), 99-106. 23 20 Bibliography Allers, Maarten A. and J. Paul Elhorst.2005. "Tax Mimicking and Yardstick Competition Among Local Governments in the Netherlands."InternationalTax and Public Finance 12 (2005), 493-513. Ansolabehere, Stephen, Erik Snowberg, and James M. Snyder. 2006. "Television and the Incumbency Advantage." Legislative Studies Quarterly.31:4 p. 469-490. Baicker, Katherine. 2005. "The Spillover Effects of State Spending."JournalofPublic Economics.Vol. 89, no. 2-3. Berry, Frances Stokes and William D. Berry. 1992 "Tax Innovation in the States: Capitalizing on Political Opportunity."AmericanJournalofPoliticalScience, 36:3, 715-742. . 1994. "The Politics of Tax Increases in the States." American Journalof PoliticalScience, 38:3, 855-859. Besley, Tim and Anne Case.1995. "Incumbent Behavior: Vote Seeking, Tax Setting, andYardstick Competition."American Economic Review 85(1), 25-45. . 1995. "Does Electoral Accountability Affect Economic Policy Choices? Evidence from Gubernatorial Term Limits." QuarterlyJournalofEconomics 110(3), 769-798. Bond, Jon R., Cary Convington, and Richard Fleisher. 1985. "Explaining Challenger Quality in Congressional Elections."The Journal ofPolitics47:2 (June) 510-529. Broadcastand Cable Yearbook (1970, 1980, 1990, 2000). Case, Anne, James Hines, Jr. and Harvey Rosen. 1993. "Budget Spillovers and Fiscal Policy Interdependence: Evidence from the States." JournalofPublic Economics 52(3), 285-307. Congressional Quarterly, America Votes serial 1992, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000. Washington: ElectionsResearchCenter. Council of State Governments.The Book of the States. 1960-2000. Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments. Downs, Anthony. 1960. "Why the Government Budget is Too Small in a Democracy," World Politics 12:4, 541-563. Feenberg, Daniel and Elisabeth Coutts.1993. "An Introduction to the TAXSIM Model." JournalofPolicy Analysis and Management 12:1, 189-194.www.nber.org/taxsim/ Hill, Kim Quaile and Jan E. Leighley. 1992. "The Policy Consequences of Class Bias in State Electorates."American JournalofPoliticalScience 36:2, 351-365. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. 1995. GeneralElection Dataforthe United States, 1950-1990 [Computer file]. ICPSR ed. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [producer and distributor]. Kiewiet, D. Roderick and Douglas Rivers. 1984. "A Retrospective on Retrospective Voting."PoliticalBehavior 6:4,pp. 369-393. King, James D. 2001. The JournalofPolitics 63:2, 585-597. Kone, Susan L. and Richard F. Winters. 1993. "Taxes and Voting: Electoral Retribution in the American States." JournalofPolitics 55:23-39. Ladd, H. F. 1992. "Mimicking of Local Tax Burdens Among Neighboring Counties." Public Finance Quarterly,20, 450-467. 21 Lowry, Robert C., James E. Alt and Karen E. Ferree. 1998. "Fiscal Policy Outcomes and Electoral Accountability in the American States."AmericanPoliticalScience Review 92:4, p. 7 5 9 -7 7 4 . Lynch, Governor John. Budget Address, February 15, 2005. www.nh.gov/governor/speeches/documents/021505budget.htm Mikesell, John L. 1978. "Election Periods and State Tax Policy Cycles." Public Choice 33:3, 99-106. Minner, Governor Ruth Ann. Budget Address, January 30, 2003. www.state.de.us/governor/speeches/ Niemi, Richard G., Harold W. Stanley, and Ronald J. Vogel. 1995. "State Economies and State Taxes: Do Voters Hold Governors Accountable?" American Journalof PoliticalScience39:4, 936-957. Peltzman, Sam. 1992. "Voters as Fiscal Conservatives." The QuarterlyJournalof Economics, 107:2, 327-361. Rork, Jonathan C. 2003. "Coveting Thy Neighbors' Taxation." National Tax Journal. LVI:4, 775-787. Shaffer, Stephen D. 1982. "Policy Differences between Voters and Non-Voters in American Elections."The Western PoliticalQuarterly35:4, 496-5 10. Squire, Peverill and Christina Fastnow. 1994. "Comparing Gubernatorial and Senatorial Elections."PoliticalResearch Quarterly47:3, 705-720. State of the Commonwealth / Budget Address of Governor Paul Patton, January 25, 1996. Commonwealth of Kentucky Web Server. TaxPolicyCenter. "State Government Tax Collections: 2000." Tichenor, P. J., G. A. Donohue, C. N. Olien. 1970. "Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge."The Public Opinion Quarterly34:2, 159-170. 22 Table 1: Understanding the TaxComp Variable State Election Year Neighboring State Alabama 1990 Georgia Alabama Alabama Alabama 1990 1998 1998 Mississippi Georgia Mississippi 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 29 65 Arkansas Arkansas Arkansas Arizona 1990 1990 1990 1982 Louisiana Missouri Tennessee N. Mexico 0 0 0 0 0 -1 -1 1 0 0 0 0 3 -30 -61 50 Arizona 1994 N. Mexico 0 0 1 79 California California California California California California 1970 1970 1978 1978 1978 1986 Arizona Nevada Arizona Nevada Oregon Arizona 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 -1 -1 -1 -1 50 70 -72 -47 -24 -113 California 1986 Nevada 0 0 -1 -125 California 1986 Oregon 0 0 -1 -166 California California California 1994 1994 1994 Arizona Nevada Oregon 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 40 225 104 Colorado 1970 Kansas -1 0 0 -8 Colorado 1970 N. Mexico 0 0 0 31 Colorado 1970 Utah 0 0 0 13 Colorado 1970 Wyoming 0 0 0 10 Colorado 1978 Kansas 0 0 0 -5 Colorado Colorado 1978 1978 N. Mexico Wyoming 0 0 0 0 0 1 40 131 Colorado 1982 Kansas 1 1 0 66 Colorado Colorado Colorado Colorado Colorado Colorado 1982 1982 1990 1990 1994 1994 N. Mexico Wyoming N. Mexico Utah N. Mexico Utah 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 -1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 82 577 24 -16 77 72 Connecticut Connecticut Connecticut Connecticut Delaware Delaware 1978 1978 1986 1998 1968 1968 New York Rhode Isl. New York New York Maryland Penn. 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 -29 8 -28 -283 24 10 TaxComp Value Total Reve ues per capita $50 cutoff $100 $200 0 0 0 1 23 Linear 37 Table 2: Summary Statistics When the governor stands for reelection: Income Tax Liability: Gubernatorial Vote NormalVote $20,000 series: TaxComp, $50 cutoff for a tax increase or decrease TaxComp, $100 cutoff TaxComp, $200 cutoff TaxComp, $400 cutoff TaxCompLinear $40,000 series: TaxComp, $50 cutoff for a tax increase or decrease TaxComp, $100 cutoff TaxComp, $200 cutoff TaxComp, $400 cutoff TaxCompLinear $80,000 series: TaxComp, $50 cutoff for a tax increase or decrease TaxComp, $100 cutoff TaxComp, $200 cutoff TaxComp, $400 cutoff TaxCompLinear Total Revenues per capita: Gubernatorial Vote NormalVote TaxComp, $50 cutoff for a tax increase or decrease TaxComp, $100 cutoff TaxComp, $200 cutoff TaxComp, $400 cutoff TaxCompLinear Mean Standard Deviation Number of Observations 60.7 51.0 13.1 9.7 1473 1473 .123 .058 -.006 -.006 60.7 .701 .518 .354 .190 13.1 1473 1473 1473 1473 1473 .129 .035 .021 -.019 19.4 .993 .801 .599 .313 263 1473 1473 1473 1473 1473 .139 .148 .019 -.049 31.6 1.04 .976 .810 .614 612 1473 1473 1473 1473 1473 58.0 51.5 13.7 10.8 2115 2115 .005 .019 -.010 -.006 -.043 .351 .473 .485 .125 93.3 2115 2115 2115 2115 2115 TaxCompLinear is the tax increase in the media market state minus the in-state tax increase. 24 Table 3: Correlations of the TaxComp Variable Income Tax Liability ($80,000 Series) $50 $100 $200 Linear cutoff Total Revenues per capita $50 $100 $200 Linear 1.00 .63 1.00 cutoff $50 Income cutoff 1.00 Tax Liabilit $100 $200 .91 .80 1.00 .85 1.00 y Linear .65 .67 .79 1.00 Total Revenu $50 cutoff $100 .01 .03 -.04 -.03 -.14 .00 -.24 .04 1.00 .36 1.00 $200 Linear .15 .14 .14 .16 .24 .20 .18 .16 .05 .31 .13 .43 es per capita TaxCompLinear is the tax increase in the media market state minus the in-state tax increase. the other variables take on values of -2, -1, 0, 1, and 2. 25 All Table 4: Voting Results When the Governor Stands for Reelection Income Tax Liability of $20,000 (N=1473) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear -.598 (.523) .786 .358 (.643) .786 -2.08 (1.10) .787 -1.11 (2.28) .786 -.0012 (.0029) .786 Income Tax Liability of $40,000 (N=1473) Cutoff for a tax increase or $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear .555 (.402) .786 -.757 (.466) .786 -.627 (.558) .786 1.19 (1.13) .786 .0001 (.0014) .786 decrease: TaxComp R-squared Income Tax Liability of $80,000 (N=1473) Cutoff for a tax increase or $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear .195 (.376) .786 -.240 (.393) .786 -.640 (.465) .786 -.963 (.624) .786 .0001 (.0006) .786 decrease: TaxComp R-squared Total Revenues per capita (N=2115) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear .623 (.706) .823 -.979 (.522) .810 .150 (.468) .823 -4.04 (.2.45) .823 -.0034 (.0027) .823 Parentheses contain standard errors. Specification: Vjt- NormalVoter- PTaxCompjt +pstate*year dummies+ a + where V is the gubernatorial vote. 26 j Table 5: Income Tax Results Broken Down by Party When the Governor Stands for Reelection Income Tax Liability of $20,000 (N=1473) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: DemDem*TaxComp RepRep*TaxComp Mixed*TaxComp R-squared $50 .261 $100 1.51 $200 -.026 $400 1.70 Linear .0023 (1.12) -3.11* (.752) -.042 (.706) .789 (1.14) -.145 (1.11) .522 (.831) .786 (2.22) -1.58 (2.24) -3.79* (1.19) .788 (3.09) Dropped -6.38* (2.13) .787 (.0049) -.0158* (.0060) -.0037 (.0033) .803 Income Tax Liability of $40,000 (N=1473) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear DemDem*TaxComp 1.97* (.875) 1.88* (.852) 5.48* (1.19) 2.62 (2.03) .0086* (.0029) RepRep*TaxComp -.453 -2.80* -2.29* 2.91 -.0101* Mixed*TaxComp (.624) 1.16* (.696) .816 (.928) -.941 (3.35) -.513 (.0032) .0009 (.485) (.596) (.767) (1.17) (.0016) .788 .790 .791 .786 .789 R-squared Income Tax Liability of $80,000 (N=1473) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: DemDem*TaxComp RepRep*TaxComp Mixed*TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear 1.97* (.793) -.070 (.603) .181 (.446) .787 2.56* (.814) -.251 (.644) -.033 (.473) .788 4.49* (1.01) -2.65* (.702) -.614 (.566) .791 5.36* (1.20) -3.30* (1.02) -1.53 (.805) .792 .0061* (.0013) -.0031 (.0016) -.0008 (.0007) .791 Parentheses contain standard errors. Specification: Vjt- NormalVoteyt= p1DemDemt*TaxCompjt + p2RepRepjt*TaxCompjt + P3Mixedjt*TaxComp +pstate*year dummies+ a + y7j where V is the gubernatorial vote and DemDern is a dummy variable equaling 1 if both governors are Democrats and 0 otherwise. 27 Table 6: Total Revenue Results Broken Down by Party When the Governor Stands for Reelection Total Revenues per capita (N=2115) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: DemDem*TaxCom p RepRep*TaxComp Mixed*TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear -1.41 (1.88) 1.56 (1.07) 2.36* (1.16) .824 -.412 (.984) -4.25* (.962) -.059 (.678) .825 .286 (1.05) -2.56* (.826) 1.13* (.570) .824 1.44 (3.23) -3.20 (4.21) -8.11* (2.69) .824 .0091 (.0048) -.013* (.005) -.004 (.003) .824 Parentheses contain standard errors. Specification: Vjt- NormalVote= + p3 Mixedjt*TaxCompjt iDemDemjt*TaxCompjt + 2RepRepjt*TaxCompjt +9state*year dummies+ a + Ejt where V is the gubernatorial vote and DemDem is a dummy variable equaling 1 if both governors are Democrats and 0 otherwise. RepRep is a dummy variable equaling 1 if both governors are Republicans and 0 otherwise. Mixed is a dummy variable equaling 1 if there is one Democratic governor and one Republican governor. 28 Table 7: Voting Results for the Incumbent's Party When the Governor Does Not Stand for Reelection Income Tax Liability of $20,000 (N=1396) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear -2.64* (.551) .689 -2.99* (.688) .688 -2.28 (1.18) .684 -4.67 (2.40) .684 -.0101* (.0031) .686 Income Tax Liability of $40,000 (N=1396) Cutoff for a tax increase or $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear -.682 (.451) .684 -.851 (.526) .684 -1.14 (.664) .684 -.346 (1.10) .683 -.0016 (.0013) .683 decrease: TaxComp R-squared Income Tax Liability of $80,000 (N=1396) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear -.673 (.423) .684 -.920 (.461) .684 -.495 (.565) .683 -1.19 (.637) .684 .0000 (.0005) .683 Total Revenues per capita (N=2062) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear 1.29 (.785) .139 (.592) 1.08* (.506) Dropped -.0026 (.0032) .739 .739 .739 Parentheses contain standard errors. Specification: Vjt- NormalVote= fTaxCompjt +pstate*year dummies+ a + y where V is the gubernatorial vote. 29 .739 Table 8: Income Tax Results Broken Down by Party For the Incumbent's Party When He Does Not Stand for Reelection: Income Tax Liability of $20,000 (N=1396) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: DemDem*TaxComp RepRep*TaxComp Mixed*TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear -.504 (.687) -4.92* (.800) -.632 (.639) .692 -2.38* (.955) -5.11* (1.02) -1.52 (.976) .690 -3.64* (1.67) -1.24 (2.71) -4.60* (2.25) .685 -10.7* (4.22) -1.77 (2.92) Dropped .685 -.0087* (.0044) -.0160* (.0047) .0017 (.0058) .687 Income Tax Liability of $40,000 (N=1396) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: DemDem*TaxComp RepRep*TaxComp Mixed*TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear .943 (.629) -5.83* (.900) -.140 .586 (.688) -3.96* (.859) .212 .214 (.915) -5.41* (1.14) .417 -3.46 (1.44) .820 (2.60) 1.06 -.0015 (.0018) -.0115 (.0031) .0014 (.559) (.626) (.936) (1.34) (.0019) .694 .689 .689 .685 .687 Income Tax Liability of $80,000 (N=1396) Cutoff for a tax increase or decrease: DemDem*TaxComp RepRep*TaxComp Mixed*TaxComp R-squared $50 $100 $200 $400 Linear -.514 (.673) -2.39* (.684) -.675 .338 (.704) -3.15* (.729) -.334 .312 (.791) -2.93* (.899) .405 .017 (.955) -5.23* (1.09) -.308 -.0003 (.0006) -.0057* (.0016) .0008 (.544) (.591) (.626) (.785) (.0006) .686 .688 .686 .689 .687 Parentheses contain standard errors. Specification: Vt- NormalVoteji= $1DemDemjt*TaxCompjt + f 2RepRepjt*TaxCompjt + 3Mixedjt*TaxCompjt +pstate*year dummies+ a + Fj where V is the gubernatorial vote and DemDem is a dummy variable equaling 1 if both governors are Democrats and 0 otherwise. 30 Table 9: Total Revenues Results Broken Down by Party For the Incumbent's Party when He Does Not Stand for Reelection Total Revenues per capita (N=2062) Cutoff for a tax increase or $50 $100 $200 Linear .821 (1.13) -1.13 (1.28) 1.81 (1.22) .739 -1.54 (.779) .047 (.944) 1.52 (.837) .740 -.695 (.736) -1.17 (.866) 2.22* (.671) .741 .0115* (.0046) -.0206* (.0061) .0070 (.0044) .742 decrease DemDem*TaxCom p RepRep*TaxComp Mixed*TaxComp R-squared Parentheses contain standard errors. Specification: V\j- NormalVotejt= p1DemDemjt*TaxCompjt + f 2RepRepjt*TaxCompjt + P3Mixedjt*TaxCompjt +pstate*year dummies+ a + Cit where V is the gubernatorial vote and DemDem is a dummy variable equaling 1 if both governors are Democrats and 0 otherwise. RepRep is a dummy variable equaling 1 if both governors are Republicans and 0 otherwise. Mixed is a dummy variable equaling 1 if there is one Democratic governor and one Republican governor. 31 Ark Ixns .4 H190 'S MO TN LA 32

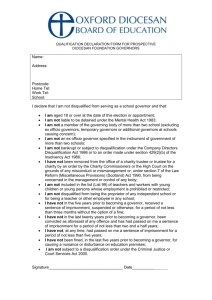

![Goal_3[1] All](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010010228_1-0ecebfdf213363f81a0a620c92dcd9d1-300x300.png)