A Guide to Maintaining the Historic Character of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence

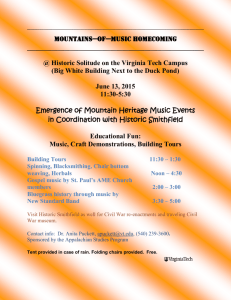

advertisement