Linking Housing and Public Schools in the HOPE VI

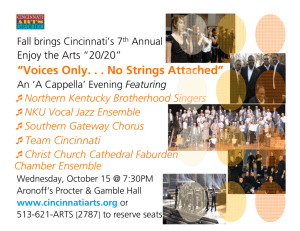

advertisement