Summary Report for 2010 Edna Bailey Sussman Internship Grant

advertisement

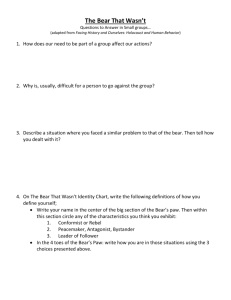

Summary Report for 2010 Edna Bailey Sussman Internship Grant Effect of Variable Mast Production on American Black Bear Reproduction and BearHuman Conflict in the Central Adirondack Mountains Courtney R. LaMere SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Summary of proposed work The purpose of this internship supervised by Mr. Jeremy Hurst of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) was to investigate the relationship between natural food cycles and black bear reproduction and nuisance behavior in the Adirondack Park. The DEC is tasked with the management of wildlife within the park, which includes an expanding black bear population. This population growth combined with an increasing number of human visitors has provided more opportunities for human-bear conflicts in the backcountry, campgrounds and hamlets. While it is believed that periodic increases in black bear-human conflict levels in the central Adirondack region are due to drought and lack of natural food sources, the degree of impact has not been quantified. Indices of hard and soft mast abundance may serve as indicators of potential bear nuisance activity and reproductive rates. Equipping wildlife managers with knowledge of these indicators would increase their predictive ability for population management and provide empirical evidence to support educational outreach to mitigate human-bear conflicts. In addition to diets of grasses and berries during the spring and summer, bears in this northern hardwood region rely primarily on beechnuts in the fall to maintain fitness through the winter. American beech follows an alternate-year cycle of crop failure. Females typically produce cubs every other year, and researchers in other areas have found synchronous reproduction with the beechnut crop. The objectives of my internship: 1) Assess patterns in production of natural bear foods in the central Adirondack Mountains from a 20-year dataset of forest fruit and beechnut abundance to identify periods of food abundance and food shortage 2) Identify patterns in Adirondack black bear reproduction from 20 years of DEC harvestby-age data to confirm reproductive synchrony with the beechnut crop cycle 3) Quantify the relationship of natural food shortages to bear mortality and nuisance bear movements 4) Develop recommendations for mitigation of human-bear conflicts based on observed patterns in food abundance and present a final report to DEC 1 C. LaMere 2010 Sussman Report My specific hypotheses were that nuisance behavior would increase in periods of natural food shortage and bear cub production would increase in the year following a successful beechnut crop. Narrative of work completed Beechnuts and Nuisance Complaints I obtained electronic files of nuisance complaint records from 1990 to 2003 from the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Adirondack Program (WCS) and records from 2005 to 2008 from the DEC. I used GIS software (ArcGIS 9.3.1) to determine the extent of agricultural land in and around the Park. Using the National Land Cover Dataset (NLCD) maintained by the USGS, I created a map showing locations of row crops and pasture/hayfields in northern New York. With the exception of the extreme eastern edge of the Adirondack Park that occurs in the Champlain Valley, the majority of the park has little to no agricultural land with row crops numbering much fewer than pasture and hayfields. In order to determine the range and importance of red oak and American beech in the region, I created maps using data from the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) plots maintained by the USFS. The USFS establishes 1 FIA plot per 6,000 acres and measures variables including tree diameter, height, and density. The USFS calculated importance values per plot for each tree species occurring in northern New York. Importance values are determined by adding together the relative frequency, density, and dominance for each species. The importance values for red oak are highest along the eastern and southeastern edges of the park and the highest importance values for American beech are distributed throughout the park. This series of maps allowed me to determine that using human-bear conflicts occurring inside the park boundary would be a practical way to target bears that did not rely heavily on row crops and acorns in their diet. While black bears will travel large distances (>20km) in search of food, using incidents occurring inside the park is a way of focusing my analyses on individuals whose main source of high-energy carbohydrates is beech mast. I also created a map showing the total number of nuisance complaints by town for the period of 2001 to 2008 (map at end of document). The majority of the nuisance behavior events used for statistical analysis occurred in the interior of the park, a considerable distance from agriculture and red oak mast. I removed incidents of bear complaints occurring outside of the Park boundary from the 1990 – 2008 data and used the year 2000 as a starting point for my statistical analysis because in 2000 a Standard Operating Procedures Manual (SOPM) was created that provided DEC staff in all regions with uniform guidelines on agency response to situations involving bears. Consequently, complaint records for the years following 2000 are more intact and provide a better index for comparison. The SUNY ESF Huntington Wildlife Forest (HWF) in Newcomb, New York has recorded qualitative fruiting phenology data on important bear foods since 1989. Fruit abundance is ranked annually on a scale from 0 (no fruit) to 4 (excellent). I compared black bear nuisance complaint records in the Adirondack Park with beechnut abundance rankings from HWF. 2 C. LaMere 2010 Sussman Report I used Statistical Analysis System 9.1(SAS) to perform a regression analysis on the beechnut abundance rankings from HWF and the bear complaint records occurring inside the Adirondack Park for the years 2001 through 2008. The results indicated that there is a significant negative correlation between the number of nuisance black bear complaints and beechnut abundance. This supports my hypothesis that human-bear conflicts increase in years with a beechnut crop failure. Alternate Food Cycles I identified important black bear food species in the central Adirondacks from previous research on bear food choices. With the exclusion of beech, there were 14 species of bear foods identified for which there were complete historical fruiting records from the HWF Adirondack Ecological Center’s Adirondack Long-Term Ecological Monitoring Program (ALTEMP). The common names for these species are red raspberry, blackberry, wild sarsaparilla, black cherry, pin cherry, chokecherry, apple, blueberry, serviceberry, winterberry, American mountain ash, nannyberry, beaked hazelnut, and arrowwood. For ease of discussion, I will refer to these other 14 identified bear foods as soft mast. I tested for a correlation between each of these soft mast species and nuisance black bear complaints in the Adirondack Park. As discussed above, a significant negative correlation was found between beech abundance rankings and nuisance bear complaints from 2000 to 2008. I used the Pearson’s coefficient to test for correlation and found that none of the other species had a significant correlation to the number of nuisance complaints recorded. Additionally, I used the average of the soft mast rankings per year to test correlation with the number of nuisance bear complaints, and found no significant relationship. I also tested for correlation between each of the soft mast species and the beechnut ranking using the same method for the time period 1990 - 2009. The only food species that was significantly correlated with the beechnut cycle was American mountain ash, which occurs sporadically in the region. However, when all 14 soft mast species rankings were averaged for each year they were in fact positively correlated with the beechnut cycle (graph at end of document). It appears that the soft mast species and American beech follow similar cycles of annual food production which is most likely influenced by weather patterns. Reproductive Synchrony I analyzed the black bear harvest- by-age data for the northern NY bear hunting zone, looking for evidence of synchrony in cub production. The beechnut crop in the region is on an alternating boom and bust cycle with crop failures typically occurring in an odd numbered year. I hypothesized that more cubs would be born in an odd numbered year following the successful crop of the prior even year. With the sample totals separated out by age class for the years 19802006, I was able to identify which harvested bears were born in an even versus odd numbered year. For example, an age class one bear (1.75 years old) that was harvested in the fall of an even numbered year was born in January or February of the previous odd numbered year. Additionally, an age class two bear that was harvested in an even numbered year was born in an even numbered year. I calculated the percentage of each age class in every year’s harvest sample. Using this method, I tracked the contribution of cubs born in even and odd years to the harvest sample and found an alternate year pattern with higher cub production occurring in odd 3 C. LaMere 2010 Sussman Report numbered years. On average, 60% of the bears in the sample were born in an odd numbered year and 40% were born in an even year. Additionally, I tested whether cub production was correlated to annual beechnut abundance rankings using the aged subsample of annual harvests. By finding the bear’s age at harvest and back-calculating to the year the individual was born, I used the beechnut crop ranking for the year before that birth year as the independent variable. The number of bears in the harvest from 1986 to 2007 born following that crop year was the dependent variable. For example, if there were 10 five- year-old bears harvested in 1995, I calculated that they were born in 1990. Using January as the month of birth, I referenced the beechnut crop ranking of the preceding fall of 1989 which was 0. Likewise I used the 1989 beechnut crop ranking for four-year-old bears harvested in 1994. The results indicate that cub production increases with increased beechnut production. Trapping and Monitoring One of the intentions of the internship was to aid DEC personnel in capturing and radio tracking collared bears in the central Adirondacks. Due to state budgetary constraints, research based trapping was not conducted in the summer of 2010. I assisted in the relocation and aversive conditioning of one nuisance bear, and focused my attention on setting up the logistics for a reproductive tract collection by bear hunters in the fall of 2010. This included creating a project website and conducting outreach to the hunting community, news outlets, and sportsman’s clubs participating in the project. Discussion of future work I presented my results describing the effect of beechnut crop failure and relative fruit abundance on black bear nuisance behavior and reproduction to regional DEC biologists on September 20, 2010. I developed recommendations for mitigation of human-bear conflicts and anticipating black bear harvest levels. 1. With the budgetary constraints that state wildlife managers face, it is important to focus outreach and monitoring effectively. My results indicate that the agency can anticipate summers with high levels of human-bear conflicts by monitoring the cycles of natural foods. Soft mast and hard mast species appear to be cycling in unison. Surveys of the foods available early in the season such as strawberry and pin cherry may predict the abundance of other summer foods and consequently the level of nuisance bear activity. The beechnut crop has been shown to be on an alternate year cycle. Tracking the crop of this important food source will also help predict the behavior of bears in the summer season. Anticipating summers with low abundance of natural foods will allow the agency to recruit volunteers and hire seasonal technicians in the years when they are most needed. 2. The DEC is tasked with managing bear hunting in the state and as such needs to anticipate harvest levels and bear movements during the hunting season. Upon request following my meeting in September with DEC personnel, I analyzed harvest rates during 4 C. LaMere 2010 Sussman Report the early hunting season (September 18 – October 15) and regular hunting season (October 23 – December 5) in northern NY. The early season occurs before the hard mast is available to bears and it is assumed that they are still feeding on soft mast species such as black cherry and mountain ash. The regular season occurs when beechnuts are accessible and bears are likely to find a stand of American beech and stay in the area. Soft mast species may require a foraging technique that includes larger, more variable movements by bears across the landscape, which can make it difficult for hunters to reliably locate the animals. My analyses indicate that as the soft mast ranking increases, the number of black bears harvested during the early season decreases and as the beechnut crop ranking increases, the number of black bears harvested during the regular season increases. The data collected and analyzed during this internship will be a central feature of my Master’s thesis. I have acknowledged the support from the Edna Bailey Sussman Foundation in all presentations and reports on this work, and will continue to do so in the future. 5 C. LaMere 2010 Sussman Report 6 C. LaMere 2010 Sussman Report 7