Limits of Acceptable Change and Natural When is it Not?

advertisement

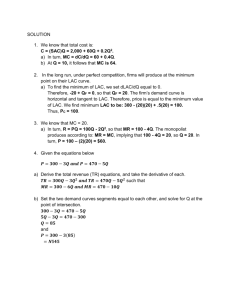

Limits of Acceptable Change and Natural Resources Planning: When is LAC Useful, When is it Not? David N. Cole Stephen F. McCool A Generic LAC Process __________ Abstract—Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) was originally formulated to deal with the issue of recreation carrying capacity in wilderness. Enthusiasm for the process has led to questions about its applicability to a broad range of natural resource issues—both within and outside of protected areas. This paper uses a generic version of the LAC process to identify situations where LAC can usefully be applied and situations where it cannot. LAC’s primary usefulness is in situations where management goals are in conflict, where it is possible to compromise all goals somewhat, and where planners are willing to establish a hierarchy among goals. In addition, it is necessary to write standards for the most important (constraining) goals—standards that are measurable, attainable, and useful for judging the acceptability of future conditions. In brief, the LAC process involves the following six steps. Refer to Cole and Stankey (this proceedings) for more detail and an illustration of how this six step process was used to deal with the recreation carrying capacity issue. Step 1. Agree that two or more goals are in conflict. The LAC process is fundamentally a means of resolving conflict. Goals conflict whenever it is impossible to simultaneously optimize conditions for all management goals. Step 2. Establish that all goals must be compromised to some extent. Step 3. Decide which conflicting goal(s) will ultimately constrain the other goal(s). In other words, a hierarchy of goals must be established. If there are multiple constraining goals, either these constraining goals cannot conflict with each other or it must be possible to establish a hierarchy among the constraining goals. Step 4. Write indicators and standards, as well as monitor the ultimately constraining goal(s). Indicators must be measurably and standards must be attainable. They also must be useful for judging the acceptability of future conditions. It is important to develop monitoring protocols and field test them to make certain that indicators can be measured. Step 5. Allow the ultimately constraining goal(s) to be compromised until the standard is reached. The process of balancing conflicting goals begins by allowing the most important goal(s)—the one(s) for which standards have been written—to be compromised somewhat. Standards define the maximum amount of compromise that will be tolerated. Step 6. Compromise the other goal(s) so standards are never violated. Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) and related processes have been widely embraced as innovative and useful frameworks for dealing with recreation management issues in wilderness (McCoy and others 1995). Consequently, there has been considerable enthusiasm expressed about applying these systems outside wilderness and to issues other than recreation. The utility of LAC-like frameworks outside wilderness has already been demonstrated. Development of the VERP process demonstrated that LAC concepts can be applied in the frontcountry of National Parks (Hof and Lime, this proceedings). LAC-type processes have also been used to deal with issues other than recreation, although these processes are seldom referred to as a LAC process. Given that LAC has been extended beyond recreational carrying capacity issues in wilderness, the question to address is under what conditions is the LAC framework useful and under what conditions is it not useful? To answer this question, it is critical to define the LAC process in more generic terms than Stankey and others (1985) did in their original formulation of the process. The workshop participants agreed that the generic process described in Cole and Stankey (this proceedings) represented the LAC process conceptually. Situations in Which LAC is Useful _________________________ By understanding the details of the process just outlined, it becomes easier to assess what conditions must apply if the LAC process is to be useful. By working through the six steps, it is possible to assess whether or not LAC is likely to apply in any given situation. As an example of a situation where LAC was useful, consider the approach adopted by local government in Missoula, MT, to deal with concern about pollution from wood burning stoves. The approach developed is fundamentally a LAC process, although it was not referred to as such and it deals with an issue other than recreation on lands outside wilderness. In: McCool, Stephen F.; Cole, David N., comps. 1997. Proceedings—Limits of Acceptable Change and related planning processes: progress and future directions; 1997 May 20–22; Missoula, MT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-GTR-371. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. David N. Cole is Research Biologist, Rocky Mountain Research Station, P.O. Box 8089, Missoula, MT 59807. Stephen F. McCool is Professor, School of Forestry, The University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812. 69 In Missoula, wood burning stoves are a popular method of heating houses. However, in the winter the city is prone to temperature inversions that trap cold air in the valley bottom. Pollution, in the form of excessive particulate matter, is a common problem when this occurs. Local government used a LAC-like process to deal with this situation. The six steps can be used as a framework for describing what they did. Step 1. The two goals that are in conflict are (1) allowing Missoulians to heat their homes with wood and (2) maintaining healthy air quality. Neither goal can be optimized without compromising the other goal. Step 2. The decision was made to compromise each goal to some extent. Alternatively, wood stoves could have been banned entirely (optimizing the air quality goal) or it could have been decided that wood burning would be allowed regardless of air quality (optimizing the goal of being free to use wood stoves). If either of these decisions had been made, a LAC-type process would not have been necessary. Step 3. The decision was made that maintaining healthy air quality would ultimately constrain freedom to use wood stoves. If such a goal hierarchy had not been established (if the goals of healthy air and freedom to use wood stoves were considered equally important), a LAC-type process would not have worked. Some other means of compromising between goals would have been necessary. Step 4. The indicator selected was amount of particulate matter in the air and a quantitative standard was written that prescribes a maximum acceptable level of particulate matter in the air. This indicator is measurable and the standard is attainable. Step 5. Missoula residents are allowed to use their wood stoves—and degrade air quality—as long as the particulate matter standard is not exceeded. Step 6. When the particulate matter standard is exceeded, or in danger of being exceeded, use of wood stoves is prohibited. This illustrates how the LAC framework is applicable to a number of issues other than recreation management. The first four steps of the generic LAC process suggest four conditions that must apply if the LAC process is to be useful. First, there must be at least two conflicting goals. Second, there must be a willingness to compromise all conflicting goals. Third, there must be a willingness to consider one or more of the conflicting goals to ultimately constrain other goals. Fourth, it must be possible to write measurable and attainable standards that quantify the minimally acceptable state of the ultimately constraining goal(s). Another requirement of standards—if LAC is to be used— is that they must be useful for judging the acceptability of future conditions. This should be possible in situations where the preferred conditions of the attribute for which the standard is being written is either unchangeable or subject to direct measurement. For example, in the case of concern about the invasion of exotic species in protected areas, the desired state of “no exotic species” will be as applicable in the future as it is today. Because this desired state is unchangeable, it provides a meaningful reference for any standard written to accept a limited degree of exotic invasion. A standard, such as “no more than 10 percent of the area occupied by exotic species,” is measurable, presumably attainable, and a meaningful basis for judging acceptability in the future. For many issues of concern, preferred conditions are relatively unchangeable. When the preferred conditions of an attribute changes over time, LAC standards can still be written as a maximum deviation between existing and desired conditions, if those conditions can be measured both now and in the future. For example, consider the case of standards to address recreation impact on vegetation at campsites. A meaningful standard cannot be written for vegetation cover on campsites, because the preferred vegetation cover is variable from year to year, as well as from site to site. Instead, a LAC standard can be written as “no more than 50 percent vegetation loss on any campsite.” This can be assessed by measuring vegetation cover on both campsites and neighboring undisturbed sites (indicative of conditions on the campsite prior to use). Although vegetation cover changes over time, the acceptable deviation between existing and desired conditions is constant. Such a standard will provide a meaningful measure for judging future acceptability. Standards based on deviations between impacted places and undisturbed reference sites should be possible to develop wherever impacts are localized, leaving some places undisturbed. Situations in Which LAC is Not Useful _________________________ The first four steps of the generic LAC process are also useful in identifying situations in which LAC is not useful. Step 1. If there is no conflict between goals, there is no need for a LAC process. In many recreation areas, for example, a common management goal is to have high quality interpretive displays. Attempts to maximize the quality of interpretive displays are not likely to conflict substantially with other goals of the recreation area. Consequently, LAC concepts do not help with that portion of recreation planning that deals with interpretive displays. For many aspects of recreation planning (for example, trail maintenance, sign policies, provision of toilets, and so on) there is little conflict between goals and, therefore, no need for LAC. The same is undoubtedly true of many nonrecreational situations. Where there is no conflict, planners should simply define desired conditions and implement management actions to progress toward that desired state. It might also be worthwhile to monitor progress and even to write a standard that defines minimally acceptable progress toward the desired state. However, such a standard is not a LAC standard. It is a management performance standard—not a standard defining a compromise between goals. Consequently, once minimally acceptable conditions are met, there is no reason not to implement actions to progress further toward the desired state. Step 2. If there is conflict between goals, but one of the goals cannot be compromised, a LAC process is not appropriate. For example, there may be situations where recreation use threatens prehistoric sites and there is zero tolerance of disturbance at these sites. In this case, the goals of allowing recreational access to prehistoric sites and avoiding disturbance of those sites are in conflict, but the site disturbance goal cannot be compromised. Many other examples exist— both in recreation planning and planning for issues other than recreation—where there is zero tolerance or ability to 70 Conclusions ____________________ compromise and, therefore, LAC is an inappropriate planning framework. In these situations, managers should state the desired condition for the goal not subject to compromise and do whatever is necessary to avoid compromising that goal. Step 3. If managers cannot establish a hierarchy of goals, in which some goals constrain others, LAC will not work. This hierarchy of goals is necessary because standards must be written for the constraining goal(s)—and this goal only. If standards were written for all conflicting goals it would create situations where one or the other set of standards would be violated and could not be brought back into compliance without violating the other standard. This is the reason standards were not written for managerial conditions in the original application of LAC to wilderness recreation, even though “unconfined” experiences are important in wilderness. Although it might be desirable for visitors to remote, near-pristine places to never contact a ranger patrol, it might be necessary for rangers to patrol these areas to keep them near pristine. If standards were written that prescribed both near-pristine conditions and lack of ranger contact, management would have to decide which standard to violate. In the original application of LAC to recreation management in wilderness, it was assumed that preservation of conditions should constrain managerial conditions as well as freedom of access and freedom from restrictions. Consequently, standards were only written for this most important goal—the preservation of natural conditions and solitude in wilderness. Step 4. Even for management issues for which there is conflict, room for compromise, and a hierarchy of goals, the LAC process can only be applied if it is possible to write measurable and attainable standards that quantify the minimally acceptable state of the ultimately constraining goal. Qualitative standards may suffice but only if it is possible for different individuals to agree on whether or not standards are being violated. We simply do not have the experience to judge whether qualitative standards are totally unacceptable or merely inferior to quantitative standards. As noted earlier, LAC standards do not appear to be useful in situations where the desired state of the attribute for which standards are to be written is both changeable and impossible to measure. This is a common situation where the issue of concern is the effect of a pervasive (as opposed to localized) threat on natural ecosystems. For example, we might wish to limit the adverse effects of air pollution on tree growth rates by writing a LAC standard limiting declines in tree growth rates. However, we know that desired tree growth rates in the future will differ unpredictably from those that exist today, due to natural climatic oscillations. Moreover, desired growth rates (those occurring in the absence of air pollution) will be impossible to measure because all trees will be affected by air pollution in the future. This leaves us with a few options for developing standards, but all options have drawbacks. Refer to Merigliano and others (this proceedings) for further discussion of these options. We conclude that the LAC process has widespread applicability to issues other than recreation management and in places other than protected areas. In protected areas, LAC can be useful in dealing with management of a range of threats to resource conditions that can be considered either desirable or acceptable as long as they do not cause too much impact. LAC may be even more widely applicable outside protected areas than within protected areas. Outside protected areas, naturalness is not such a critical goal. Consequently, it is more acceptable to define standards in static terms and be content to achieve those conditions. However, because there may be much less agreement about goals and their relative importance (Brunson, this proceedings), LAC may be more difficult to implement outside protected areas. We also conclude that the LAC process is not a useful framework for dealing with all of the issues that must be dealt with in wilderness and park recreation management planning. Many recreation management and visitor experience quality issues do not involve conflict or compromise. Examples include the quality of interpretive displays, trail maintenance levels, or the effects of intentional exotic species introductions. Other issues, such as the impacts of recreation on wildlife, do involve conflict and compromise, but the utility of LAC is limited by the apparent impossibility of writing meaningful quantitative standards. The LAC process should be thought of as a framework for dealing with certain issues that are frequently confronted in the planning and management process. Those issues to which it applies are the particularly sticky issues that require conflict resolution. The LAC process provides a framework for working collaboratively to explicitly define a compromise between conflicting goals. In attempting to decide whether LAC is an appropriate process to use, it might be helpful to answer the following questions: 1. Am I attempting to resolve conflict between several goals? 2. Am I willing to compromise all goals to some extent? 3. Am I willing to establish a hierarchy of goals—decide that some goals will constrain other goals? 4. Is it possible to write measurable and attainable standards that can be useful for assessing acceptability in the future? The LAC framework, as currently formulated, should be useful if—and only if—all four questions can be answered in the affirmative. References _____________________ McCoy, K. Lynn; Krumpe, Edwin E.; Allen, Stewart. 1995. Limits of acceptable change: evaluating implementation by the U.S. Forest Service. International Journal of Wilderness. 1(2): 18-22. Stankey, George H.; Cole, David N.; Lucas, Robert C.; Petersen, Margaret E.; Frissell, Sidney S. 1985. The limits of acceptable change (LAC) system for wilderness planning. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-176. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 37 p. 71