C l r

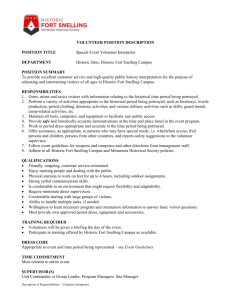

advertisement