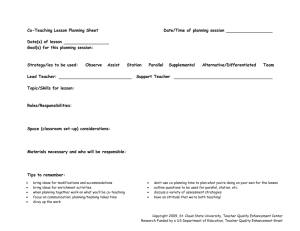

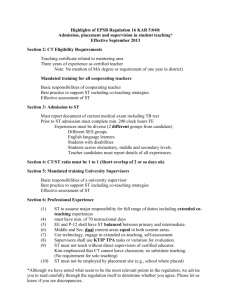

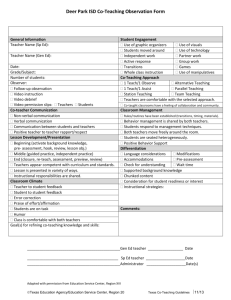

Mentoring the Student

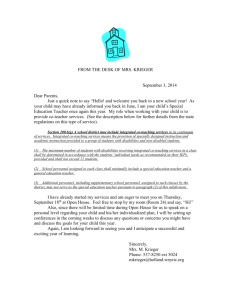

advertisement