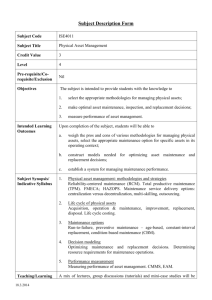

Research Michigan Center Retirement

advertisement