Trends in the Composition and Outcomes of Young Working Paper M R

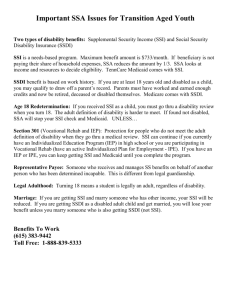

advertisement