Declining Wealth and Work among Male Veterans Working Paper

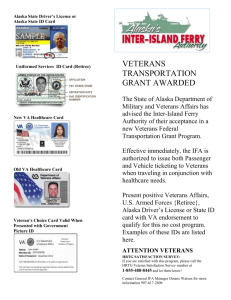

advertisement