GROWING MICRO AND SMALL ENTERPRISES IN LDCs

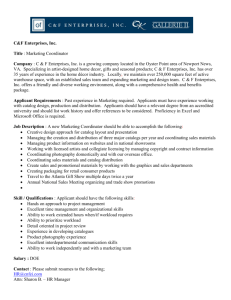

advertisement