NATIONAL MENTAL HEALTH REFORM

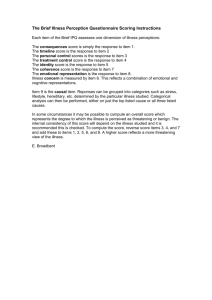

advertisement