MAKING SENSE OF THE SENSES ... THE WONDER HORMONE GENETICS...

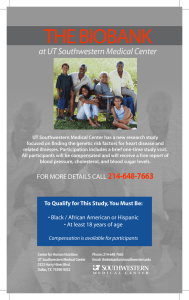

advertisement