Document 10398006

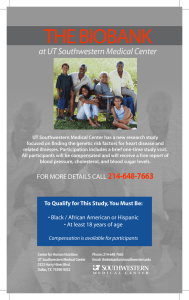

advertisement