A R 2 0 14 N N U A L

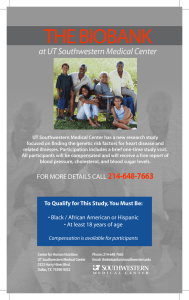

advertisement