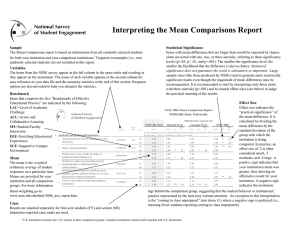

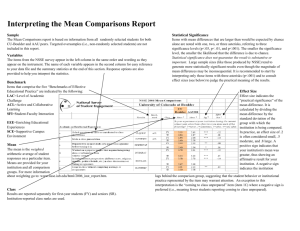

BRINGING THE INSTITUTION INTO FOCUS ANNUAL RESULTS 2014

advertisement