PSYCHOLOGY AND THE DESIGN OF LEGAL INSTITUTIONS Montesquieu Lecture 2007

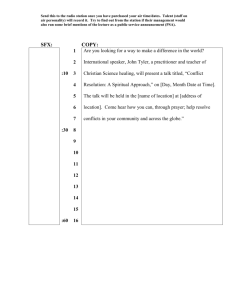

advertisement