Community Index 2013 Greater New Haven

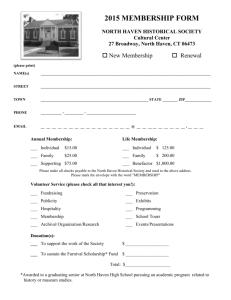

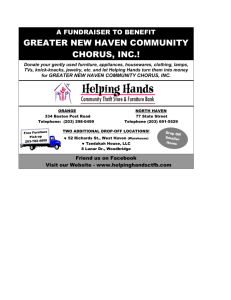

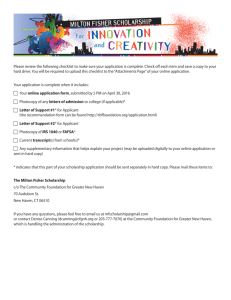

advertisement