ANALYSIS AND HIGHLIGHTING OF LESSONS LEARNT PROGRAMME

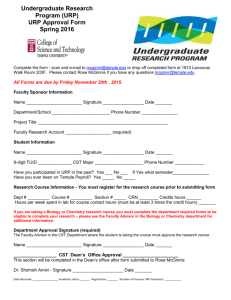

advertisement