Equity Financing CHAPTER

advertisement

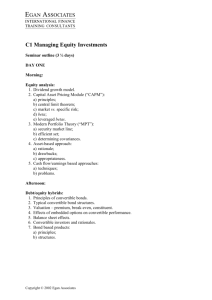

© Commodity Research Bureau 1977 www.crbtrader.com CHAPTER Equity Financing In the preceding chapter the processes by which risks of losses resulting from changes in price are shifted from one group of people to another were described. It is clear that the need to shift risks was the original impetus for the development of the markets and that, for more than a century, hedging of price risks has been the dominant force in determining the size of the markets and the fluctuations in the level of trading. However, this description does not explain why the activity takes place; why some businessmen involved in commodity production, marketing, and use have a compulsion to hedge risks while others do not. To observe the practice is useful and adequate for understanding the past and present. It is necessary to inquire into the motivations of hedgers and the institutional arrangements lying behind the hedging activity if we are to fully understand the why of that which has taken place and to make progress in charting the course that lies ahead. Financial Instrument A futures contract is a financial instrument and futures trading is a financial institution engaged in gathering and using equity capital. It is not a financial institution in the sense of a bank in which money is received from one group of people and loaned to another. Rather, it is a means by which loans made by banks or operating money otherwise secured by businesses is guaranteed against loss. When bank loans, or capital from any other source, can be protected from part or all of potential losses they are more readily forthcoming than when they cannot. Operating businesses acquire debts that they add to their own net worth to build a total operating capital structure. By this process, they can control capital without owning it and the people from whom they obtain funds can own 130 © Commodity Research Bureau 1977 www.crbtrader.com Equity Financing 131 capital without administering its use. The financial system is the means by which the ownership of real capital is separated from its control. Futures markets are a part of the system. In this context, a futures contract is the exchange of a monetary obligation, or debt, for a commodity obligation, or debt. The long speculator exchanges his own monetary obligation to pay for the commodity for the obligation of the hedger to deliver the physical commodity. The short speculator exchanges a monetary obligation to buy and deliver for the commodity obligation of the hedger to accept and use the commodity. Thus, the hedgers remove themselves from financial debts by substituting commodity debts for them. The financial obligations are assumed by the speculators. This process of debt exchange through the financial system enables resources to be used more productively and it is from this that the social benefits of the financial system flow. The consolidation of resources through the exchange of debt enables increased productivity associated with large scale enterprises. The ownership of scarce resources is widely diffused and, if it were not possible to consolidate their control, production would be quite as diffused as ownership. This would result in small-scale production, limited technological advance, and less total productivity. Control of capital needs to be consolidated into the hands of the people who can use it most efficiently and people who can operate businesses most efficiently need access to capital beyond their own equity. In the last chapter we tended to look on speculators as the people who accommodated the hedgers in a null fashion, appearing when and only as needed. As we turn to borrowing money from banks to finance stored inventories, we tend to merely note that warehousemen who have their inventories hedged can borrow more money than those who don't. This does not do justice to the speculator. By committing his wealth to commodity futures he influences the warehousing activity and its cost, and, thus, becomes an important financier. Financing Process The process by which equity capital is raised through futures trading can best be seen by some examples. First, the importance of hedging in financing stored inventories of grain has long been recognized. Terminal elevator operators, cotton merchants, grain processors, and, to a lesser extent, country grain warehousemen are often able to borrow in excess of 90 percent of the value of stored commodities at prime rates of interest, providing the inventories are offset by short positions in futures markets. Warehouse receipts serve as collateral for the loans so that the general balance sheet and liquidity of the company are not affected by the inventory ownership except for the small difference between the value of the cash commodity and the amount of the loan. In some cases in which the capital position of the company is so fully extended before borrowing to buy inventory that the commodity loan would restrict financing of noninven- © Commodity Research Bureau 1977 www.crbtrader.com 132 The Economics of Futures Trading tory activities, separate warehouse companies are established or a system of field warehousing is used. In such cases the commodity inventory does not enter the balance sheet. The inventory loans are sometimes worked up to quite high levels. Banks frequently loan the margin deposit on the futures transactions as well as a high proportion of the current value of the inventory. Or, they loan the full value of the inventory on the basis that the margin deposit is quite enough protection. As we shall see when we consider hedging operations, the value of stored commodities tends to increase in relation to the futures price as the storage season progresses. For example, corn in country locations may sell 40 cents under the July futures price at harvest and typically sell for 5 cents under the July on July 1. There is thus a highly probable 35 cent storage profit in a hedging operation. Armed with this information, the country elevator operator may go to his banker and ask for the full purchase price of the corn, the margin requirements, and a part of the storage earnings and thus finance part of his operating costs in addition to the inventory. Bankers are not inclined to go so far, but the operator may get away with the full purchase price and margin plus a promise of the storage earnings as they accrue. As time passes the price of the commodity, hence, the market value of the warehouse receipts, changes. If the price goes down, the bank, reasonably, wants part of its money. It is readily available out of the increased value of the short futures position. The warehouseman asks his commission futures merchant for the money the bank wants. If the price goes up, the short futures position shows a loss and the commission house calls for margin. The value of the warehouse receipts has increased and the additional margin is forthcoming from the banker. The point of this is that ordinary bank financing is readily available for purchase and storage of hedged inventories. This is not the case for unhedged inventories. The transaction is put on the balance sheet and a normal liquidity margin is required. The proportion of the loan may be sixty percent or so-—certainly, a great deal less than for hedged inventories. The equity capital that the operator must furnish is very much less for hedged than for unhedged inventory. The uncertainty of the warehouseman's return is reduced by hedging but the total uncertainty of the venture is not. The fact remains that the market value of the commodity may decline so that the return to storage may be less than zero or it may increase so that the return is much more than the cost of storage. Commodity price variations are great relative to the cost of storage. Losses are taken out of someone's equity and gains are paid into someone's equity. As we have seen, on the other end of the hedges stand the speculators. The flow of funds from commission house to warehouseman to bank or from bank to warehouseman to commission house as prices decline or increase, flows further to the clearing house and from then on to the speculators, decreasing or © Commodity Research Bureau 1977 www.crbtrader.com Equity Financing 133 increasing their equity. The speculator is thus a financier, furnishing the equity capital required to absorb changes in price level. This process of financing is roundabout and specialized. It would be theoretically possible for the warehousemen to go directly to individuals for the money, selling them warehouse receipts and charging them storage. The individuals would, in turn, go to banks and borrow, on the basis of their net worth, the money to buy receipts. It would be a clumsy system with banks making many small loans to speculators instead of a few large loans to hedgers (note the relative size of positions of hedgers and speculators shown in Chapter 6 ) . More importantly, it would have little attraction to speculators because they would be furnishing the total of the funds rather than the equity necessary to finance price variations. Further, it is difficult to visualize such a scheme sufficiently sophisticated to afford liquidity comparable to that of futures trading. More likely, the warehousemen would reorganize the financial structure of their businesses in a way that would make the assumption of equity financing possible. As developed in Chapter 4, futures markets originated out of a need by country merchants for equity capital just as egg warehousemen turned to their friends for the equity capital to carry inventories. It is worth noting they did not necessarily lack the net worth to obtain funds from the banking system; in the case of eggs, net worth was more often adequate than not. They simply preferred not to endanger their capital structure to the extent they judged the price risks of a full inventory would endanger it. The system evolved over a long period of time as the most attractive among the alternative ways of gaining access to equity capital. A second example relates to cattle feeding. The production of market beef is a two stage process. The animals are raised from breeding herds on the grazing lands of the west and south and moved into specialized feeding yards or on to grain producing farms for further growth and fattening. The traditional pattern was from the forage producing lands of the plains and mountain states to the corn production lands of the central states, particularly Iowa and Illinois, and then on to the central markets for slaughter and shipment to eastern consumption markets. The farmers buy feeder cattle, feed them grain and other concentrates, and sell them for slaughter. Their profits and losses depend on their skills in feeding cattle and on the price of fat cattle in relation to the cost of feeder cattle and the cost of feed. The feeding process takes time (up to 12 months and an average of about 6) and the price of fat cattle fluctuates over wide ranges. Thus, cattle feeders are exposed to substantial amounts of risk unless they develop some kind of a risk shifting program. In this traditional feeding process, the farmers are part cattle feeder and part cattle speculator. Some follow the same pattern, year in and year out, buying the same size and quality of feeders at the same season each year and feeding them to © Commodity Research Bureau 1977 www.crbtrader.com 134 The Economics of Futures Trading the same weight and quality for sale. For these people, variations in the feeding margin average out over a number of production cycles so that, in the long run, they get the industry average returns (plus or minus their own technological skills in relation to those of the industry). But the long run may be several years so that a large reserve of equity capital is necessary for survival. These people are speculative nulls. Most cattle feeders, however, vary their operations on the basis of existing and expected prices and price relationships, becoming active participants in the speculative game. They buy different sizes, kinds, and qualities of cattle and sell at different weights and qualities in different production cycles. At times, they leave their lots empty and sell part of the feed supplies that they have produced on their farms, and at other times, they increase the size of their operations and buy additional feed. The extent to which programs are varied differs greatly within the cattle feeding fraternity. Some of the members are more speculator than feeder. In the main, the equity base of the traditional, midwest cattle feeders is large enough that they can readily absorb the risks associated with the business and can command the necessary capital to finance the operations. Starting in the latter 1950's the industry changed rather dramatically. Beef production nearly doubled from the early 1950's to 1975. Part of the increase was the result of increasing cattle numbers, but a substantial part of it was the result of putting more cattle through the feeding process so that slaughter weights were increased. Many of the small feeding operations went out of business. Large scale, commercial feedlots were developed. By 1968, the proportion of cattle fed in the traditional, small operation had decreased to about one-half and the other half was fed in commercial feedlots (1,000 or more head per year). Nineteen of these fed more than 32,000 head per year. The heaviest concentration was in yards of 8 to 32 thousand. The increase in scale resulted in a new set of risk and financing problems. The equities of the firms would not support risks associated with price variability nor did the firms want to take as large risks as they could. The practice of custom feeding developed, in which the cattle are owned by someone other than the feedlot and the feedlot is paid per pound of gain or feed cost plus overhead. The risking-financing activities are carried by .someone other than the feedlot. The cattle owners are speculators. By the late 1960's, approximately one-half of the cattle on feed in commercial feedlots were custom fed. The cattle custom fed are owned by ranchers, cattle feeders, meat packers, livestock marketing agencies, and investors. Many of the cattle feeders and investors use the operation in part as an investment and in part as an income tax shelter. They obtain leverage by borrowing from banks. The price of cattle followed a generally upward path from $25 per hundred weight in I960 to an average of $36 in 1972 and to a peak of $60 in the summer of 1973. The investors pyramided successfully. The price of cattle collapsed in 1973. The in- © Commodity Research Bureau 1977 www.crbtrader.com Equity Financing 135 ventory value of all cattle and calves in the U.S. decreased from $40 billion on January 1, 1973 to $20 billion on January 1, 1974. Heavy losses were taken and many loans could not be repaid to banks. The tax shelters work well in the context of tax avoidance, but poorly in the context of preserving income. It was in this context that futures trading in live cattle was started in 1964. It grew rapidly to an average open interest of 18,265 contracts of 40,000 pounds each (38 fat cattle) in fiscal 1968-69. The average open contracts and reported short hedges were: Fiscal Year Open Interest Short Hedges 1968-69 1969-70 1970-71 1971-72 1972-73 1973-74 1974-75 18,265 21,564 13,638 18,752 28,217 32,830 26,434 6,982 4,839 3,709 4,233 8,494 7,827 11,320 The impact of the price decline of 1973-74 is readily apparent in the increase in short hedges. The feedlot operators shifted from individual investors to the futures market as sources of equity capital. The bankers were a strong force in the shift. When their loans to feedlot operators are secured by futures contracts, they avoid the credit risks that were troublesome and in some cases, ruinous, in 1973-74. The equity capital is furnished by the speculators in futures markets. Pyramiding of Capital The command of resources can be greatly increased by hedging inventory risks or by pricing finished product before operating costs are committed. A loan rate of 90 percent on hedged inventory enables a firm with $1,000 of equity capital to contract and use, in a storage and merchandising activity, $10,000 worth of a commodity. A loan rate of 60 percent is two thirds as much, however, it enables the control of only $2,500 of inventory. Thus, the increase in the borrowing rate from 60 to 90 percent enables the control of four times as much capital. This is illustrated here at a 60 to 90 increase so that the numbers remain finite. As we have seen, a 60 to 100 increase is feasible in which case the equity capital requirement for price protection is zero and the multiplier is infinite. Constraints on the growth of the business are from sources other than equity capital for inventory control. The impact of equity financing through fixing sales prices of products ahead of production is equally impressive. Suppose that a corn producer is operating 1,000 acres and is contemplating expanding to 2,500 acres by leasing additional land. His lease cost is $100 and his operating cost other than return on fixed investment in machinery and equipment is $100 per acre, his anticipated yield is © Commodity Research Bureau 1977 www.crbtrader.com 136 The Economics of Futures Trading 100 bushels, and the net price that can be obtained is $2.50 per bushel. He thus has a prospective operating margin of 50 cents or a total of $125,000 compared to a current $50,000. He will use up virtually all of his balance sheet, liquidity in the purchase of additional equipment. He has to furnish a bank guarantee for payment of the lease. How much of his own equity must he hold for operational costs ? It depends on the percentage loan. Price vulnerable, the bank may loan 60 percent, requiring $100,000 of operator equity but not price vulnerable the bank may go 90 percent, requiring only $25,000. This latter amount is not really a price vulnerability equity but rather a guarantee of the organization and management skills of the operator in the production process—his technical ability. If his past performance record is excellent, the bank may loan the whole of the operational cost and the lease guarantee. The ability to obtain the operating capital is not the only consideration in fixing sales prices. It protects the operator from his own mistakes. The market may not offer a price as high as $2.50, making the expansion less attractive or possibly unprofitable. The operator may optimistically—as is the nature of farmers—expect the price to eventually turn out to be $2.50, commit his own equity, and fail. If the futures market won't furnish the equity and he can't otherwise obtain it, he the operator, is protected. More importantly, the process protects the equity capital of the operator. He may not elect to make the expansion if it must be done at the hazard of his equity. He may be willing to hazard his net worth on his ability as a corn producer but not as a corn speculator, especially if he recognizes that he is tied to the long side of a speculation with no flexibility. He would be long 250,000 bushels of corn, throughout the production period and thus a speculator on the price of corn. The old 100,000 bushel level may be more attractive. If this is the case, the expansion may not be made. Equity capital from futures markets may affect the business structure and efficiency of corn production. This is but one example. Others can be drawn from all commodities actively traded. Attraction of the Speculator There is something ridiculous about explaining to a chemist or a private detective that he, fine and noble entrepreneur, is furnishing the equity capital to feed cattle or produce plywood. Told, he is apt to reply, "Who, me? I'm just trying to make a fast buck in a market where I can get high leverage on money that I am willing to lose (heaven forbid)." Shades of Adam Smith's invisible hand. This process of equity capital flow from speculative markets is an example of commercial specialization among financial institutions. The process of gathering up money is separated from hazarding equity. One is the business of the banking system while the other is that of speculators. © Commodity Research Bureau 1977 www.crbtrader.com Equity Financing 137 The division and specialization is the thing that attracts speculators. Had they to furnish the whole of the operating capital to produce corn or buy feeder cattle there would be little attraction. They are only interested in furnishing the equity and taking the risks. A high proportion of commodity inventories for which futures markets exist are hedged. But only a small part of the production of corn, cattle, plywood, orange juice, etc. are forward priced in futures markets; the equity capital is otherwise forthcoming. How good the futures system is compared to others is a question that can only be answered after more of market operation has been considered. As we proceed, we will note that the cost of equity capital is very near zero and more likely negative than positive. A zero or negative interest rate on high risk capital compared to a bank interest rate on nonrisk capital is an interesting anomaly. Such is the behavior of speculators.