Adrienne Hosek Kate Pomper

advertisement

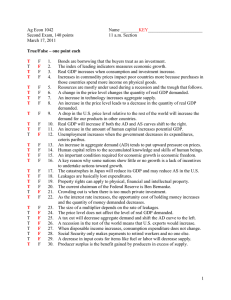

Adrienne Hosek Kate Pomper The Debt: Australia’s New Ball and Chain? Over the 1990s, Australia grew faster than any other large developed economy.1 Today, growth continues to be strong, and major economic indicators are positive. High debt, a housing bubble, and a steadily growing current account deficit, however, leave Australia vulnerable. To this end, we recommend tax incentives to encourage consumer saving, and otherwise, staying the course. I. Recent Macroeconomic Performance Australia’s economy is currently in its thirteenth year of expansion. This remarkable growth period can largely be attributed to low interest rates and inflation targeting, which have created a favorable climate for investment. Throughout expansion, unemployment has steadily declined. Gross Domestic Product Since 1992, Australia’s real gross domestic product has increased from 470.1 billion Australian dollars (2000) to 739.4 billion Australian dollars (2000).2 It has grown at nearly 4 percent on average and only grown at less than 3 percent in 2001, when the United States, Japan, Europe, and Australia’s partners in East Asia were in recession. The growth rate measured on a per capita basis is slightly lower, averaging 2.5 percent from 1992 to 2003, but trends consistently with the percentage change in real GDP. Interest Rates Between 1989 and 1992, two successive fiscal contractions and modestly expansionary monetary policy led interest rates to fall from 15.7 percent to 6.1 percent (Figures 1 and 2). Where interest rates averaged 12.4 percent in the decade preceding the contractions, they averaged 4.4 percent in the decade following. Inflation In 1993, the Reserve Bank of Australia introduced an inflation target with the objective of keeping monetary policy in check and preventing distortions in economic decisions.3 Since 2003, it has defined the target as 2-3 percent on average over the business cycle, as opposed to hard-edged band.4 This allows the Reserve Bank to employ monetary policy to soften fluctuations in the business cycle.5 1 “Down wonder; The Australian Economy,” The Economist, April 6, 2002. All statistics in this paper are from IMF International Financial Statistics, unless otherwise noted. 3 About Monetary Policy, Reserve Bank of Australia, available at http://www.rba.gov.au/MonetaryPolicy/about_monetary_policy.htm. 4 Ibid. 5 Ibid. 2 Since the target was implemented, inflation has averaged 2.5 percent per year. The Reserve Bank has not abstained from monetary policy, but rather, has managed it carefully. Between 1993 and 2004, the Reserve Bank substantially expanded the money supply only twice: it appears once to mitigate the effect of the Asian crisis and once to mitigate the effect of the international recession at the beginning of this decade (Figure 3). Each time, it carefully limited growth in the money supply the subsequent year to below GDP growth. In 1997, after the larger of the two expansions (32.4 percent) the Reserve Bank actually contracted the money supply. It additionally contracted the money supply in 1999. Investment and GDP Growth The combination of low interest rates and low inflation has led investment to grow rapidly. Excepting the Asian crisis and the international economic slowdown in 2000-2001, real investment has risen at a rate of 10 percent on average. Consistent with the IS-LM model, this has resulted in rising output. Importantly, monetary policy aimed at tracking GDP growth in the mid-1990s and buffering against recession later kept interest rates low with growth. Low interest rates and inflation targeting thus appear to explain much of Australia’s sustained economic expansion. Investment is the only component of GDP that surpassed the growth in real GDP consistently and substantially over the past thirteen years (Figure 4, net exports not shown). Significantly, consumption, the only component of GDP that exceeds investment, bolstered the economy in 1997 and 2001 when investment faltered because of recessions among Australia’s trading partners—the United States, Europe, and East Asia (Figures 4 and 5). Unemployment As GDP has grown, unemployment has fallen, illustrating Okun’s Law well (Figure 6). In 1992, the unemployment rate was 10.5 percent. By 2004, unemployment was 5.5 percent. While unemployment has decreased, labor force participation has risen slightly to 64 percent.6 This statistic, however, masks a decline in men’s labor force participation and a rise in women’s labor force participation. Women are more than twice as likely to work part-time.7 Consequently, 27 percent of employees in Australia in 2002 were part-time workers, as compared to 13 percent in the United States.8 II. Vulnerabilities in the Australian Economy Consumption As discussed above, consumption buoyed the Australian economy as recession threatened. Consumers continued to spend, encouraged to borrow by low interest rates and feeling “wealthy” 6 “Labor force participation: international comparison,” Australian Bureau of Statistics, available at http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4408BF5064F2EA02CA256E15007513BC. 7 Ibid. 8 Ibid. as housing prices skyrocketed.9 These very factors that allowed Australia to escape recession in the 1990s, however, may be the cause of recession this decade. Consumer borrowing increased so much over the 1990s that the ratio of per capita consumer debt to per capita income doubled, rising from 24.5 percent in 1992 to 52.7 percent in 2003.10 A hike in interest rates making debt more expensive could easily lead consumption to dive. A fall in housing prices could also cause a severe consumption shock. Housing prices are estimated to be overvalued by as much as 30 percent, and currently, over 60 percent of Australians are homeowners.11 The Debt At more than fifty percent of GDP, Australia’s total debt is one the largest of any industrialized country. Low interest rates and inflation, combined with a robust economy have allowed Australia to finance its growing debt through net borrowing from abroad. Since 1990, total debt has increased at an average rate greater than real GDP, though its movement has been volatile relative to that of GDP.12 The only way to sustain such debt is if the real growth rate of output is greater than the real interest rate. Up until this point, low interest rates have supported consumer and corporate spending habits. For the moment interest rates and GDP are moving in tandem, but interest rates could rise in the future (Figure 7). Slowing net foreign investment within the past two years indicates that foreigners are less confident output will continue to outpace interest rates in the future. This hesitance is support by evidence that foreign investors are beginning to favor more liquid investment instruments and have recently shied away from long-term interests. Current Account Deficit The changing investor environment is most aparent in the market for foreign goods and services. The current account deficit ballooned to $95 billion at the end last year, a 400% increase since 2002 (Figure 8). The deficit was largely driven by the favorable exchange rate, which made foreign goods relatively less expensive. As a result, Australian demand for foreign goods accelerated over these past two years, outpacing growth in demand for exports. An influx in foreign financial investment has financed the growing current account deficit. Starting in the first quarter of 2004, however, the financial account surplus narrowed considerably to half of what it was in 2003 and the overall balance of payments went into a $44 billion deficit, the second largest ever recorded. The largest balance of payment deficit occurred in 2000, in response to the global economic recession. 9 “House of Cards,” The Economist, May 29, 2003 [hereinafter House of Cards]. Reserve Bank of Australia Statistics, Table D05: Bank Lending Classified by Sector, available at http://www.rba.gov.au/Statistics/Bulletin/D05hist.xls. 11 See House of Cards. 12 Reserve Bank of Australia Statistics, Table H05: Australia’s Net Foreign Liabilities; IMF International Financial Statistics. 10 A closer look at the drop in total foreign investment reveals an interesting trend in the financial account that has significant consequences for Australia’s ability to sustain a trade deficit into the future (Figure 9). The financial account is divided into three main types of foreign investment: net direct foreign investment, net portfolio investment, and net other investment.13 Direct foreign investment generally signals long-term foreign interest in domestic enterprise, while portfolio investment includes shorter-term investments in Australian financial markets by foreigners. Other investments include transactions in currency and deposits, loans, and trade credits. Portfolio investment reacts more to short-term fluctuations in the economy making it highly volatile. Investors often prefer portfolio investment to direct foreign investment, because they can quickly pull-out in response to unfavorable changes in the exchange rate, interest rate and inflation. The financial account surplus in recent years has been solely supported by foreign portfolio investment. Two significant drops in net foreign and other investment, however, cut the financial account surplus in half in 2003. This narrowing combined with the expanding current account deficit led to the dramatic drop in the balance of payment curve during this time period. The last major balance of payment deficit occurred in 2000, and like the most recent event it followed a period of surplus fuelled by robust financial foreign investment. The earlier slump coincided with the global economic recession, which saw worldwide investment fall. Australia’s strong economic growth, however, quickly enticed foreign investors to reinvest in the Australian markets. In the period that followed, net portfolio, foreign, and other investment tended to be positive. At the same time, the current account deficit was smaller than in past years. The present situation is much different. Australia’s current account deficit has steadily grown, reaching historic proportions. This growth has been largely offset by foreign investment up until recently. Since 2003, however, the flow of funds from abroad has slowed as investors abandoned long-term interests in favor of short-term investment instruments. While net portfolio investment remains strong, net direct foreign and other investment has weakened; a signal that investors may believe Australia’s phenomenal growth is coming to and end. As the current account deficit grows, it will place increasing strain on the Australian economy, dampening expected GDP growth in upcoming years. III. Policy Recommendations ▪ Encourage consumer saving through the provision of tax incentives Increasing consumer saving would leave the economy less vulnerable to a consumption shock by decreasing consumers’ exposure to a hike in interest rates. More importantly, according to the Solow growth model, it would promote higher steady-state per capita GDP. Higher savings rotates the savings function outward leading to higher steady-state per capita capital (Figure 10). Though it is unlikely that Australia’s economy presents increasing returns to scale, it is important to note that if an endogenous growth model did provide a better fit, increasing savings would be 13 We do not mention foreign derivatives, as it did not appear to a significant impact on the financial account. less important. Given Australia’s expansion, it would already be on the portion of savings function where per capita capital and output are continually increasing (Figure 11). ▪ Do Nothing Australia has minimized the pressures of a growing debt by engaging in conservative fiscal and monetary policy. President John Howard is committed to reducing the government debt, and together with the parliament has avoided deficit spending in recent years. Monetary policy is constrained by inflation-targeting laws that require the Reserve Bank of Australia to keep inflation around two percent a year. The government should stay the course and avoid taking drastic measures even if it means Australia falls into recession. A more interventionist policy is unpredictable and may potentially lead to a worse outcome in the long-run. It is possible that Australia’s economy will continue to grow at a rate that can sustain its debt. Otherwise, a recession would allow Australia’s economy to naturally readjust to a point where it is in equilibrium and can resume growth under more stable conditions. Figure 1. Changes in Real GDP, Real Investment, the Money Base, and the Deposit Rate: 1985-1995 20.0% 15.0% 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 -5.0% -10.0% -15.0% -20.0% Changes in Real GDP Changes in Real Investment Changes in Money Base Deposit Rate Source: IMF International Financial Statistics Figure 2: IS-LM 1990-1992 r LM1 LM2 LM3 r1 r2 IS1 IS2 IS3 r3 Y1 Y3 Y2 Y Figure 3. Changes in Real GDP and the Money Base: 1989-2004 35.0% 30.0% 25.0% 20.0% 15.0% 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 -5.0% -10.0% -15.0% Changes in Real GDP Changes in Money Base Source: IMF International Financial Statistics Figure 4. Changes in Real GDP, Consumption, Investment and Government Spending: 1992-2004 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 0.0 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 -5.0 Changes in Real GDP Changes in Real Consumption Changes in Real Investment Changes in Real Government Spending Source: IMF International Financial Statistics Figure 5. Components of GDP, 2004 Real Net Exports (-), 3% Real Government Spending, 18% Real Consumption, 60% Real Investment, 25% Source: IMF International Financial Statistics Figure 6. Australia and Okun's Law: 1992-2004 Percentage Change in Real GDP 6.0% 5.0% 4.0% 3.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.0% -1.5 -1.0 -0.5 0.0 Change in Unemployment Rate 0.5 1.0 1.5 Source: IMF International Financial Statistics Figure 7. Interest v s Real Growth (GDP) Rate Millions Figure 8. Australian Balance of Payments: 1990-2004 15000 10000 U.S. Dollars 5000 0 -5000 -10000 -15000 Q1 1990 Q1 1991 Q1 1992 Q1 1993 Q1 1994 Q1 1995 Q1 1996 Current Account Q1 1997 Q1 1998 Financial Account Q1 1999 Q1 2000 Q1 2001 Overall Balance Source: IMF International Financial Statistics Q1 2002 Q1 2003 Q1 2004 Millions Figure 9. Financial Account (1990-2004) 20000 15000 U.S. dollars 10000 5000 0 -5000 -10000 -15000 Q1 1990 Q1 1991 Q1 1992 Q1 1993 Q1 1994 Q1 1995 Q1 1996 Q1 1997 Q1 1998 Q1 1999 Q1 2000 Q1 2001 Q1 2002 Q1 2003 Q1 2004 Financial Account Net Foreign Investment Net Portfolio Investment Net Other Investment Source: IMF International Financial Statistics Figure 10: Solow Growth Model y δ+n+g f(k) y*2 s(f(k))2 s(f(k))1 y*1 k*1 k*2 k y Figure 11: Endogenous Growth Model f(k) y1 s(f(k))2 s(f(k)1 y2 δ+n+g k2 k1 k