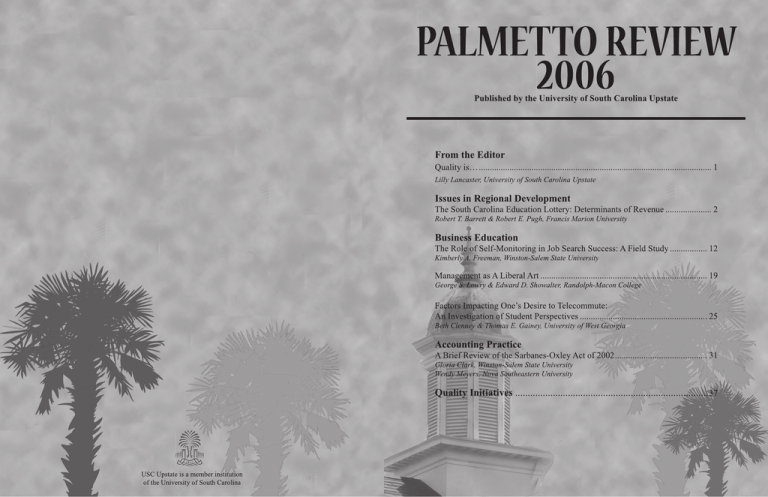

PALMETTO REVIEW

2006

Published by the University of South Carolina Upstate

From the Editor

Quality is… .......................................................................................................... 1

Lilly Lancaster, University of South Carolina Upstate

Issues in Regional Development

The South Carolina Education Lottery: Determinants of Revenue ..................... 2

Robert T. Barrett & Robert E. Pugh, Francis Marion University

Business Education

The Role of Self-Monitoring in Job Search Success: A Field Study ................. 12

Kimberly A. Freeman, Winston-Salem State University

Management as A Liberal Art ............................................................................ 19

George S. Lowry & Edward D. Showalter, Randolph-Macon College

Factors Impacting One’s Desire to Telecommute:

An Investigation of Student Perspectives .......................................................... 25

Beth Clenney & Thomas E. Gainey, University of West Georgia

Accounting Practice

A Brief Review of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 .......................................... 31

Gloria Clark, Winston-Salem State University

Wendy Meyers, Nova Southeastern University

Quality Initiatives ............................................................................. 37

USC Upstate is a member institution

of the University of South Carolina

PALMETTO REVIEW

Edited by

Lilly M. Lancaster, Ph.D.

William S. Moore Palmetto Professor in Quality Studies

School of Business Administration and Economics

University of South Carolina Upstate

Spartanburg, South Carolina

Volume 9

2006

PALMETTO REVIEW

Journal Audience and Readership

Palmetto Review is targeted toward both academicians and business professionals. The academic audience is interested in applied business-related research to use as a tool to enhance teaching and classroom

experiences for students. The professional/ practitioner audience is interested in sharing experiences about

a broad range of business-related topics. Topics for publication may be drawn from a variety of areas including manufacturing, service, government, health care and education. A section of the journal is devoted

to chronicling quality initiatives.

Journal Mission

Palmetto Review supports communication and applied research about business-related topics among

professionals and academicians in South Carolina and the Southeast.

Journal Content

Published annually by the University of South Carolina Upstate, the journal contains peer-reviewed

papers. All papers accepted are blind reviewed by at least two individuals. Letters to the editor and book

reviews may also be published.

Authors are discouraged from submitting manuscripts with highly statistical analyses and/or strong

theoretical orientation. Simple statistical analyses, tables, graphs and illustrations are encouraged. Please

see the “Guidelines for Authors” on the inside of the back cover of this journal.

Comments on published material and on how the journal can better serve its readers are solicited.

Contact:

Lilly M. Lancaster, Ph.D., Editor, Palmetto Review

William S. Moore Palmetto Professor in Quality Studies

School of Business Administration and Economics, University of South Carolina Upstate,

800 University Way, Spartanburg, S.C. 29303

Tel: 864/503-5597, Fax: 864/503-5583, E-mail: llancaster@uscupstate.edu

2006 REVIEW BOARD

School of Business Administration

and Economics

Jerome Bennett, Accounting

Richard Gregory, Finance

Faruk Tanyel, Marketing

Sarah P. Rook, Economics

Frank Rudisill, Management

University of Massachusetts

Joseph L. Balintfy, Professor Emeritus

PALMETTO REVIEW

Table of Contents

From the Editor

Quality is… ..........................................................................................................................1

Lilly Lancaster, University of South Carolina Upstate

Issues in Regional Development

The South Carolina Education Lottery: Determinants of Revenue .....................................2

Robert T. Barrett & Robert E. Pugh, Francis Marion University

Business Education

The Role of Self-Monitoring in Job Search Success: A Field Study .................................12

Kimberly A. Freeman, Winston-Salem State University

Management as A Liberal Art ............................................................................................19

George S. Lowry & Edward D. Showalter, Randolph-Macon College

Factors Impacting One’s Desire to Telecommute:

An Investigation of Student Perspectives ..........................................................................25

Beth Clenney & Thomas E. Gainey, University of West Georgia

Accounting Practice

A Brief Review of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 ..........................................................31

Gloria Clark, Winston-Salem State University

Wendy Meyers, Nova Southeastern University

Quality Initiatives ........................................................................................................37

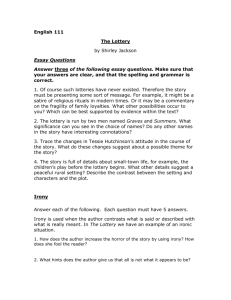

PALMETTO REVIEW

From the Editor

Quality is . . .

Variety. The ninth issue of Palmetto Review contains an impressive selection of articles on a variety of topics. As

I was reviewing the journal for publication, I became more and more interested, and absorbed in several of them.

First of all, the article about the South Carolina State Lottery by colleagues, Bob Barrett and Robert Pugh at Francis

Marion University, is most informative about the lottery, how it began and predictions for the future. Anyone who

lives in South Carolina is affected by the lottery. This article provides much insight into the process. Its currency

is validated by an article that appeared this last week in many State papers highlighting the impact that the North

Carolina State Lottery, as well as increasing gas prices, may have on South Carolina lottery ticket sales.

There are also three excellent articles related to business education. The discussion of self-monitoring behavior

and its impact on young graduates as they enter the job market is thought provoking. It gives us all an additional

dimension to consider as we work with our students preparing them for job interviews.

In the business education section, I particularly enjoyed the paper about management as a liberal art. This paper

discusses ways to bridge the gap between what we do in a business school and what are colleagues in the liberal

arts are doing. It is so important for us to work with colleagues campus wide. I look forward to sharing this paper

with my colleagues across campus.

Lastly, the article in the business education section about telecommuting had some results that were surprising

to me. I had assumed that individuals either wanted to telecommute or work in the office. From this preliminary

research, it appears that a more blended approach is desirable. Most of the respondents preferred to telecommute

approximately twenty hours per week if possible.

With a number of business schools currently in the process of recruiting accounting faculty, the article about the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 is also timely. As the article states, Sarbanes-Oxley is often called the ‘“CPA Employment

Act of 2002.”’ Many universities are feeling the pressure to enhance their accounting programs to satisfy student

demand while, at the same time, it appears that there are fewer and fewer qualified accounting faculty available on

the market. The next few years will prove interesting in accounting recruitment, partially due to the Sarbanes-Oxley

Act.

I hope that you will find the variety of topics in the 2006 issue of Palmetto Review of interest, also. Best wishes for

a successful 2006-2007 academic year!

Sincerely,

William S. Moore Palmetto Professor in Quality Studies

Volume 9, 2006

1

Palmetto Review

THE SOUTH CAROLINA EDUCATION LOTTERY:

DETERMINANTS OF REVENUE

Robert T. Barrett

Robert E. Pugh

Francis Marion University

ABSTRACT

The South Carolina Education Lottery, started in 2002, has been a big success for the state. Most of the

proceeds from the lottery, as was required by the legislation establishing the lottery, has gone to fund college scholarships. Technology and other educational needs have also been funded. This paper uses regression analysis to

examine the determinants of lottery revenues and related issues.

INTRODUCTION

ies continued, and by 2003, 39 states plus the District

of Columbia had established lotteries. This expansion

of state lotteries was greatly facilitated by advances in

information processing and communications technology,

which made lotteries more exciting for participants and

provided a high degree of control of lottery processing

to guard against corruption (Hills, 2005).

Six of the seven southeastern states established

lotteries during this period. In 1988, Virginia and Florida

started state lotteries, and, in 1993, Georgia started its

lottery. These three states held state-wide referendums

to gain the necessary approval for establishing their

lotteries. In 1998, Alabama held a state referendum on

establishing a lottery, but it failed. Two years later, in

2000, South Carolina voters gave approval for a state

lottery. More recently, in 2002, Tennessee held a referendum on a state lottery, and it was approved. In North

Carolina in 2005, legislation to establish a lottery was

passed.

As the South Carolina Education Lottery nears

the end of its third year, it is appropriate to analyze the

Lottery experience. In the first section of this paper,

some of the public concerns are reviewed. Secondly, a

brief look at the results from the first three years is presented. Then the study develops a statistical analysis of

the South Carolina lottery to identify the demographic

and economic factors that determine lottery revenues.

Lastly, this statistical analysis leads to an improved understanding of lottery revenue sources and serves as the

basis for examining policy issues related to the South

Carolina Education Lottery.

Lotteries are prominent throughout history.

The Great Wall of China was partly financed by a lottery. India, Greece, and Japan also had lotteries during

ancient times. Lotteries were used throughout the 1400s

and 1500s to finance various public works. In 1753 the

British Museum was funded by a lottery (Hills, 2005).

Lotteries have a mixed history in the United

States. In colonial times lotteries were used to finance

public works such as bridges, roads, and public buildings. The earliest of the colonial lotteries, authorized

by the English in 1612, helped fund the Jamestown,

Virginia, settlement. During the American Revolution,

lottery proceeds financed colonial troops. Lotteries lost

popularity in the period before the Civil War due to

corruption, such as fraud and rigged drawings. Many

states discontinued their lotteries. By 1860 only three

states—Missouri, Kentucky, and Delaware—continued

to maintain lotteries. Following the Civil War several

states again legalized lotteries, but again scandal and corruption undermined the public confidence. As a result,

by 1894 lotteries were prohibited in all states; and 35

states, including South Carolina, developed constitutional

provisions forbidding lottery operations (Hills, 2005).

During the early twentieth century Americans

gradually became more tolerant of gambling. Las

Vegas became the gambling capital of the country and

a number of states legalized race horse gambling. In

1964, New Hampshire began a new trend by legalizing

a state lottery. New York and New Jersey followed New

Hampshire’s lead by establishing state lotteries in 1967

and 1970, respectively. This expansion of state lotterVolume 9, 2006

2

Palmetto Review

The South Carolina Education Lottery: Determinants of Revenue

PUBLIC CONCERNS

REGARDING THE LOTTERY

play. Citizens with less than $50,000 income are three

times as likely to play as those with higher incomes.

There are many concerns about the lottery

including opposition to gambling, fiscal dependency

on lottery revenues, and regressive effects of lottery

participation. Here the concerns about the lottery are

discussed in terms of two areas: (1) the possible effects of

the lottery on other public policies and (2) the effects on

the poor and less educated segment of the population.

SOUTH CAROLINA LOTTERY PROCEEDS

DISTRIBUTION

THE FIRST THREE YEARS SCHOLARSHIPS AND OTHER RECIPIENTS

In March of 2002, the House and Senate passed

spending plans for the lottery proceeds that were vastly

different. Some labeled the House plan as one that ignored the poor (who would most likely be the ones who

would buy the most tickets) in favor of students who

could better afford college anyway (Sheinin, 2002).

One of the primary beneficiaries of the lottery

proceeds in the approved spending plan is the college

scholarship fund. There are four primary scholarships

available to graduates of South Carolina high school. The

Palmetto Fellow and LIFE scholarships were established

before the lottery was in existence. Lottery proceeds have

helped to expand these programs. The HOPE scholarship was initially funded with lottery proceeds, as was

the tuition assistance program for students attending

technical colleges (Edwards, 2002). Stated goals of these

scholarships include: “greater access to higher education;

bright, college-bound students choosing in-state schools,

rather than elite schools elsewhere; and bright college

graduates staying home, rather than adding to the brain

drain” (Brinson, 2002).

In addition to scholarships, lottery funds have

supported other public entities. Funds have been made

available to colleges and universities in the state for

technology upgrades. Endowed professorships have

been funded at the research universities. Lottery funds

have been used to purchase much needed school buses.

Local libraries have received funds along with the state’s

gambling addiction programs.

The plan approved by the Legislature also considered distribution of the revenues, which include ticket

sales, permit fees, retailer telephone fees ands other additional costs. Revenues are distributed as follows: 58

percent to prizes; 7 percent to retailer commissions; 6

percent to operating expenses; and 29 percent transferred

to the Education Lottery Account for disbursement.

Clearly the Education Lottery Account is for merit based

scholarships, with no regard for the family’s ability to

pay tuition. Some legislators and the State’s Commission on Higher Education have argued that more of the

dollars should go for needs based programs (Strensland,

2002).

For the fiscal year ending June 30, 2004, lottery

revenues totaled $950 million. After payouts and other

Effects on Public Policy

Purchasing lottery tickets is sometimes perceived

as the poor person’s version of gambling. A 1996 article

by Joseph P. Shapiro (Shapiro 1996), speaking mainly

of gambling in casinos, asks a number of pertinent questions: Is there economic benefit to gambling? Does

gambling create economic development? What are the

social costs? Does gambling lead to crime?

Another general concern with gambling is that

up to 30 percent of youth participate in gambling in some

form (Crary, 2003). Still, another concern is presented in

the Wall Street Journal (Wall Street Journal, 2004). The

Journal editorial chastises legislatures who use money

irresponsibly when they count on lottery/gambling proceeds to fund ongoing programs. Some actually see these

revenues as means to expand programs.

With interstate and international business becoming more and more electronic, gambling is following suit.

The 1961 Federal Wire Act made betting on sports on

the telephone or on the Internet illegal in the U.S. This

form of gambling, however, is not illegal in many other

countries and gambling has become big business overseas. An estimated $5.7 billion in revenues was earned

world-wide from online gambling in 2003. The majority

of the gamblers demographically were American (Angwin, 2004).

Effects on the Poor and Less Educated

Opponents of the South Carolina lottery voiced

their opposition early on stating that these types of revenue generators for state programs create exploitation of

the poor. A December 24, 2002, editorial in The State

(Editorial, The State, 2002) referenced a study conducted

by the lottery commission that indicated that lottery players are “disproportionately poor and black and not highly

educated.” Blacks play at a rate 50 percent higher than

whites. Households with incomes less than $40,000 play

more than households with higher incomes (proportionately). Fewer college graduates play when compared

with those with no college education. The numbers are

even more pronounced when looking at the intensity of

Volume 9, 2006

3

Palmetto Review

Robert T. Barrett, Robert E. Pugh

expenses, about $270 million was used to fund college

scholarships. Officials had originally estimated about

$250 million for the year. Much of the increase was

attributed to excitement, and subsequent heavy ticket

sales, surrounding the large Powerball jackpots (AP

Report, 2004). From the first sales in January 2002

through October 14, 2005, over $664 million has been

transferred from the lottery revenues to the Education

Lottery Account (AP Report, 2004, www.sceducationlottery.com).

This reflects the fact, observed by others, that higher income people spend a smaller proportion of their income

on the lottery than lower income people.

The third explanatory variable in the model is

accommodation tax. This tax is on motel/hotel rooms

and is a measure of the flow of people overnighting in a

county, including both tourist and business travelers. In

2002 South Carolina collected nearly $33.5 million in

accommodation taxes, but the tax collections are very

unevenly distributed among the state’s 46 counties with

two counties collecting almost no taxes and one county,

Horry, collecting $12.2 million or almost one-third of

the State’s total. Referring to the regression model for

year 2002, the accommodation tax variable, AT02, has

a coefficient of +.00121 indicating that, on average, for

a county a $1000 increase in accommodation tax collections would be associated with an increase of $.00121

million or $1,210 in lottery sales. Table 1 provides

accommodations tax collections and associated lottery

sales for 2002 for the top five counties in accommodation tax collections. These five counties account for

approximately 95.5 percent of South Carolina 2002 accommodation tax collections.

The remaining two variables in the model are

NCAP, North Carolina accessible population, and GAB,

Georgia counties that border on South Carolina (0-1

variable). These variables are described fully in the

Model-Based Analysis section, evaluating the effects

of counties in North Carolina and Georgia on South

Carolina’s lottery revenues.

A STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF

THE SOUTH CAROLINA

EDUCATION LOTTERY

To develop an understanding of the factors

related to lottery sales or revenue, statistical models are

developed of lottery revenue as a function of economic,

demographic, and geographic variables. Five models are

developed, one for each calendar quarter of 2002 and one

for the year 2002. The complete statistical description

of the five models developed is found in the Appendix.

All the models are strong statistically with the R-square

values ranging from .96 to .91 indicating that statistically

each model explains more than 90 percent of the variation

in the dependent variable, lottery revenue.

An Example of Findings Particular to South Carolina

Examining the model for the year 2002, the

population variable, POP, and per capita income variable, PCI are the first two explanatory variables involved.

Note that the population variable, POP, is an explanatory

variable both acting alone and acting in combination

with per capita income, PCI. This part of the regression

model has the form:

TABLE 1

Estimated Impact of Visitors on Lottery Sales Based

on Accommodation Tax Collections for the

Top Five Counties in Accommodation Tax

.200POP - .00314POPxPCI.

County

The POPxPCI variable, the product of population and

per capita income, represents the purchasing power of

the resident population of the county. One implication

is that for a county with a specified population, lottery

sales decrease as the per capita income of the county

increases.

The hypothetical examples below illustrate the

contribution to lottery revenue for two counties with

80,000 residents but with different levels for PCI:

Population

80,000

80,000

Volume 9, 2006

PCI

$15,000

$20,000

Horry

Charleston

Beaufort

Richland

Greenville

Accommodation Tax

Collections in 2002

(million$)

Lottery Sales in 2002

Associated with

Accommodation Tax

Collections ($)

12.22

6.72

4.28

1.62

1.60

14,786

8,131

5,179

1,960

1,936

MODEL-BASED ANALYSES

Border Effects

The state of Georgia has had a lottery for a number of years. Has the introduction of the South Carolina

Education Lottery had any impact in lottery sales for the

Georgia counties that border South Carolina? Lottery

Contribution to Lottery Sales

$12.232 million

$10.976 million

4

Palmetto Review

The South Carolina Education Lottery: Determinants of Revenue

summarized in Table 3. In the second column of Table

3 the proportion of each North Carolina county that is

directly across the border from the corresponding South

Carolina county is shown in parentheses. For example,

for Cherokee County, 100 percent of Cleveland County

and 60 percent of Rutherford County are directly across

from Cherokee County. Therefore the NCAP variable

for Cherokee County includes all of Cleveland County’s

population plus 60 percent of Rutherford County’s population.

One question of particular interest is: When

North Carolina implements its lottery, in 2006, will this

reduce the South Carolina lottery sales? Our modelbased estimates for 2002 are that South Carolina lottery

sales to North Carolina residents were $43.28 million;

and since the total 2002 sales were $626.9 million, sales

to North Carolinians were 6.9 percent of the total. In

fiscal year 2004, South Carolina lottery sales were $950

million. If the same 6.9 percent held, this means that

for 2004 sales to North Carolina residents were about

$65.5million. With the advent of North Carolina’s lottery South Carolina might lose a significant part of these

sales. In addition, South Carolina residents will purchase

lottery products in North Carolina to some extent. A

rough estimate of South Carolina’s annual sales loss is

$80-$90 million in 2004 prices. This is significantly

lower than the $150 million a year loss in South Carolina

sales predicted by a number of South Carolina lottery

officials. South Carolina, of course, may be able to

mitigate its loss in sales in the early years of the North

Carolina lottery because of South Carolina’s ability to

rollout fresh games and by offering the very profitable

and popular Powerball drawings (Strensland, 2002).

However, in the longer term the two state lotteries will

probably be roughly equal in attractiveness to purchasers. At that point, North Carolina may have a slight

advantage mainly because of the large South Carolina

population that resides and works in the Charlotte, NC,

metropolitan area. Thus, the long term rough estimate

of South Carolina’s annual net revenue loss of $80-$90

million, in 2004 prices, reflects North Carolina capturing the estimated $65.5 million that South Carolina was

selling to North Carolina residents plus sales to South

Carolinians residing in the Charlotte metropolitan area.

The remaining variable in the year 2002 model

is the Georgia boundary (GAB) variable. This is a binary variable with a “1” for each South Carolina county

that borders on Georgia and a “0” for all other counties.

In the model this variable has a coefficient of –2.613,

indicating that for counties bordering Georgia there is

an associated reduction in lottery revenue. This loss is

expected because of the competition in these counties

sales for all counties of Georgia over the period from

2000 through 2003 show an overall increase. Lottery

sales declined from 2000 to 2001. Georgia experienced

about a 12 percent increase in 2002 compared with 2001

sales. Lottery sales in 2003 were about 6.3 percent more

than in 2002 statewide.

Table 2 shows the percentage changes in lottery

sales from year to year for the Georgia counties bordering South Carolina, all other Georgia counties, and the

total State. While the State experienced a healthy 6.31

percent increase in lottery sales from 2002 to 2003, the

counties on the South Carolina border showed an almost

2 percent decrease in sales. Over this 2002-2003 period,

six of the 13 border counties experienced declines in

sales, two were virtually flat, two others experienced

less than 3 percent increases, and one other a 5.3 percent

increase. This clearly indicates that South Carolina’s

lottery has dampened Georgia’s lottery sales in those

counties bordering South Carolina.

TABLE 2

Increases (Decreases) in Lottery Sales for the

13 Georgia Counties That Border South Carolina, the Other

Georgia Counties, and All Counties in Georgia

From

To

Border Counties

(%)

2000

2001

2002

2001

2002

2003

(3.87)

6.78

(1.87)

Other

Counties

(%)

Total Sales

(%)

(5.55)

12.76

7.38

(5.35)

12.03

6.31

The variable measuring the North Carolina assessable population, NCAP, for South Carolina counties

that border North Carolina has a coefficient of +.0250

in the model for the year 2002, indicating a positive

contribution of the North Carolina counties to South

Carolina lottery sales. The NCAP variable measures

the market in North Carolina for cross-border sales.

For example, Roberson County, North Carolina, with

a population of 123,300, is directly across the state line

from Dillon, South Carolina. The Dillon County NCAP

is 123.3. Therefore the lottery sales in Dillon County

associated with this particular North Carolina population is (.0250)(123.3) = $3.08 million per year. In like

manner, the 11 South Carolina counties bordering North

Carolina have increased lottery sales due to cross-border

sales. Based on the regression model York County has

the largest cross-border sales; since its NCAP = 885.9,

the model estimates York County’s annual sales to the

North Carolina market at (.0250)(885.9) or $22.15 million. Estimated impacts of the North Carolina Accessible

Population on the South Carolina border counties are

Volume 9, 2006

5

Palmetto Review

Robert T. Barrett, Robert E. Pugh

from the more well-established Georgia lottery. From the

model, on average each of the 11 South Carolina counties

bordering Georgia is associated with lost sales of $2.613

million per year. Thus, without the cross-border sales to

Georgia in its initial year, the sales of the South Carolina

lottery would have been an additional $28.743 million

or 4.6 percent higher.

TABLE 4

Sales for 2002 in Millions of Dollars.

TABLE 3

SC

Counties

Cherokee

Chesterfield

Dillon

Greenville

Horry

Lancaster

Marlboro

Oconee

Pickens

Spartanburg

York

Total

Bordering NC

Counties

Cleveland (1.00)

Rutherford (0.60)

Arson (1.00)

Union (0.27)

Roberson(1.00)

Polk (0.15)

Henderson (1.00)

Transylvania (0.40)

Brunswick (1.00)

Columbus (1.00)

Union (0.73)

Scotland (1.00)

Richmond (1.00)

Transylvania (0.30)

Jackson (1.00)

Transylvania (0.30)

Rutherford (0.40)

Polk (0.85)

Mecklenburg (1.00)

Gaston (1.00)

Estimated

Effect on

Lottery

Sales

($1,000,000)

134.0

3.35

58.7

1.47

123.3

103.6

3.08

2.59

127.8

3.20

123.7

82.6

3.09

2.06

42.0

1.05

8.9

40.8

0.22

1.02

885.9

22.15

Quarter

3

Quarter

4

Total

Sales

$185

$134

$115

$192

$626

Quarterly

index

1.18

0.86

0.73

1.23

Determinants of Lottery Sales

The regression models presented in the Appendix provide additional insight into the relative strength

of the statistical determinants of South Carolina lottery

sales. Table 5 summarizes the relative strength of the

determinants under four general factors: Residents, Visitors, Border Effects, and Other. “Residents” represent

sales to each county’s resident population, and hence

relates directly to the model variables population (POP),

per capita income (PCI), and the product of these two

variables, with this product representing the personal

income of a county. “Visitors” represent lottery sales to

those visiting the county on either business or pleasure.

This factor is measured in our model by the accommodations tax (AT) variable. “Border Effects” represent the

influence of the North Carolina and Georgia counties

bordering South Carolina. This factor is measured by

the North Carolina accessible population (NCAP) and

Georgia border counties (GAB) variables. “Others”

represent primarily the lottery sales unexplained by the

model plus the model constant term. For example, in the

model for the first quarter of 2002, the R-square value

is .96 indicating that .04, or four percent, of the lottery

sales for that quarter are not explained by the model.

This unexplained sales along with the constant term of

.276 constitute the “Others” factor shown in Table 5.

Table 5 was developed by applying each model

to the 46 counties of South Carolina and summarizing the

results. For example, for the year 2002, or first row of the

table, the year 2002 model is applied to each county and

the results for each term of the model are retained separately. Then the results for the 46 counties are added for

the POP, population, and POPxPCI, product of population and per capita income, terms to obtain the Residents’

contribution to sales. In like manner, the contribution to

sales for Visitors and Border Effects are each computed.

The “Others” contribution is the remainder of the sales

not accounted for by the other three determinants. To

illustrate, in 2002 total lottery sales were $626 million,

and from the model application as just described, $498

43.28

Seasonal Pattern of Sales

The models for the four quarters of 2002 presented in the Appendix have a structure similar to the

model for the year 2002. The quarterly distribution of

lottery sales in 2002, the first year of operation, shows a

definite seasonal pattern. For that year lottery sales for

the first and fourth quarters were high and sales for the

other two quarters were relatively low. Table 4 shows

quarterly sales levels for 2002 along with the quarterly

index values. This pattern is shown clearly by the quarterly seasonal indices for lottery sales in 2002. South

Carolina lottery officials have indicated that this seasonal

pattern of sales is expected to be typical for other years,

with lighter sales in the warmer, vacation-period of the

year (Davenport, 2002).

Volume 9, 2006

Quarter

2

(millions)

Estimated Impact of North Carolina Accessible Population

on the South Carolina Border Counties

NC

Accessible

Population

(1000)

Quarter

1

Year

6

Palmetto Review

The South Carolina Education Lottery: Determinants of Revenue

TABLE 5

Proportion of South Carolina Lottery Sales Explained By Specified Determinants in 2002 and Quarters of Year 2002

Statistical Determinants

Residents:

Time Period

Year 2002

Quarter 1

Quarter 2

Quarter 3

Quarter 4

Visitors:

Unexplained

Population and

Per Capital Income

Border Effects:

Accommodations Tax

0.80

0.85

0.81

0.77

0.74

0.07

0.06

0.08

0.07

0.09

million were associated with Residents, $41 million with

Visitors, $14 million with Border Effects, and $73 million

with “Others.” The proportions are then computed for

these four types of contributions in the first line of Table

5. The proportions are computed for each quarter of 2002

utilizing the respective models for the four quarters.

As Table 5 shows, lottery sales associated with

Residents account for a large portion of sales, 80 percent for year 2002 and between 74 and 85 percent for

the quarters of that year. Thus, eight out of every ten

dollars of lottery sales are associated with the resident

population, their number and income level. Visitors are

associated with seven percent of lottery sales for 2002,

with the quarterly level varying from six to nine percent.

The Border Effects include two forces. First, on the

North Carolina border there are sales associated with

the over-the-border North Carolina population. Second,

on the South Carolina-Georgia border there are sales to

Georgia residents by South Carolina and sales to South

Carolina residents by Georgia, since each state has its

own lottery. Note in the table that for the year 2002,

two percent of lottery sales are associated with Border

Effects. However, in the second and third quarters the

South Carolina Lottery experienced a loss in sales, two

percent in the second quarter and one percent in the third.

This means that in those quarters purchases by South

Carolina residents from the Georgia lottery exceeded the

sales to North Carolina residents from the South Carolina

lottery.

Lottery Sales

0.02

0.03

-0.02

-0.01

0.07

0.11

0.05

0.13

0.17

0.01

typically academically more advanced) families.

This argument can be addressed in an approximate way by using the regression model for 2002

presented in Table A1. As mentioned in a previous

discussion, the residents’ lottery spending, called RLOS

here, is described statistically by the population (POP)

and per capita income (PCI) variables as structured in

the first two terms of the model. That is:

RLOS = .200POP - .00314POPxPCI.

Let’s assume that we have a hypothetical county with

a population equal to the median population of South

Carolina’s 46 counties, 52,500 (POP = 52.5). For this

hypothetical county we can compare lottery spending

by residents for a lower income county, say with a per

capita income of $20,000 (PCI = 20), with the spending

of a higher income county, say with a per capita income

of $30,000 (PCI = 30). Using the population of 52,500

we have:

RLOS = .200(52.5) - .00314(52.5)PCI or

RLOS = 10.5 - .165PCI.

Then for a per capita income of $20,000:

RLOS = 10.5 - .165(20) = 7.2,

And for a per capita income of $30,000:

Regressive Impact of Lottery

A general policy concern with state lotteries is

that the lower income groups spend a larger proportion

of their income on the lottery than higher income groups.

South Carolina residents exhibit this typical behavior in

their lottery spending. This in effect means that lottery

spending acts as a regressive state tax. This bolsters the

argument that lower income residents are paying for tuition scholarships for students from higher income (and

Volume 9, 2006

NC Accessible

Population and

GA Border

Others:

RLOS = 10.5 - .165(30) = 5.0.

From this it is seen that the $20,000 per capita income

group spending is about $137 ($7,200,000/52.5 = $137)

per person, whereas for the $30,000 per capita income

group the per capita lottery spending is about $95

($5,000,000/52.5 = $95). This means that the $20,000

per capita income group spends about .07 percent

($137/$20,000 = .007 or .07 percent) of their income

7

Palmetto Review

Robert T. Barrett, Robert E. Pugh

on the lottery compared with .03 percent ($95/$30,000

= .003 or .03 percent) for the $30,000 per capita income

group. This is put in perspective by noting that the per

capita lottery spending by residents in the entire State

in 2002 was about $125, this from the lottery spending

by residents in 2002 of $498 million, discussed previously, divided by the South Carolina population of four

million.

It should be understood that these lottery spending estimates for per capita income groups are rough estimates. This is because the models of the determinants of

lottery spending use the average per capita income levels,

whereas our interpretations are made for subpopulations

that have specified per capita income levels. While these

interpretations may result in estimates with some bias,

the results are seen as reasonable as to direction, in that

lower income groups spend a larger proportion of their

incomes on the lottery, and reasonable as to magnitude

compared to the $125 per capita lottery spending, which

is determined independently of the regression model.

findings are:

• In its initial year of operation, the sales of South

Carolina’s lottery were distributed in the following way: Residents—90 percent, Visitors—seven

percent, Cross-border—two percent. This leaves

1 percent of the sales unexplained by the statistical model.

• Lottery sales are regressive relative to income.

Those with lower incomes spend a larger proportion of their income on the lottery. For example,

it is estimated that with a $20,000 annual income,

seven percent of the income is spent on the lottery

whereas those with $30,000 in income spend only

three percent.

• In its first year, the South Carolina lottery had

significant cross-border sales with North Carolina

and with Georgia. North Carolina did not have

a lottery in the initial year of the South Carolina

lottery, and cross-border sales to North Carolina

residents were $43.28 million or 6.9 percent of

total sales. Georgia, with its well-established

lottery, drew $28.73 million in net sales from

South Carolina, reducing South Carolina’s sales

by 4.6 percent.

• South Carolina Lottery sales were seasonal in

its initial year with a quarterly index pattern of

1.18, 0.86, 0.73, and 1.23, respectively. This is a

typical pattern for lottery sales, light in the springsummer and heavy in the fall-winter period.

While these findings are based in the initial year of lottery

operations, it is reasonable to assume that similar patterns

of results hold for subsequent years of the lottery.

Although it appears that the South Carolina Educational Lottery has operated without either corruption

or malfeasance since 2002, a number of proposals for

change have been made. These changes relate primarily

to two areas: (1) the administration of lottery operations

and (2) the allocation of the lottery generated funds

among educational programs. In lottery operations, The

South Carolina Legislative Audit Council recommended

that cost cutting should be made, such as reducing the

number of cellular phones used and re-evaluating the use

of vehicles. Another administrative change suggested is

cutting the seven percent fee paid retailers on lottery sales

to six percent (www.scgovernor.com

www.scgovernor.com 2003). Governor

Mark Sanford made this recommendation several times,

including the Fiscal Year 2006-07 Executive Budget in

which this saving was estimated at $8.4 million (Sanford

2006).

In the area of allocation of educational support

funds from the lottery, two proposals of interest have been

made. First, it has been proposed that lottery sales be

CONCLUSION

Since the first ticket was sold in January 2002,

the SC Education Lottery has been successful, exceeding

expectations of the most optimistic supporters. By the

end of the third complete fiscal year, ticket sales totaled

just under $3 billion (fiscal year ending June 30, 2005).

Ticket sales in the first three fiscal years were $724.3

million (2003), $950.0 million (2004), and $956.0 million (2005) (www.sceducationlottery.com).

As stated in current SC Education Lottery legislation, “proceeds of lottery games must be used to support

improvements and enhancements for educational purposes and programs as provided by the General Assembly

and that the net proceeds must be used to supplement,

not supplant, existing resources for educational purposes

and programs” (www.sceducationlottery.com). By the

end of the 2005 calendar year, including distributions

made in 2002 (a partial fiscal year), funds distributed to

the SC Education Lottery Account exceeded $1 billion.

Over 460,000 scholarships for students attending colleges

and universities and technical colleges were funded by

the lottery account. Over $330 million was provided to

K-12 public schools, in addition to 400 buses, and $28

million for textbooks (www.sceducationlottery.com).

In this study the focus is on understanding the

economic and demographic consequences of lottery sales

by the South Carolina Education Lottery. The methodology employed is regression modeling that represents

lottery sales in South Carolina’s 46 counties as a function

of economic and demographic variables. The principal

Volume 9, 2006

8

Palmetto Review

The South Carolina Education Lottery: Determinants of Revenue

subject to the state income tax (Calhoun, 2003). The Lottery Commission has opposed this idea, but this idea may

well be raised again (Sheinin, 2002). A second example

of changes in the allocation of educational support funds

is to direct more funds to K-12 or early childhood education rather than to college scholarships. The interest in

this change was sparked by the recent court decision in

the “minimally adequate” school funding lawsuit verdict

(www.sceducationlottery.com 2006).

12. Eichel, Henry, (2002) “Stores near the Borders

Lead Lottery Sales,” The State, Columbia, S.C, March

17, 2002, B 1.

13. “Five Key Issues in 2006,” (2006) The State, Columbia, S.C., January 8, 2006, D1.

REFERENCES

14. “Greenville News Editorializes in Support of Gov.

Sanford’s Lottery Retailer Cut,” (2003) State of South

Carolina, Office of the Governor, www.scgovernor.com,

December 5, 2003.

1. Angwin, Julia, (2004) “Could U.S. Bid to Curb

Gambling on the Web Go Way of Prohibition?” The Wall

Street Journal, August 2, 2004, B1.

15. Hills, Chad, (2005) “A History of the Lottery,”

Focus on Social Issues, www.family.prg/cforum/foci/

gambling/lottery/10026528.cfm. December 27, 2005.

2. AP Report, (2004) “S.C. Lottery Brings in Almost

$1 Billion,” Morning News, Florence, SC, August 9,

2004, A 7.

16. Monk, John, (2000) “Hodges put Machine to Work

for Lottery,” The State, Columbia, S.C., November 9,

2000, B1-B2.

3. Barrett, Robert T., and Pugh, Robert E., (2003)

“Success of the South Carolina Education Lottery – Six

Month Report,” Southeast Decision Sciences Institute

Proceedings, February 2003, pp. 313-315.

17. News Article, (2004) “More than Half a Billion

Transferred to Education,” www.sceducationlottery.com.

May 13, 2004.

18. Sanford, Mark, Governor of South Carolina, (2006)

Executive Budget, State of South Carolina, www.scgovernor.com, January 4, 2006.

4. Brinson, Claudia Smith, (2002) “Merit-based Scholarships are Misguided, Largely Ineffective,” The State,

Columbia, S.C, July 28, 2002, D 1, 5.

19. Scoppe, Cindi Ross, (2004) “Lottery Opponents

Would Love to See Rules Spelled Out Before Vote,” The

State, Columbia, S.C., May 4, 2000, A14.

5. Calhoun, Cecil, (2003) “Budget Debate Leaves Public Ed Funding,” www.thescea.org, March 14, 2003.

20. Shapiro, Joseph P., (1996) “America’s Gambling

Fever: The nation’s favorite pastime comes under fire

from those who fear it won’t help communities and

families in the long run,” U.S. News & World Report,

January 15, 1996, pp. 52-60.

6. Crary, David, (2003) “Experts Say Gambling Problems on the Rise among American Youth,” Morning News

(Florence, SC), July 14, 2003, A1, 5.

7. Davenport, Jim, (2002) “Lottery Revenue Slower

than Expected in July,” Morning News, Florence, S.C.,

August 30, 2002, A5.

21. Sheinin, Aaron, (2002) “Bill Clears House, is

Branded Elitist,” The State, Columbia, SC, March 15,

2002, A 1, 9.

8. Edgar, Amy Geier, (2004) “S.C. lottery, USC form

Unique Partnership,” Morning News, Florence, SC,

August 9, 2004, A 7.

Editorial, (2002) The State, December 24, 2002, A8.

22. Sheinin, Aaron Gould, (2003) “Proposed Lottery

Sales Tax Opposed,” The State, Columbia, SC, December

3, 2003, B 1.

10. Editorial, (2004) “Political Gambling,” Wall Street

Journal, July 19, 2004, A 10.

23. Strensland, Jeff, (2002) “Lottery Fuels Scholarship

Debate,” The State (Columbia, S.C), July 28, 2002, D 1, 6.

11. Edwards, Laura, (2002) “Gambling on their Future,”

Morning News, Florence, S.C., June 6, 2002, A1, 8.

24. Strensland, Jeff, (2005) “S.C. Games has Means to

Compete with N.C.” The State, Columbia, SC, www.

thestate.com, May 9, 2005.

9.

Volume 9, 2006

9

Palmetto Review

Robert T. Barrett, Robert E. Pugh

25. “Who Went to the Polls in South Carolina,” (2000)

The State, Columbia, S.C., November 8, 2000, A16.

26. www.sceducationlottery.com.

APPENDIX

REGRESSION MODELS EXPLAINING

LOTTERY SALES

The model statistics provided in the lower

rows of Table A1 provide overall measures of the statistical reliability of the models. The F-ratios provide

a statistical test of the significance of the overall model

relationship between the dependent variable and the set

of independent variables. For all five of these models

the F-ratios indicate the overall model relationship is

strong, significant at the 99 percent confidence level or

higher. Thus, each model represents a relationship that

is highly significant statistically. The R-square values

represent another overall measure of model statistical

strength, measuring the proportion of the variation in

the dependent variable that is explained by the set of

independent variables in the model. In these models the

R-square values range from .96 to .91 indicating that each

model statistically explains more than 90 percent of the

variation in the dependent variable, lottery revenue.

Another important measure of model reliability

is the t-scores that measure the statistical reliability of the

individual independent or explanatory variables included

in the model. The coefficients of the explanatory variables

in the regression model for year 2002, for example, are

significant at the 97 percent level or higher. The t-scores

are given in parentheses below each model coefficient.

Note that the same independent variables are included

in each of the five models to provide easy comparison in

the interpretation of the models. This causes three of the

coefficients of explanatory variables, two in the model

for the third quarter and one in the model for the fourth

quarter to be of lower level of significance than .97.

An interesting aspect of the structure of these

models is that the population variable, POP, appears in

the models both acting alone and acting in combination

with per capita income, PCI. The combination variable,

POPxPCI, is called an interaction variable or crossproduct variable, and in this situation the cross-product

variable substantively represents the spending power of a

county’s population. Such variables are often important

in representing a nonlinear relationship among variables,

and in these models there is a nonlinear relationship

between the POP and PCI variables acting together and

the dependent variable, lottery revenue. In this study the

interaction variable provides the basis for an increased

understanding between per capita income and lottery

spending.

The methodology employed in this study

involved the development of regression models that

represented lottery revenues from sales as a function of

economic, demographic, and geographic variables. The

observations on the variables used to estimate the models

were taken from the 46 counties of South Carolina. Five

models are developed, one for each calendar quarter of

2002 and one for the year 2002. The interpretation of

these models was a primary basis in the study for providing an improved understanding of the factors related to

lottery sales revenues. The model for the year 2002 is:

LR02 = 1.61 + .20 POP – 0.00314 POPxPCI +0.00121

AT02 + 0.025 NCAP – 2.61 GAB

where:

LR02-Lottery sales revenue for each county in

2002 in millions of dollars

POP-Population of county in 2000 in thousands

PCI- Per capita income of county in 2000 in

thousands of dollars

AT02-Accommodation taxes collected in county

in 2002 in thousands of dollars

NCAP-North Carolina population accessible to

South Carolina counties

on the South Carolina-North Carolina border in

2000 in thousands

GAB-South Carolina counties that border on

Georgia (0-1 variable)

The complete statistical description of the five

models developed is provided in Table A1. These five

models all include the same dependent and independent

variables, except that the dependent variable and one of

the independent variables are represented on a quarterly

basis in the four quarterly models. Lottery revenue, the

dependent variable, is represented for each quarter of

2002 as LRQ1, LRQ2, LRQ3, and LRQ4, respectively.

Likewise, the independent accommodations tax variables

are represented by quarter as ATQ1, ATQ2, ATQ3, and

ATQ4, respectively.

Volume 9, 2006

10

Palmetto Review

The South Carolina Education Lottery: Determinants of Revenue

TABLE A1

Regression Models Representing Lottery Sales Revenue as a Function of County Characteristics

VARIABLE/

STATISTIC

Dependent Variable:

Lottery Revenue

($1,000,000)

Constant Term

QUARTER

1 MODEL

QUARTER QUARTER 3 QUARTER

2 MODEL

MODEL

4 MODEL

YEAR

2002

MODEL

LRQ1

LRQ2

LRQ3

LRQ4

LR02

0.276

0.355

0.451

0.404

1.61

POP

.0654

(6.15)

POP

.0453

(4.96)

POP

.0330

(3.56)

POP

.0643

(4.41)

POP

.200

(5.09)

POPxPCI

-.00109

(2.89)

POPxPCI

-.00758

(2.38)

POPxPCI

-.000458

(1.43)

POPxPCI

-.00118

(2.33)

POPxPCI

-.00314

(2.30)

Accommodation

Tax ($1000)

ATQ1

.00286

(3.25)

ATQ2

.00108

(4.69)

ATQ3

.000551

(5.21)

ATQ4

.00273

(4.87)

AT02

.00121

(5.02)

North Carolina Accessible

Population (1000)

NCAP

.00873

(9.58)

NCAP

.00343

(4.36)

NCAP

.00250

(5.21)

NCAP

.0104

(8.26)

NCAP

.0250

(7.38)

Georgia Boundary (0 or 1)

GAB

-.810

(2.77)

GAB

-.567

(2.24)

GAB

-.482

(1.89)

GAB

-.450

(1.12)

GAB

-2.61

(2.40)

0.96

220.4

0.94

133.3

0.91

90.9

0.93

115.3

0.95

165

Independent Variables:

Population (1000)

Population (1000) x

Per Capita income ($1000)

Model Statistics:

R-Square

F-Ratio

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Robert T. Barrett is Professor of Management

and Associate Dean in the School of Business at Francis

Marion University. Dr. Barrett teaches and researches

in management science, statistics, and operations management. His latest research has focused on supply

chain management and regional economic development

including projects studying the influences of highways,

influences of communicable diseases, and influences

of the state-run lottery on the regional economy. He

has published scholarly papers in journals including the

Southern Business Review, the International Journal of

Computers and Operations Research, the Production

and Inventory Management Journal, Simulation, and

the Journal of Travel and Tourism Management. He is

a regular contributor as reviewer for Decision Sciences

and the International Journal of Computers and Opera-

Volume 9, 2006

tions Research and a regular participant in regional and

national professional meetings.

Robert E. Pugh is Professor of Management

and the Eugene A. Fallon, Jr. Professor of Production

Management in the School of Business at Francis Marion University. Dr. Pugh teaches and researches in management science, operations management, and statistical

model building. His recent research focuses on the effects of existing and proposed highways, tourism, and retirement migration on regional economic development.

He has published scholarly papers in Coastal Business

Review, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management,

Mathematical Programming, Southern Business Review,

and other journals. He participates in professional meetings as a reviewer, discussant and presenter.

11

Palmetto Review

THE ROLE OF SELF-MONITORING

IN JOB SEARCH SUCCESS: A FIELD STUDY

Kimberly A. Freeman

Winston-Salem State University

ABSTRACT

Students nearing graduation are often quite concerned with securing job offers that will launch their careers. This study investigates whether getting second interviews, receiving job offers, and accepting a job prior to

graduation from an MBA program is more likely for those individuals who are high on self-monitoring compared

to those who are low on self-monitoring. The results of hierarchical regression analyses support these hypotheses

by demonstrating that the prospects on these outcomes are positive for students who report to be high (rather than

low) on self-monitoring behavior. Implications of these results are discussed, as are directions for future research.

INTRODUCTION

Unckless, & Hiller, 2002; Gangestad & Snyder, 2000;

Turnley & Bolino, 2001).

A recent study of employed Executive MBA

students revealed a relationship between self-monitoring and the Big Five personality traits. Barrick, Parks,

& Mount (2005) found that when self-monitoring was

high, the relationships between three of the Big Five

personality traits (Extroversion, Emotional Stability, and

Openness to Experience) and supervisory ratings of interpersonal performance were attenuated. The interpersonal

performance factor included interpersonal skills, rapport

in relationships, cooperation, communication, listening,

and other aspects. Self-monitoring did not, however,

moderate the relationships between supervisory or peer

ratings of task performance and personality traits (Barrick, et al, 2005).

Another study found that people who were more

demographically different (e.g., citizenship, race, etc.)

from their coworkers created more negative impressions

than did more similar coworkers, but “these impressions

were more positive “when they were either high SMs or

more extroverted (Flynn, Chatman, & Spatero, 2001).

In a cross-cultural study of college students, Goodwin

& Pang Yew Soon (1994) found the British subjects

were higher SMs than their Chinese counterparts which

supported their hypothesis that Western students would

be significantly higher SMs than those from Eastern

cultures, as hade been found by Gudykunst, Yang &

Nishida (1987). Zweigenhaft & Cody (1993) reported

that black students scored significantly lower on Snyder’s

self-monitoring scale than their white colleagues on a

predominantly white college campus.

Job search success may depend upon a number of

factors. Organizations typically gather basic information

about the job applicants through the application process

and resume in order to decide whom will receive an initial

interview. Candidates who are successful in the first interview are often required to engage in a second interview

prior to the hiring decision. The interview is generally

regarded as a useful way to discern whether or not the

candidate is a good fit or “match” for the organization.

Considerable research on interview techniques and dynamics has been conducted. However, few researchers

have studied the effect of a personality trait identified as

self-monitoring behavior on hiring decisions.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Self-monitoring has been studied extensively

across a wide variety of social interaction circumstances. In their comprehensive review of published

literature, Gangestad & Snyder (2000) summarize that

“high self-monitors may be highly responsive to social

and interpersonal cues of situationally appropriate

performances,” whereas “for those low self-monitors,

expressive behaviors are not controlled by deliberate attempts to appear situationally appropriate; instead, their

expressive behavior functionally reflects their own inner

attitudes, emotions, and dispositions.” In other words,

high self-monitors (SMs) are willing and able to display

behaviors to impress other people in contrast to low

SMs who resist or are unable to do so (Day, Schleicher,

Volume 9, 2006

12

Palmetto Review

The Role of Self-Monitoring in Job Search Success: A Field Study

Leadership and self-monitoring behavior research has revealed several relationships of self-monitoring with leadership emergence and leader flexibility.

Compared with low SMs, high SMs initiated structure

more often and emerged as leaders more often indirectly

through initiating structure (Dobbins, Long, Dedrick, &

Clemons., 1990). In another study, high SM was associated with leadership capabilities of social perceptiveness

and behavioral flexibility requirements incorporating

both trait and situational elements of leadership and

respond accordingly (Zaccaro, Foti, & Kenny, 1991).

High SMs are also more likely to hold more leadership

positions (Day, et al., 2002; Zaccaro, et al., 1991).

Since high SMs appear more effective socially

by reading and responding to interaction cues, researchers

hypothesized in a study of emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1995) that SM is a moderator of conscientiousness

and performance and should be controlled as a variable

due to the overlap of the emotional intelligence constructs

(Douglas, Frink, & Ferris, 2004). Douglas, Frink, and

Ferris (2004) also found high SM was positively correlated with rating of performance and negatively related

to age, though not with conscientiousness or emotional

intelligence.

Mehra, Kilduff, and Brass (2001) found a direct

relationship between high SM and performance. In

research involving performance appraisal from various

sources (self, peer, and supervisors), both in student work

groups and in a study of project teams in corporations,

high SMs rated themselves significantly higher than low

SMs; only in student groups did low SMs ratings reflect

their greater consistency of behavior which supported

their hypotheses (Miller & Cardy, 2000). In other situations, high SMs received higher supervisory performance

appraisals from supervisors than low SMs in boundary

spanning roles (Caldwell & O’Reilly, 1982) and low

SMs showed behavioral consistency and received higher

performance ratings from their supervisors (Caliguri &

Day, 2000).

In a study of turnover intentions, self-monitoring

accounted for previously unexplained variance beyond

traditional predictors of satisfaction and commitment:

degree of job satisfaction was a better indicator of intent

to leave for high SMs and commitment was a better for

low SMs (Jenkins, 1993).

Kilduff and Day (1994) tracked MBA graduates

over five years and found that high SMs were more likely

to change employers, move to different geographic locations, and achieve cross-company promotions than low

SMs. The high SMs who stayed with an organization got

more promotions than low SMs during that same period.

They concluded that high SMs pursue more successful

Volume 9, 2006

managerial career strategies than low SMs by being able

to adapt to circumstances and opportunities (Kilduff &

Day, 1994).

Particularly with regard to personnel selection,

there is a reliance on appearance and personality (Snyder, Berscheid, & Matwychuk, 1988). Tasks involving

selection decisions from an evaluator’s viewpoint showed

that interviewers who are high SMs focus more on job

candidates’ appearances and low self-monitoring interviewers focused more on the job candidates’ personalities

(Snyder et. al. 1988). Dobbins, Farh, & Werber (1993)

found a self-monitoring effect on the job search process,

with high SMs more likely than low SMs to portray

themselves as best suited to workplace situations (Miller

& Cardy, 2000).

HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

The interview is perhaps the most widely used

selection approach in organizations and provides a

forum in which applicants have only a brief time to

present themselves as a prospective employee. Impressions made during this critical face-to-face time period

have immediate and lasting consequences. With the

high SM’s tendency to develop their self-presentation

behaviors, they seem more likely to make a stronger

impression during in an interview situation than low

SMs. The advantage of this personality tendency may

be relatively pronounced if all job candidates are similar on other factors (e.g., education, background, work

experience, etc.).

High SMs seem to have a number of advantages

in an organizational environment. This leads one to

hypothesize that receiving the opportunity to use that

personality trait may begin with the selection process

itself. As long as interviews are used, high SMs could

present themselves as a better fit or job match than low

SMs, which may result in more favorable outcomes.

Three hypotheses were tested in this study:

(1) First, it was hypothesized that self-monitoring accounts for significant incremental

variance in the number of second interviews granted to the job seekers beyond

the variance due to demographic and

background variables, with self-monitors

receiving more second interview opportunities.

(2) The second hypothesis was that selfmonitoring would account for a significant

amount of variance in the number of job

offers extended to candidates, beyond

that accounted for by demographic and

13

Palmetto Review

Kimberly Freeman

(3)

background variables.

Thirdly, it was hypothesized that selfmonitoring would explain a significant

amount of variance over demographic and

background variables for the early job acceptance measure of job search success.

search success: (1) the number of second interview opportunities the student had received, (2) the number of job

offers extended, and (3) whether the subject had accepted

a job offer at least two weeks before graduation.

RESULTS

METHOD

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations

and intercorrelations matrix for the demographic and

background variables used in the study.

Subjects

Ninety-seven second-year MBA students in a

private southeastern university participated in the study.

A total of 40 subjects completed usable questionnaires,

resulting in a response rate of 41.2%. Among those who

responded, 35% were women, the average age was 26.5,

and the average months of work experience was 36.2.

All forty subjects were seeking employment through the

MBA placement office.

TABLE 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations for

Demographic and Background Variables, and

Self-Monitoring scale

Measures

Demographics and background. Data on

gender, age, months of work experience (MWE), undergraduate grade point average (UGPA), a standardized

test score (GMAT), and graduate-level grade point average after three semesters (GPA3) were made available

by the administration for use as predictor variables. It

should be noted that undergraduate GPA was based on

the traditional 4.0 scale, while the graduate-level GPA

was scaled from 0.0 to 8.0.

Self-Monitoring Scale. The subjects completed

a 25-item self-report measure of true-false questions on

self-monitoring behavior and scores could range from 0

to 25. The self-monitoring scale (SMS) was developed

by Snyder (1974) and has been used extensively (Gangestad & Snyder, 2000; Snyder & Gangestad, 1982). High

test-retest reliability, internal consistency, reliability, and

validity of the SMS scale have been well established

(Snyder & Gangestad, 1986; Snyder, 1987). Examples

of SMS scale questions that reflect high self-monitors

include “Even if I am not enjoying myself, I often pretend to be having a good time”; “In different situations

and with different people, I often act like very different

persons”; and “I’m not always the person I appear to be.”

Low self-monitors would tend to respond positively to

“I find it hard to imitate the behavior of other people”;

“I have trouble changing my behavior to suit different

people and different situations”; and “My behavior is

usually an expression of my true inner feelings, attitudes,

and beliefs.”

Job Search Success measures. Two weeks

prior to graduation, the MBA placement office provided

the information for the three dependent measures of job

Volume 9, 2006

Measure

M

SD

2

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

26.5

36.2

2.92

594

6.42

12.83

4.02

40.21

0.36

41.91

0.46

4.13

.94*** -.33*

--.36*

--

Age

MWE

UGPA

GMAT

GPA3

SMS

3

4

5

6

-0.22

-0.16

0.25

--

-0.23

0.21

0.14

0.1

--

0.06

0.1

-0.2

-0.13

0.1

--

N=40.

Note: MWE is Months Work Experience, UGPA is Undergraduate Grade

Point Average. GMAT is Graduate Management Aptitude Test, GPA3 is

Grade Point Average after 3 semesters in the MBA program; and SMS is the

Self-monitoring scale.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** < .001.

***p

Relationships among Demographic and Background

Variables and Self-monitoring

There were no gender differences on any of the

variables, thus gender was not included in the analysis.

As would be expected, age was strongly related to months

of work experience. Undergraduate GPA was negatively

correlated with both age and MWE, as would also be

predicted. Neither GMAT nor graduate-level GPA was

significantly correlated with any of the other variables in

the study. Age ranged from 22 to 40 years old, months of

work experience (MWE) ranged from 0 to 152 months,

undergraduate GPA for the students ranged from 2.1

to 3.7 (based upon a 4.0 scale), GMAT scores ranged

from 510 to 700, and GPA after three semesters in the

MBA program ranged from 5.63 to 7.58 (based upon

an 8.0 scale). Scores on the SMS ranged from 5 to 24

and were not correlated with any of the demographic or

background variables.

Relationships among Self-monitoring and Job

Search Success Measures

The three measures of job search success were

14

Palmetto Review

The Role of Self-Monitoring in Job Search Success: A Field Study

highly intercorrelated. The number of second interviews

was strongly related to both number of offers and early

job acceptances. As would be expected, whether one had

accepted a job offer by two weeks prior to graduate was

strongly related to the number of offers received by the

subject. Table 2 shows these correlations.

On step two, the self-monitoring variable was

entered into the regression equations to assess the incremental variance it explained in the dependent measures

beyond those entered into the equation on the first step.

The hierarchical regression results are presented in Table

3. Results for the number of second interviews are given

first. As shown, self-monitoring accounted for significant

variance in the number of second interviews beyond that

accounted for by variable entered in the first step (Delta

R-squared = .39), F

F(6,33) = 22.91, p < .0001.

TABLE 2

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations for Self

Monitoring and Dependent Variables

Measure

1. SMS

2. Second Int.

3. Offers

4. Accept

M

12.83

2.15

0.98

0.58

SD

4.13

1.27

0.86

0.5

2

.63***

--

3

.43**

.56***

--

4

.36**

.47**

.75***

--

TABLE 3

Hierarchical Regression Analysis controlling for

Demographic and Background Variables with Main Effect

(Self-Monitoring) entered in Step 2 for Prediction of

Second Interviews, Job Offers, and Early Job Acceptance

N=40.

Note: SMS is Self-Monitoring Score, Second Int. is for number of second

interviews, Offers is for number of job offers, and Accept is for early job

acceptances.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Job Search Success Measures

Second

Job Offers

Interviews

Betas

Betas

Step 1:

Control

variables

Age

MWE

UGPA

GMAT

GPA3

R-squared

Relations among Self-Monitoring and Other Variables

Self-monitoring was related to all three of the job

search success measures. Self-monitoring was strongly

correlated with number of second interviews (r = .63, p

<.001) and with the number of offers extended (r = .43,

p < .01), and moderately correlated with early job acceptance (r = .36, p <.05).

Step 2:

SMS

R-squared

Delta

R-squared

Tests of the Hypotheses

The hypotheses were tested by examining the

incremental variance explained by self-monitoring over

the demographic and background variables. Two-step hierarchical regression analyses were conducted using each

of the job search success measures as the criterion.

On the first step, the demographic and background variables entered simultaneously were: age,

MWE, UGPA, GMAT, and GPA3. It was expected that

age, grades, test scores, and work experience would

explain some of the variance in the job search success

measures for several reasons. Since past performance is a

good predictor of future performance, it would seem that

high grades and test scores would be important indicators

of job search success as indicators of ability, perseverance, and/or a willingness to work hard. Further, age and

work experience would likely indicate a higher level of

maturity and experience in assimilating into the work

environment. Thus, it was felt that these variables should

be controlled prior to entering the variable relevant to the

hypotheses: self-monitoring. However, the demographic

and background variables which were entered at step 1

did not account for a significant amount of variance for

any of the three dependent variables.

Volume 9, 2006

-0.11

0.01

0.58

0

0.2

Early Job

Acceptance

Betas

-0.07

0

-0.22

0

-0.1

0.06

0.2

-0.04

0

-0.14

0

0.02

0.09

0.09

0.13

0.04

.45*

0.27

0.25

.39***

.18**

.12*

N=40.

Note: MWE is Months Work Experience, UGPA is Undergraduate Grade

Point Average. GMAT is Graduate Management Aptitude Test, GPA3 is

Grade Point Average after 3 semesters in the MBA program, and SMS is

Self-monitoring Scale.

Note: Beta values are for full model.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Results for offers extended were similar to those

for second interviews. Self-monitoring accounted for a

significant amount of variance beyond the demographic

and background variables alone (Delta R-squared = .18),

F(6,33) = 8.33, p < .01.

F

The results with regard to early job acceptance,

the third measure of job search success, were also

significant ((F

F(6,33)

F

(6,33) = 5.52, p < .01). Self-monitoring

accounted for an additional 12% of variance beyond the

demographic and background variables alone.

15

Palmetto Review

Kimberly Freeman

DISCUSSION

Graf & Harland (2005) used MBA students in

a study of effective screening and selection of expatriates and found that interpersonal competence measures,

which included a communication skills component,

predicted intercultural decision quality in an intercultural

organizational scenario.

One of the top recommendations by Bernthal

and Wellins (2006) was to base selection and promotion decisions for leaders on interpersonal skills and

personal qualities. The lack of these skills and qualities

being the two most common reasons for failure of leaders despite being promoted based on the leader’s ability

to get results.

Although McFarland, Ryan, and Krista (2002)

did not directly evaluate self-monitoring behavior, they