Strategies for Regulating Use of Forest Resources: How Exclusive? Indiana University

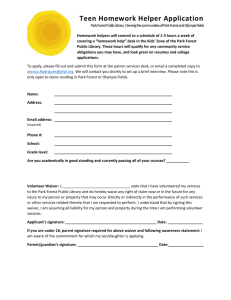

advertisement

Strategies for Regulating Use of Forest Resources: How Exclusive? Amy R. Poteete Indiana University Comments welcome: apoteete@indiana.edu Paper presented at a colloquium at the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University, Bloomington, on 8 October 2001. © Amy R. Poteete 2001. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 1 Strategies for Regulating Use of Forest Resources: How Exclusive? Amy R. Poteete 1 Indiana University ABSTRACT: Regulation of renewable natural resources involves restriction of resource use, either by limiting extraction by each resource user, limiting the number of resource users, or both. The choice between distribution and exclusion affects the distribution of resource flows, and thus impinges upon political, economic, and social relations. Research on natural resource management and the organization of agrarian societies identifies a number of factors likely to influence the inclusiveness of strategies for resource management: demand for the resource, the difficulty of defending the resource, risk and risk aversion, local conflicts, the presence of marginal groups, and the political opportunity structure. This paper focuses on the probability of exclusionary tactics of forest management. Analysis of data from the International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) research program suggests that political relations among resource users and between resource users and outside authorities are the most important predictors of exclusionary efforts by local actors. Economic theories of property rights predict that people will respond to increasing scarcity and/or deteriorating resource conditions by striving to define property rights more clearly (Alchian and Demsetz 1973). Market penetration, technical change, and population growth are but a few of the factors that alter relative prices and prompt efforts to define or alter property rights (ibid; Anderson and Hill 1973; Ensminger1992; North 1981; cf., Hyden 1983). Because the definition of property rights bounds access, the process is widely understood as one of exclusion. Indeed, instances of exclusion 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2001 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Hilton San Francisco and Towers August 30 - September 2, 2001. A grant from the Ford Foundation to the International Forestry Resources and Institutions research program at Indiana University supported this research. Comments from Abwoli Banana, Clark Gibson, and Catherine Tucker contributed to the quality of this paper; I bear full responsibility for its remaining flaws. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 2 abound (e.g., Agrawal 1999, 67 ff.; Ensminger 1992, Chapter Five; Norberg 1988; Peters 1994). Yet many groups or communities instead limit access by regulating the quantity and distribution of resources harvested rather than by reducing the number of harvesters (e.g., Agrawal 1999, 52 ff., Dayton-Johnson 2000; McKean 1992; Scott 1976).2 What accounts for the choice of strategies for resource management? The balance between limiting harvest size and the number of resource users reflects current power relations in a society. Because these choices alter resource flows, they also contribute to the evolution of political, economic, and social relations. Baland and Platteau (2000 [1996]; cf., 1998) argue that exclusion occurs only if a clearly identifiable subset of resource users exists, such as immigrants or some lower status minority. Otherwise, risk aversion leads current resource users to reject exclusion for fear of being among those excluded, and opt instead for rules for sharing that restrict total resource use. Local understandings of community often exclude migrants, nomads, women, youth, marginalized ethnic groups (e.g., indigenous populations), or lower castes. Restrictive definitions of community or marginality within a community can provide a basis for exclusion (Berry 1993, 117; Ensminger 1992, 133-4; Netting 1981; 78-9). Although strangers and lower status groups are frequently enough treated as scapegoats, heterogeneity also exists among groups that choose to redistribute resources rather than exclude lower-status groups. Even if social or political status offers a good predictor of which subsets of resource users are most likely to be disadvantaged, it does not provide much insight into the choice of exclusion over quantity or access restrictions. 2 Failures to develop any system of regulation also occur, resulting in resource degradation (Hardin 1968). This paper focuses on the nature of change in systems of regulation that already exist. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 3 Other factors that may affect this choice include environmental risk, attitudes towards risks, the costs of monitoring and enforcing exclusion, the number of relevant forms of heterogeneity, the relative organization of different sub-sets of resource users, representation of various interests in decision-making bodies, and relations among the various groups involved in resource use and management. This paper is part of a larger project that evaluates the relative importance of a variety of factors likely to affect the relationship between institutions and equity: demand for the resource, ease of defending the resource, the degree of risk and risk aversion, the presence of conflicts, the presence of marginal groups, and the externally defined political opportunity structure. As a first step, I analyze the association between efforts to exclude others from resource use and indicators of each of these factors. Analysis of data on forest conditions, the people who use those forests, and their institutions for managing forest resources in Africa, Asia, and the Americas suggests that exclusionary actions are not mere reflections of perceived increases in scarcity or levels of heterogeneity among forest users. Political relations among groups within a community and between subgroups and outside authorities are more important predictors of redistribution and exclusion. Choosing Between Restrictions on Extraction and Exclusion Maintenance of renewable resources depends upon regulation of extraction to allow regeneration. Resource use can be limited by restricting either the number of resource users or the amount extracted by all resource users. When changing conditions or patterns of use threaten maintenance of the resource base, the number of people allowed to use the resource may be reduced while the amount extracted by each person POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 4 remains unchanged, or the amount extracted by each person may be reduced while the number of people allowed to use the resource remains unchanged. Intermediate options combine exclusion with redistribution. 3 Strategies of exclusion alter the definition of property rights. The focus on the emergence of property rights in the economics literature presents this process as one of specifying rights to resources more clearly (Alchian and Demsetz 1973). The dynamic of sloughing off “excess” users also occurs where systems for resource management already exist. Reduction of the set of individuals with recognized rights to a resource may involve clarification of rights, but is as likely to involve redefinition of rights that were clear all along. The degree of constriction and inequity involved in exclusionary tactics varies. Exclusion often involves individualization of rights, although collective management may continue with a more narrow definition of group membership. The smaller the reduction in the number of resource users, the more important are quantity restrictions for reducing total extraction. 4 Either way, changing a system for resource management directly affects the distribution of resources. As such, it is inevitably a political process. At least three broad categories of hypotheses about the choice of exclusionary versus distributive strategies for managing natural resources can be distilled from the diverse literature on property rights and social arrangements in agrarian societies. They relate to demand for the resource relative to the difficulty of defending access to it, 3 Total exclusion is also an option. Nationally designated protected areas often restricted all harvests, at least prior to the spread of community-based programs. Some communities completely curtail harvests in a portion of their forest, designated fisheries, or part of the range. Select forms of use may persist, as when medicinal herbs are collected from sacred groves but trees left intact. In other cases, harvests resume after the resource regenerates. This paper focuses on decisions about how to divide a resource; it does not systematically consider instances of total exclusion. 4 Neither exclusion nor redistribution guarantees maintenance of a renewable resource. When externalities are important, exclusion may remove rather than improve incentives for maintaining resources. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 5 concerns about risk, and aspects of the political environment such as conflicts, the existence of marginal groups, and the overarching political opportunity structure. Demand for the Resource and Difficulty of Defense The value of a resource relative to the cost of defining and defending rights over it affects the degree of exclusion in property rights. Both exclusionary tactics and efforts at redistribution seem unlikely to occur unless demand for a resource is relatively high. Changes in population density and productive technology alter the value of and demand for resources. Neoclassical economists expect individuals to respond to increases in scarcity or productive value by attempting to establish more exclusive rights over valuable resources (Alchian and Demsetz 1973). 5 Specification of property rights more clearly defines the rights of some set of individuals to access and use resources, but also defines the terms for excluding others. Shifts in relative prices may be the primary motivation for seeking clearer specification of property rights, but outcomes can be understood only by recognizing the frictions arising from transaction costs (North 1981, 1990). Among the more important transaction costs affecting changes in property rights are those associated with the relative ease of defending a resource, the legitimacy of and thus willingness to comply with new arrangements, and the degree of external legal backing for changes. At high population densities, although the value of the forest increases, more severe collective action problems may thwart efforts to protect forest resources through exclusion or other means. Very high levels of demand may undermine the feasibility of improving the condition of forest resources through institutional change (cf., Ostrom 5 Perceived scarcity also affects evaluations of non-consumptive values associated with forests. Many nonconsumptive values are public goods, but some are amenable to exclusionary strategies of management. Limited access to a forest may, for instance, enhance its value as a refuge from the bustle of daily life. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 6 1999). Population pressure also affects the severity of collective action problems. Following Olson (1965), many researchers believe that small group size raises the probability of successful collective action. The smallest groups, however, exert less pressure upon the sustainability of their forest resources and thus have less need to act collectively to alter their system for resource management. The value of concerted action to tighten regulation of resource use increases with population pressure, but so does the severity of collective action problems. Even if smaller groups would benefit from tightening regulation of resource use, they may lack the resources needed to enforce tighter rules (Agrawal and Goyal 2001). These sorts of countervailing pressures suggest a curvilinear relationship between population pressure and changes in the regulation of natural resources. Once efforts at exclusion occur, effectiveness in reducing resource use depends on monitoring and enforcement (Agrawal and Yadama 1997, 455; Anderson and Hill 1977; Bruce and Migot-Adholla 1994). The costliness of monitoring and enforcement depends upon the nature of the resource, including its size, spatial distribution, and predictability (Ostrom 1999; Ruttan 2001; Schlager et al. 1994); technologies for observation and enforcement (Anderson and Hill 1977; North 1981); and institutional arrangements. The cost of defense is non-negligible for extensive resources, resources with obscured visibility, and mobile and unpredictable resources. Changes in technology that facilitate defense of valuable resources can be expected to prompt moves from cooperative to exclusionary tactics in resource management, such as followed the introduction of barbed wire in the American West (Anderson and Hill 1977). POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 7 The legitimacy of strategies for regulating resource use arises out of local political conditions, including historical changes in relations among social actors. Likewise, external legal backing for patterns of resource use and decisions about resource management depend upon the overarching political context. These explicitly political factors are discussed at greater length below. Risk and Risk Aversion According to the transaction costs approach, common property persists despite its inefficiency because the costs of negotiating and enforcing more restrictive property rights outweigh the benefits (North 1981, 26; cf., Baland and Platteau 1998, 645). But even before taking transaction costs into consideration, the distribution of resources within collective property arrangements meets or exceeds the efficiency achieved through exclusion under some conditions. Economies of scale create diseconomies in monitoring that limit the value captured through exclusionary tactics. Depending upon the nature of the resource, environmental conditions, and technologies of production, collective management may reduce the costs associated with monitoring and enforcing exclusion, offer insurance against risk, achieve economies of scale or of scope,6 or facilitate coordination with complementary aspects of production (Baland and Platteau 1998, 645 – 646; Netting 1981, 68 – 69; Quiggin 1993). Each of these factors increases the value of collective management. Cooperative systems of resource management are widely understood as responses to environmental and economic risk. Ecological risk, when spatially distributed, encourages use of resources on a larger scale. In arid rangelands, for example, utilization 6 Economies of scope exist when production of several goods jointly costs less than production of the same goods by separate firms (Baumol, Panzar, and Willig 1982). POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 8 of grazing over a large territory can compensate for spatial and temporal variability in rainfall and the quality of forage (Behnke and Scoones 1993; Dyson-Hudson 1985; Western 1982). Ecological variability and the economic risk to which it gives rise also encourage collective or reciprocal arrangements for resource management as ways to spread risk. Social arrangements in many rural societies have been characterized as moral economies, or more generally as systems for spreading risk in subsistence economies (Scott 1976, cf., Berry 1993; Hyden 1983). Risk may be natural in origin (e.g., floods, droughts, plague, infestation), related to personal position (e.g., health, the ratio of household size to productive assets), or arise from systemic factors (e.g., proportional taxes or systems for allocating productive resources). The proximity of the poor to the subsistence threshold produces a strong aversion to risk. The poor adopt productive strategies that reduce risk, such as the use of multiple varieties of seeds or breeds and the use of multiple ecological zones. But they also maintain social arrangements that reduce risk, such as reciprocity, communal management of land, and labor exchanges (Scott 1976, 3 and 5; cf., Berry 1993). Even when individuals have the physical and legal ability to exclude others, the presence of substantial ecological, economic, or personal risk encourages the adoption of reciprocal strategies instead (cf., Rawls 1971; Segosebe 1997, 290 - 293). Political Context: Local Conflicts and Supra-Local Political Opportunity Structure Choices among strategies for regulating resource management reflect more than the economics of demand and defense and the political economy of risk. Efforts to alter systems for resource management cannot escape the general political context in which POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 9 they occur. The dynamics of collective decision-making reflect relations among the people who use the resource base, particularly conflicts involving distinctive or marginal groups, as well as relations between the local community or polity and larger-scale political entities (e.g., “the state”). Even when collective management is economically efficient, challenges of regulating resource use must be addressed. Regulation through redistribution would seem a natural strategy for groups with established systems for collective resource management, but exclusion remains a viable option. Indeed, the transaction costs of defending private property encourage strategies of partial exclusion. Limiting the number of excluded people relative to those still using the resource lowers the costliness of enforcement, especially if excluded individuals are not organized. If the resource base can be maintained by excluding fewer than half of the beneficiaries, those who retain access will have an interest in supporting the change while those excluded may be unlikely to prevent it. But this calculus assumes common knowledge of the identity of individuals to be excluded. Unless a clear sub-group can be targeted for exclusion, the majority may oppose partial exclusion because of the possibility of being among those excluded (Baland and Platteau 2000 [1996], 204 ff.). Despite the rhetoric of community unity, even small-scale polities contain diverse populations. Conflicts within a group can hamper collective action, or promote action that disproportionately benefits subsets of the polity. Not all forms of social heterogeneity give rise to politically relevant conflict. The presence of both exclusionary and redistributive arrangements within highly unequal societies lead Baland and Platteau to conclude that the degree of exclusion is not a function of inequalities in wealth (1999, POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 10 785). Gibson and Koontz argue that homogeneity in values is more important for cooperative resource management (1998, 622-623). The substantive form of heterogeneity may be less important than the number of dimensions along which internal heterogeneity occurs (Quiggin 1993, 1130 – 1131). 7 Conflicts can be expected to affect strategies for resource management through two dynamics. First, conflicts may hinder the ability to achieve the level of collective agreement needed to alter systems of resource management. The level of agreement needed to achieve effective collective decisions influences the significance of conflict. When consensus or the support of a super-majority is required, conflict within a group quickly becomes an obstacle to efforts to alter resource management, whether through exclusionary or other means. Otherwise, conflict undermines more inclusive arrangements and provides motivation for exclusionary tactics. When rigid manifestations of heterogeneity yield distinctive communities within a polity, decisions about resource management reflect and contribute to political relations among these groups. When dominant groups depend upon cooperative relations with poor and less organized groups to a considerable extent, they may retain or institute inclusive arrangements for resource management even when they have the legal and political wherewithal to impose exclusionary policies (cf., Scott 1976). Similarly, even in the absence of degradation, a politically dominant group may adopt a biased strategy of resource regulation in response to challenges, or as a way to head off such challenges (cf., Agrawal 1999, 53-7). Neither outcome would make sense unless the broader political dynamics were taken into consideration. 7 Cf., formal models that show how multi-dimensionality constrains the probability of stable social choices, as reviewed by Ordeshook (1986, 166 – 175). POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 11 Inequities in organization and access to resources affect the ability to mobilize. The majority rarely manages to exclude wealthy and well-organized minorities while minorities sometimes exclude politically and economically marginal groups (Baland and Platteau 1998, 648). The presence of at least one marginal group appears to increase the likelihood of efforts to regulate resource use through exclusion. Mobile groups can be expected to face additional disadvantages, at least when other resource users lead relatively more stationary lifestyles. Transience sets mobile populations off from sedentary residents, marking them as precisely the sort of easily identifiable sub-group vulnerable to exclusion. Interactions between sedentary and mobile populations occur during limited periods and are of an intermittent nature, whereas interactions within each population are more likely to be complex and on-going. Consequently, social capital within each group facilitates cooperation, but the networks linking the groups together are few and fragile (cf., Fearon and Laitin 1996, 725 ff.). If patterns of resource use by mobile and sedentary populations differ, neither group may fully appreciate economies of scope that encompass both sets of productive activities (Quiggin 1993). Geographicallybased institutions for decision-making further favor stationary groups, lowering their costs of participating in decision-making while raising the costs of participation for mobile groups. If exclusionary efforts typically target distinctive marginal groups, mobile populations seem to be particularly at risk. Ultimately, local decisions about resource management confront external political authorities. National and regional laws, institutions, and political dynamics define the political opportunity structure within which local-level decisions get made. The distribution of formal authority by the overarching legal framework sets obstacles of POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 12 varying heights before social groups wishing to influence practices at the local level. Relations between local and larger-scale actors can be seen as nesting, substitutive, or conflicting. Nesting occurs when laws and institutions at larger-scales reinforce those at smaller-scales of social organization (Ostrom 1990, 101-2). Although devolution of decisions to the lowest feasible level (given externalities) of social aggregation has much to commend it, external authorities preempt local decision-making all too frequently. If external authorities have the capacity to enforce their decisions, local actors have less incentive to mobilize to alter arrangements for resource management themselves. Withdrawal of legal backing undermines locally based decisions. In the absence of external backing, local decisions depend on strong local agreement or effective informal arrangements for enforcement (Ghate 2000). In Pursuit of Many Cases The overarching political context may trump other factors, but it does not make them irrelevant. Any effort to understand decisions about resource management should consider the value of the resource, the difficulty of defending access to the resource, concerns about risk, and the general political environment. Each of these explanatory factors actually represents a number of distinctive variables. Any statistical analysis of choices among strategies for managing renewable resources confronts the problem of needing data on a large number of cases. The International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) Database The International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) research program offers a large cross-national database that makes feasible multivariate analysis of questions related to local-level resource management. Founded in 1993, IFRI is a POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 13 network of collaborating research centers using a common set of methods to study forests, the people who use forest resources, and their institutions for resource management. The relational database captures the connections among forest systems, sets of resource users, particular forest products, formal and informal rules for resource use, and formal local and supra-local organizations. By the middle of 2001, the IFRI database included data on 141 sites with 231 forests, 233 user groups, 94 forest associations, and 486 products. The large number of cases represented in the IFRI database allows analysis of complicated social and biological phenomena affecting natural resources and their management. IFRI offers a wealth of data related to strategies for resource management. The database includes substantial historical background on particular forests and the people who use them, as well as overviews of policies affecting forest use. Despite these advantages, the IFRI database was not designed to investigate whether strategies for modifying systems of resource management are exclusionary. Rather, IFRI grew out of efforts to understand successes and failures in collective management of natural resources (Ostrom 1990; Ostrom et al. 1994). This research tradition identifies characteristics of groups associated with the development and survival of institutions for managing renewable resources held in common, and furthers our understanding of interactions among these characteristics. When one’s central research questions concerns collective action within groups of individuals who use natural resources, it makes sense to collect data with such groups as the main unit of analysis. Thus, the basic social unit of analysis in IFRI is the user group, defined as a set of individuals with the same rights and responsibilities to forest resources. This definition does not require formal organization or collective action, since these features are POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 14 potential dependent variables. When residents of a settlement have differing rights and responsibilities to forest resources, IFRI sees multiple user groups and records data for each. A group with common rights and responsibilities to a forest may be homogeneous or heterogeneous on many other dimensions with social and political relevance. This strategy for data collection allows analysis of relationships between diverse forms of social heterogeneity and collective action within groups with comparable rights to resources. The IFRI database contains data relevant for the study of exclusionary tactics for resource management, but often in forms that are not immediately suitable for analysis. Relations among user groups utilizing the same forest resources, for example, are not immediately apparent. The structure of the database does not automatically capture links among user groups or between user groups and associations (i.e., more explicit organizations). These relationships can be reconstructed to some extent by drawing upon an interorganizational inventory. Questions about conflicts with people outside each group are also helpful in this regard. Operationalization When conducting analysis with a relational database, a case is not always – or even often – simply a site. Instead, a case is defined by the relationship of interest. For this analysis, a case is a user group – forest product – forest relationship. The possibility of multiple relationships among entities means that the number of cases in a given analysis can be larger than the number of records about any given entity. Data from 353 user group – forest product – forest relationships are used in the analysis. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 15 Extensive information about current rights to forests and particular forest products can be found in the IFRI database. No existing variable, however, explicitly addresses efforts to modify rules for forest use through exclusion. A dichotomous dependent variable for this analysis was created by coding mentions of exclusionary efforts by a user group in long text fields describing the history of each user group, noteworthy changes in user groups, and changes in the policy environment that affect the forest. Since none of these fields request information about exclusionary efforts, the dependent variable most likely under-represents their frequency. On the other hand, exclusionary efforts require considerable organizational investment and involve significant political cost. The conflict associated with efforts to exclude others increases the likelihood that research teams would notice and record such information. Examples of exclusionary actions include the definition of restrictions on entry by forest management committees or voluntary organizations formed on the initiative of local resource users, privatization, attempts to curtail uses of forest products that were informally recognized in the past but lack legal standing, and the displacement of subsets of local resource users following violent clashes. Measures of demand were more readily available. The value of forest resources increases with population pressure, commercial value, and evidence of resource depletion. The value of the forest at low population densities is unlikely to prompt efforts to exclude others. The number of individuals in the user group per hectare of forest provides a measure of population density (POPPRESS). The inclusion of population pressure and population pressure squared (POPPRESS2) in the analysis tests for the possibility of a curvilinear relationship. The proportion of individuals in each user group POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 16 who depend significantly upon the forest for income related to commercial activities provides an estimation of the commercial significance of the forest (COMMERCE). IFRI provides a number of measures of forest condition. Since some delay can be expected between evidence of degradation and action to defend forest resources, the number of species reported as having disappeared over the past twenty years seemed the most appropriate (LOSTSPECIES). The difficulty of defending forest resources is expected to increase with both the size of the forest and the distance of the user group from the forest. The size of the forest is recorded in hectares (SIZE). The average distance of the user group from the forest (DISTANCE) has been classified as being within 1 km, between 1 – 5 km, between 5 and 10 km, and more than 10 km. Since proximity to the forest facilitates monitoring of forest use, greater average distance should make exclusionary strategies more difficult to enforce. IFRI offers measures of ecological and economic risk. Predictability of annual resource availability has been recorded for each product on a five-point scale (ECORISK) that ranges from no to dramatic year-to-year variation. Economic risk is measured both positively and negatively. The proportion of individuals in each user group with full-time employment (EMPLOYED) should indicate a relatively low degree of economic risk. 8 Dependence on the forest for subsistence suggests the sort of proximity to the subsistence threshold associated with risk aversion. The proportion of individuals in each user group that depends significantly on the forest for subsistence (SUBSISTENCE) measures the likely prevalence of such concerns within each user group. 8 Wage employment can raise economic risk if continued employment is undependable (Baland and Platteau 1999, 775; Scott 1976, 35 ff.). Full-time employment is interpreted as an indication of relative stability. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 17 Several variables capture aspects of the political context in which decisions about exclusion occur. The severity of conflict within a user group is measured on a four-point scale that ranges from no conflict to the presence of conflict that disrupts normal activities (CONFLICT). Exclusionary efforts are expected to be less common when conflict within a user group has become disruptive. No single existing variable adequately captures conflict between a user group and other groups. This information was gleaned from long text fields describing changes in policies affecting forest management and the effects of conflicts among user groups upon use of the forest. A dichotomous variable indicates whether any inter-group conflict was mentioned (INTERGCONFL). To the extent possible, this measure distinguishes among the various user groups associated with each forest and limits positive scores to those actually involved in conflicts. Three indicators of distinctive groups are included. One dichotomous variable (MOBILE) indicates whether mobile groups use a forest. Another (WEALTHDIF) measures whether great wealth differences exist, according to local definitions of wealth and poverty, among households in the user group.9 The third (PARTRULE) identifies situations in which some but not all members of a user group participate in making decisions about management of forest resources. Three dimensions of relations with state authorities are also represented. Mentions of government action to exclude some or all people from use of forest resources appear in long text responses about shifts in the policy environment and the history of user groups. A dichotomous variable (GOVEXCLU) indicates whether external authorities had taken 9 The structure of the data does not allow assessments of wealth differences among individuals or households who use the forest but belong to different user groups. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 18 any exclusionary action. Exclusionary government action preempts or overrides exclusionary efforts by forest user groups. Communal tenure should offer user groups the greatest authority to alter the rules for using forest resources without external interventions. A dummy variable indicates ownership of a forest by a village or part of a village (COMMUNITY).10 AMBIGLAW indicates situations in which resource use by user groups lacks legal recognition but is not explicitly illegal. This sort of legal ambiguity offers opportunities for user groups to attempt to redefine their rights to resources. Efforts at excluding others are expected to be most common when the legality of resource use is ambiguous. Regulation of Natural Resources: More Political than Economic The analysis suggests that, of the three broad categories under consideration, political factors outweigh cost-benefit calculations and risk in local-level strategies for regulating natural resources. Demand for forest resources and the difficulty of defending them are important, but not determinant. The role of risk, if any, is ambiguous. Local political factors are important and robust predictors of efforts to exclude others from the use of forest resources, but the externally defined political opportunity structure emerged as the most important and predictor of exclusionary action. The results of the logit model,11 reported in Table One, demonstrate that efforts at exclusion cannot be attributed to any one set of factors, but that political conditions are the most important predictors of exclusionary action. Demand for forest resources, ease of defense, risk, political conflict, and legal status all affect the probability that a user 10 Although labeled COMMUNITY, this variable does not encompass all forms of collective management. In particular, this variable does not count forests owned by cooperatives, religious orders, or corporations as communal. 11 Expectation of a non-normal distribution prompted use of a logit model. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 19 group will attempt to exclude others from use of forest resources. Indicators within each category of independent variables differ considerably in importance. Population density, the external political context, and the disruptiveness of conflicts emerge as the most important predictors of efforts to exclude others from forest resources. The results affirm the importance of demographic pressures, but also the essentially political nature of exclusionary actions. Modifications of the model to check for robustness (see Appendix) confirm that the most important factors are political. [Insert Table One about here] Demand and Defense: Important but not Determinant Among the indicators of demand for forest resources, only population density and its value squared reach levels of statistical and substantive significance. The significance of both variables and their signs confirm the curvilinear nature of the relationship with exclusionary action. The probability of exclusionary efforts increases with moves from low to moderate population density, but decreases with moves from moderate to high population density. The decline in efforts at exclusion at high population densities may reflect the growing difficulty of collective action in larger groups (Olson 1965). Or higher population densities may coincide with levels of degradation too high to justify exclusionary efforts (cf., Ostrom 1999). An increase in the proportion of a population that depends upon forest resources for income from commercial activities was expected to increase the likelihood of exclusionary action, as was an increase in the number of species noted as having disappeared over the past twenty years. Not only are these measures statistically and substantively insignificant, the directions of the relationships are opposite that predicted. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 20 A change from 0 to 1 in the proportion of a user group with commercial interest in the forest corresponds with a meager decline in the likelihood of exclusionary effort of 0.07 – an effect statistically indistinguishable from 0. The likelihood of efforts to exclude declines by 0.32 with an increase from 0 to 15 in the number of species noticed as having disappeared from a forest over the past twenty years. Although substantively sizeable, the relationship is not statistically significant and even the direction of the relationship lacks statistical stability. Perhaps species disappear too rarely to make this a useful indicator of resource deterioration. Exclusionary action may be more likely when degradation is evident but species have not actually disappeared. The model includes two indicators of the difficulty of defending forest resources: the size of the forest and the average distance of residences from the forest. As expected, the likelihood of exclusionary action declines as the average distance from the forest – and thus the difficulty of monitoring forest use – increases. A shift in the average distance of residences from the forest from within 1 km to more than more than 10 km corresponds with a decline of 0.19 in the likelihood of exclusionary action by a user group. Contrary to expectations, however, exclusionary action grows more likely as forest size increases. An immense increase in forest size, from 2 to 22,700 hectares, is needed to increase the probability of exclusion by 0.22. Nonetheless, the association of increased forest size with increased exclusion suggests that economies of scale for various forest uses outweigh diseconomies of scale in defending forest resources. The Ambiguous Role of Risk Theory and case studies suggest that high levels of ecological and economic risk inculcate risk-aversion, encourage reciprocity and redistribution in resource management, POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 21 and discourage exclusionary regulation of resources. The model provides little support for this hypothesis, although it directly addresses only the third part. Unpredictable availability of forest products and high levels of dependence upon forest resources for subsistence correspond with lower probabilities of exclusionary action. The relationships, however, are neither substantively noteworthy nor statistically significant. Ecological risk has been measured at the level of forest products rather than the forest as a whole; riskaversion may emerge only when ecological risk occurs at the level of the forest system. Although the risk associated with subsistence livelihoods yielded little predictive leverage, the dampening of economic risk associated with high levels of full-time employment proves to be significant. More research is needed to untangle the seemingly contradictory relationship between economic risk and strategies for regulating forest resources. Political Context The existence of conflict, the presence of clearly distinctive and marginal groups, and relations with external political authorities were expected to affect the probability that a user group would attempt to exclude others. The model confirms the importance of conflict and relations with external political authorities, but calls into question the significance of distinctive or marginal groups. Two measures distinguished between conflicts within and among user groups. It was suggested that conflicts within groups would lower the ability to act collectively to exclude others whereas conflicts between groups encourage efforts at exclusion to head off political challenges. The model shows that all conflicts, whether within or between groups, increase the probability of exclusionary action. User groups encompass POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 22 individuals with the same rights and responsibilities to a forest and its resources. As noted above, commonality in rights does not preclude other forms of politically relevant heterogeneity. Perhaps because the within-group measure of conflict assesses the disruptiveness as well as the existence of conflict, it yields substantively and statistically significant results while the between-group measure of conflict does not. A move from no conflict to conflict disruptive of day-to-day activities corresponds with a 0.27 increase in the likelihood of exclusionary action. Of three measures of distinctive or marginal groups, none have substantively or statistically significant relationships with the likelihood of exclusion, and only two have the predicted sign. Neither the presence of mobile groups, large differences in wealth, nor partial participation in decision-making has much bearing upon efforts to exclude others from forest resources. Indicators of the larger political context loom much larger. Government action to exclude resource users from forest resources, recognized village tenure, and ambiguity in the legal standing of harvesting forest products are all substantively and statistically noteworthy predictors of exclusionary action. Government action to exclude people from use of forest resources appears to preempt exclusionary action by groups of citizen who use those resources. The likelihood of exclusionary action by a user group decreases by 0.14 when the government adopts exclusionary policies. Village tenure over the forest, on the other hand, increases the likelihood of exclusionary action by user groups by 0.46. Substantively, this is the most important factor other than population density. Exclusionary actions become more probable (by 0.14) when use of forest products is neither legally recognized nor forbidden. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 23 Robustness and Summary of Data Analysis The key findings are robust to modifications of the model to check for biases arising from the relational structure of the database and the uneven geographic distribution of sites. The most important predictors of exclusionary action in the modified model are forest size, the presence of mobile groups, village tenure, and ambiguous legal standing of resource use. The appearance of mobile groups as statistically significant in the modified model provides some support for the expectation that marginal groups are particularly vulnerable to exclusion, but also suggests that indicators of marginality vary according to the context. Population density and distance from the forest prove not to be statistically robust predictors of exclusionary actions. Disruptive conflict remains statistically significant, but at the weaker 0.10 standard for statistical significance. The details are reported in the appendix. Political factors emerge as the most substantively important and statistically robust categories of predictors of efforts to regulate forest use through exclusion. Two of the three most robust predictors of exclusionary action by user groups are political in nature: village tenure over forested land and ambiguous legal status for current patterns of resource use. The third statistically robust predictor is the size of the forest. This relationship strongly counters expectations that the difficulty of defending larger forests discourages exclusionary efforts. Perhaps economies of scale in forest use outweighs diseconomies of scale in forest defense. The interaction of these opposing forces deserves closer attention in subsequent research. Other substantively important factors include local political conditions like disruptive conflicts and the presence of mobile groups, demand for forest products as reflected by population density, and the existence of POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 24 government policies or actions to exclude people from forests. The statistical significance of these relationships, however, depends upon the specification of the model. Political Context and Strategies for Regulating Resources Critics have repeatedly noted the prominence and limits of case studies in research on natural resource management at the local level (Agrawal forthcoming; Baland and Platteau 2000 [1996], 184; Bardhan and Dayton-Johnson 2000, 14; DaytonJohnson 2000, 20; Ostrom 1990, xiv-xv). The current project moves beyond both case studies and databases constructed by coding case studies (cf., Agrawal and Yadama 1997; Dayton-Johnson 2000). Use of the relatively large IFRI database allowed empirical assessment of five alternative hypotheses (i.e., demand and defense, risk aversion, conflicts, marginal groups, and political opportunity structure) and several alternative interpretations of each hypothesis. The analysis suggests that explanations of exclusionary tactics based on political conditions at a scale larger than the study site are more informative than explanations based on economic value, the difficulty of defending resources, assessments of risk, local conflicts, or the presence of marginal groups. Instead of dismissing the relevance of local-level factors, the model evaluates the relative influence of different aspects of each hypothesized relationship. Among indicators of resource value, land value associated with population pressure played a more important role than reliance on the forest for commercial activities. The alleviation of risk through full-time wage employment more closely corresponds with exclusion than either unpredictability of forest products or reliance on the forest for subsistence does with the absence of exclusion. Marginality in the form of mobile groups predicts exclusionary action better than either differences in wealth or arrangements for decision- POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 25 making that include only a fraction of resource users. Among measures of external political context, exclusionary action by the government yielded less predictive value than ambiguous legal standing of resource use and village tenure. These findings do not exhaust possible interpretations of the hypotheses under consideration, but do provide some sense of which local-level relationships have the strongest bearing upon exclusionary actions across country settings. My findings heighten suspicions that larger-scale context conditions local-level decisions about resource management. Decisions about tenure over forests and the legality of resource use generally get made at some level above the forest-using community or set of communities. The implications are manifold. If political factors defined at larger scales of political organization condition local strategies for resource management to such an extent, what is the best way to conduct comparative research on these questions? Many studies of natural resource management at the local level, particularly those which focus on resources held in common, attempt to analyze the relative importance of local-level variables while ignoring larger-scale political or economic conditions. The findings presented above provide some sense of the folly of ignoring macro-level dynamics. 12 Analyses that omit important variables produce unreliable results. Artifacts of larger-scale conditions may appear to be significant, while the importance of other factors may be obscured by the absence of larger-scale controls. The importance of regional or national context raises questions about the best way to research questions about strategies for resource management (Agrawal forthcoming). The concern with the inequity associated with exclusion is general, validating the search 12 A comparable argument can be made about analyses at the regional or national level that ignore dynamics at the local level POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 26 for relationships that hold across national boundaries. If strategies for resource management are contingent upon context, patterns that hold within each context would seem to be at least as interesting theoretically and practically as patterns that exist across contexts. It would be important to know, for example, whether the absence of instances of exclusion in Uganda is a product of high levels of migration and disruptions to social organization associated with that country’s turbulent political history. Political factors figure among the most important local-level predictors of exclusionary actions. The influence of conflicts upon exclusionary action underlines the inherently political nature of natural resource regulation. That redefinition of access and distribution of resources generates political struggle comes as no surprise. The relative unimportance of economic indicators raises another more controversial possibility. Redefinition of rights to resources is not merely influenced by political struggles; but seems to be motivated by political struggle (cf., Agrawal 1999, 59-60). Confirming the generality of this dynamic requires more detailed analysis of particular cases. This paper takes a first step in assessing the relative importance of a variety of political and economic factors for exclusionary strategies, but many miles lie ahead. The analysis affirms the importance of formal rights and decision-making authority. It also confirms suspicions that inequalities in wealth provide little insight into decisions about resource management (cf., Baland and Platteau 1999). Not all findings met expectations. Because larger forests are thought to be more difficult to defend, exclusionary efforts were expected to decrease with forest size. Instead, the likelihood of exclusion increased with the size of the forest. Are marginal groups at particular risk for exclusion? Are efforts at exclusion better understood as products of political conflict than efforts to lay POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 27 claim to valuable resources? The data are ambivalent on these points. And the findings presented here do not address inclusive strategies for managing resource use by regulating the distribution of a limited quantity of produce. Future research will have to determine whether the factors most important for strategies of exclusion are also the most important for more inclusive strategies. With more than two options for regulating natural resources, we cannot assume that the variables with the strongest bearing upon exclusion are also the most important predictors of each alternative to exclusion. Risk aversion could strongly influence the adoption of redistributive strategies, for instance, despite its weak relationship with exclusionary efforts. I have focused on strategies of exclusion as a starting point. The long-term goal is to understand exclusion relative to other strategies for resource management, such as exclusion of all local resource users by the government, restricted quantities distributed by various rules (e.g., equal share, by past use, by assets or need), and reductions in quantities harvested that follow various rules (e.g., equal versus proportional reductions). Exclusionary actions are not mere reflections of perceived increases in scarcity, levels of environmental or economic risk, or the degree of heterogeneity among forest users. These factors are important, but political relations among groups within a community and between resource users and outside authorities are more reliable predictors of efforts to exclude others from forest resources. Even if the most important site-level variables depends upon the strategy for regulating resources, political relations define the overarching context for all of these decisions. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 28 Table One: Logit Analysis of Efforts to Exclude Others from Forest Resources Variables Predicted Sign POPPRESS + POPPRESS2 - COMMERCE Coefficients (Standard Error) (0.0177) 2.188433 -0.0004** (0.0002) -4.349123 + -0.9148 (0.8909) -0.076721 LOSTSPECIES + -0.2546 (0.1517) 0.320285 SIZE - 0.0006* (0.0003) 0.221751 DISTANCE - -0.7659* (0.3218) -0.192695 ECORISK - -0.1534 (0.2422) -0.051464 EMPLOYED + (0.9607) 0.217247 SUBSISTENCE - (0.4978) -0.002129 CONFLICT - 1.0647*** (0.2784) 0.267881 INTERGCONFL + 0.7641 (0.4406) 0.071338 MOBILE + 1.2176 (0.7678) 0.151608 WEALTHDIF + 0.2782 (0.5154) 0.023335 PARTRULE + -0.7181 (0.6915) -0.052583 GOVEXCLU - -1.9295*** (0.6151) -0.143671 COMMUNITY + 2.8477*** (0.6567) 0.462273 AMBIGLAW + 1.3052*** (0.4059) 0.142173 Constant N = 353 Log-likelihood = -119.31498 Pseudo R 2 = 0.4329 0.0750*** Effect of a Change from Min. to Max., Other Variables at Mean 2.5905** -0.0254 -3.6068 (0.9426) chi-squared = 182.17 Prob > chi-squared = 0.0000 Notes: Data source: International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) database. Six failures and 0 successes were completely determined. Italicized variable names highlight relationships that run contrary to prediction. * ** *** P < 0.05 P < 0.01 P < 0.005 POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 29 Appendix: Robustness of Results Many-to-many relationships exist among user groups, forest products, and forests in IFRI’s relational database. As a result, user groups and forests often appear more than the once in the data, with the number of repeat appearances depending upon the number of forests each user group uses and the number of forest products obtained from each forest by each user group. In some sites, a single user group uses one or two forest products from a single forest. Elsewhere, each user group may use two or more forests for several different products. Sites with complex relationships among user groups, products, and forests will be represented more frequently in the analysis than sites with fewer entities and fewer relationships among entities. If independent variables are also correlated with the complexity of the sites, the results may be misleading. The nature of the IFRI research network presents additional sources of potential bias. The IFRI network was launched with three collaborating research centers in 1993 and has grown over time. The database currently stores data collected in twelve countries: Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Kenya, Mexico, Nepal, Uganda, the USA, and Tanzania. 13 The oldest centers account for a disproportionately large number of the cases. Of 141 sites in the database, 25.5% are in Uganda, another 25.5% in Nepal, and 16.3% in the USA. 14 Disproportional representation of countries is even higher for some entities and relationships. Nepal, for example, accounts for 44.2% of the user group - forest product – forest relationships that serve as cases for my analysis. If overarching political conditions affect the likelihood of efforts to exclude others from use 13 There are thirteen centers in the IFRI network, but not all centers have existed long enough for their data to be entered into the common database. 14 If distributed uniformly across countries, 8.3% of the sites would be located in each country. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 30 of forest resources, the uneven distribution of sites across countries with diverse political systems and histories can be expected to affect the results. The USA is not overrepresented with 6.8% of the cases. Political and economic conditions distinguish the USA from the other countries to such an extent, however, that it could be conceived as a different type altogether. Uganda, where no efforts at exclusion by user groups were recorded, presents a potential source of bias as well. Although Uganda is not unique in having no mentions of exclusionary action for any of its sites, it accounts for a far larger proportion of the data (16.1%) than any other such country. To check for sensitivity to the location of sites, cases from Uganda were dropped and dummy variables for Nepal and the USA were added to the model. Calculation of robust standard errors corrects for clustering on a particular variable, and thus accounts for bias emerging from the relational nature of the database. The modified model has been calculated with standard methods and with standard errors corrected for clustering on user groups; both sets of standard errors appear in Table Two. [Insert Table Two about here] The main conclusion, that political factors are the most important predictors of exclusionary action, is not simply an artifact of the database structure or sampling. The most important predictors of exclusionary action in the modified model are forest size, the presence of mobile groups, village tenure, and ambiguous legal standing of resource use. Population density, distance from the forest, and disruptive conflict fail to meet the 0.05 threshold of statistical threshold after corrections have been made for clustering on user group, although disruptive conflict remains statistically significant at the weaker 0.10 standard. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 31 The emergence of mobile groups as statistically significant predictors of exclusionary action represents the most important finding in Table Two. If exclusionary action is more likely to target distinctive and marginal groups, mobile groups should be particularly vulnerable. The original model, however, provided little support for either the general expectation that the presence of marginal groups increases the likelihood of exclusion or the specific expectation about the vulnerability of mobile groups. The presence of mobile groups increased the likelihood of exclusion by 0.15, but this relationship lacked statistical significance. Only with the exclusion of data from Uganda and the inclusion of dummy variables for Nepal and the USA does the presence of mobile groups take on a statistically as well as substantively significant role. The statistical significance of the relationship survives the correction for clustering on user group. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 32 Table Two: Logit Analysis of Efforts to Exclude Others from Forest Resources Checking for Autocorrelation with Nepal or the USA Dropping Cases from Uganda Adjusting Standard Errors for Clustering on User Group Variables POPPRESS Coefficients 0.0596 POPPRESS2 -0.0003 0.0002 (0.0002) COMMERCE -0.6222 0.9820 (2.1531) LOSTSPECIES -0.1848 0.1678 (0.0009) 0.0005*** (0.0009)* SIZE 0.0022 Standard Errors 0.0193*** (Robust Standard Error) (0.0391) DISTANCE -0.6832 0.3320* (0.7267) ECORISK -0.1421 0.2710 (0.2024) 2.2791 1.7648 (3.0991) -0.3646 0.6182 (1.3220) EMPLOYED SUBSISTENCE CONFLICT 0.9662 0.2818*** (0.5576) INTERGCONFL 0.0650 0.5287 (1.1827) MOBILE 3.0739 1.0699*** (1.3320)* WEALTHDIF 0.2259 0.5599 (1.4390) PARTRULE -0.6172 0.7088 (1.4611) GOVEXCLU -1.7928 0.6710** (1.5348) COMMUNITY 4.4522 1.0681*** (2.1608)* AMBIGLAW 1.6888 0.4696*** (0.8390)* NEPAL 2.3129 1.0215* (2.2381) USA 1.3882 1.4536 (3.3913) 1.3953*** (2.4480)* Constant -5.2039 POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 33 N = 296 For Standard Logit Model LR chi-squared = 162.06 Log-likelihood = -108.2871 Pseudo R 2 = 0.4280 Prob > chi-squared = 0.0000 For Logit Model with Robust Standard Errors Wald chi-squared = 39.56 Prob > chi-squared = 0.0037 Notes: Data source: International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) database. Six failures and 0 successes were completely determined. Location of a site in Uganda perfectly predicts the absence of exclusionary action. To check sensitivity of results, 57 cases from Uganda are dropped from the above analysis. * ** *** P < 0.05 P < 0.01 P < 0.005 POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 34 Works Cited Agrawal, Arun. Forthcoming. “Common Property Institutions and Sustainable Governance of Resources,” World Development. Agrawal, Arun and Sanjeev Goyal. 2001. “Group Size and Collective Action: Third Party Monitoring in Common-Pool Resources,” Comparative Political Studies 34, no. 1: 63 – 93. Agrawal, Arun. 1999. Greener Pastures: Politics, Markets and Community among a Pastoral Migrant People. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Agrawal, Arun and Gautam N. Yadama. 1997. “How do Local Institutions Mediate Market and Population Pressures on Resources? Forest Panchayats in Kumaon, India” Development and Change, 28, no. 3 (July): 435 – 465. Alchian, Armen and Harold Demsetz. 1973. “The Property Rights Paradigm,” Journal of Economic History, 33 (1): 16-27. Anderson, Terry L. and P.J. Hill. 1977. "From Free Grass to Fences: Transforming the Commons of the American West," in Garrett Hardin and John Baden, editors, Managing the Commons. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. Baland, Jean-Marie and Jean-Philippe Platteau. 2000 [1996]. Halting Degradation of Natural Resources: Is There a Role for Rural Communities? New York: Oxford University Press. Baland, Jean-Marie and Jean-Philippe Platteau. 1999. “The Ambiguous Impact of Inequality on Local Resource Management,” World Development 27, no. 5: 773 – 788. Baland, Jean-Marie and Jean-Philippe Platteau. 1998. “Division of the Commons: A Partial Assessment of the New Institutional Economics of Land Rights,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 80 (August): 644 – 650. Bardhan, Pranab and Jeff Dayton–Johnson. 2000. “Heterogeneity and Commons Management.” Paper prepared for the National Research Council’s Institutions for Managing the Commons project. Baumol, William, J. Panzar, and Robert Willig. 1982. Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure. New York. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Cited in John Quiggin. 1993. “Common Property, Equality, and Development,” World Development 21, no. 7: 1123 – 1138. Behnke, R. H. and Ian Scoones. 1993. “Rethinking Range Ecology: Implications for Rangeland Management in Africa,” in R. H. Behnke, Ian Scoones, and C. Kerven, POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 35 eds., Range Ecology at Disequilibrium: New Models of Natural Variability and Pastoral Adaptation in African Savannas. Berry, Sara. 1993. No Condition is Permanent: The Social Dynamics of Agrarian Change in Sub-Saharan Africa. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. Bruce, John W. and Shem E. Migot-Adholla, eds. 1994. Searching for Land Tenure Security in Africa. A World Bank book. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dayton-Johnson, Jeff. 2000. “Choosing Rules to Govern the Commons: A Model with Evidence from Mexico,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 42: 19 – 41. Dyson-Hudwon, Neville. 1985. “Pastoral Production Systems and Livestock Development Projects: An East African Perspective,” pages 157 – 186 in Michael Cernea, ed., Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural Development. New York: Oxford University Press. Ensminger, Jean. 1992. Making A Market: The Institutional Transformation of an African Society. The Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Fearon, James D. and David D. Laitin. 1996. “Explaining Interethnic Cooperation,” American Political Science Review, 90, no. 4 (Dec): 715 – 735. Ghate, Rucha. 2000. “The Role of Autonomy in Self-Organizing Processes: A Case Study of Local Forest Management in India.” Working Paper W00-12. Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. Gibson, Clark C. and Tomas Koontz. 1998. “When ‘Community’ is Not Enough: Institutions and Values in Community-Based Forest Management in Southern Indiana,” Human Ecology 26, no. 4: 621 – 647. Hardin, Garrett. 1968. “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162: 1243 - 1248. Hyden, Goran. 1983. No Shortcuts to Progress: African Development Management in Perspective. London: Heinemann Educational Books, Ltd. McKean, Margaret A. 1992. “Management of Traditional Common Lands (Iriaichi) in Japan,” pages 63 - 98 in Bromley, Daniel W. et al., eds. Making the Commons Work: Theory, Practice, and Policy. San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 36 Netting, Robert McC. 1981. Balancing on an Alp: Ecological Change and Continuity in a Swiss Mountain Community. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. North, Douglass C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. North, Douglass. 1981. Structure and Change in Economic History New York: Norton. Norberg, Kathryn. 1988. “Dividing Up the Commons: Institutional Change in Rural France, 1789 - 1799,” Past and Present, Vol. 16, No. 2-3: 265-286. Olson, Mancur. 1965. The Logic of Collection Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Ordeshook, Peter. 1986. Game Theory and Political Theory: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press. Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Ostrom, Elinor, Roy Gardner, and James Walker. 1994. Rules, Games, and CommonPool Resources. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. Ostrom, Elinor. 1999. Self-Governance and Forest Resources. CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 20. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Peters, Pauline E. 1994. Dividing the Commons: Politics, Policy, and Culture in Botswana. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia. Quiggin, John. 1993. “Common Property, Equality, and Development,” World Development 21, no. 7: 1123 – 1138. Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Ruttan, Lore. 2001. “The Ecology of Cooperation: Information Sharing Among Commercial Fishers.” Unpublished paper prepared for Spring Mini-Conference, Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. Schlager, Edella, William Blomquist and Shui Yan Tang. 1994. “Mobile Flows, Storage and Self-Organized Institutions for Governing Common-Pool Resources,” Land Economics 70, no. 3 (August): 294 – 317. POTEETE – Exclusion in forest management 37 Scott, James C. 1976. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press. Segosebe, Eagilwe M. 1997. Pastoral Management in Botswana: A Comparative Study of Private and Communal Grazing Management in the Kweneng and Southern District. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation (Geography). Worcester, MA: Clark University. Western, D. 1982. “The Environment and Ecology of Pastoralism in Arid Savannas,” Development and Change 13: 183 – 211.