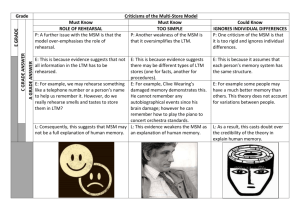

MSM and the Efficient Market Hypothesis: An Empirical Assessment

advertisement