Marketing Theory A history of schools of marketing thought

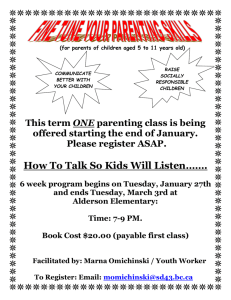

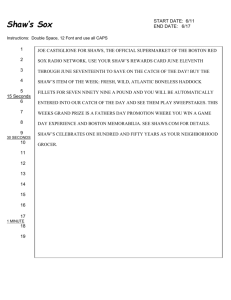

advertisement