The Evolution of the Various Theories on the... Motivation

advertisement

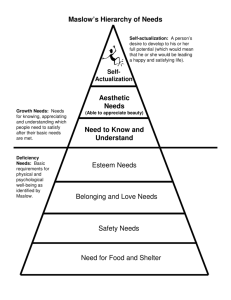

The Evolution of the Various Theories Motivation on the subject of A Paper presented to the MBA Class, Lansdowne Independent College, London, June 1988. Yusuf A. Nzibo Introduction Motivation at work is an important area of study that has over the century continued to fascinate students of Organisational Behaviour. Behavioural scientists have made enormous contributions to our understanding of individual motivation, group behaviour, and interpersonal relationships at work, and this has enabled managers to become much more sensitive and sophisticated in dealing with their workers. Motivation remains an important area of concern for managers and for all those involved in seeking to improve the productive element of people in organisations. J. N. Harris and R. Woodgate define motivation as "the processes or factors causing people to act in certain ways ... consists of the identification of need, the establishment of a goal which will satisfy that need and determination of the required action".1 However, students of motivation have not come to a general agreement as to a uniform definition of motivation and not all of them base their theories on needs. To help us out of this dilemma, T. R. Mitchell suggests four common characteristics that can help define motivation. These are: Motivation is typified as an individual phenomenon, to allow for individual differences and unique ness; Motivation is described, usually, as intentional, i.e. under a person's control; Motivation is multifaceted, with the two most important facets being what gets people activated (arousal) and the force to engage in desired behaviour (direction or choice), and The purpose of motivational theories is to predict behaviour i.e. it is concerned not with behaviour or performance themselves but with action and with the forces that influence the choice of action.2 Michael Argyle pointed out in 1972 that: The problem of motivation has become particularly acute now that many young people feel no great economic need to work, and are not endowed with the motive to achieve, which was particularly responsible for the industrial expansion in previous periods of history. 3 It is the argument of this paper that the various theories developed by social scientists concerning the subject have tended to be influenced by the then general climate of opinion about man and his relation to work. In the early days of industrialisation when conditions were harsh, man was seen as a passive animal to be manipulated, motivated through wages, and controlled for his own “good". The great depression and the war experiences, and government intervention into the running of welfare states, led to change of attitude and the rise of human concern. Thus man began to be seen as a social man whose problems could no longer be treated in isolation. The 1960s brought new changes in which money was no longer seen as a primary motivator as the “quality of life issues" began to dominate. Man was thus seen as self-actualising and motivated by a number of complex factors. The study of motivation had thus to be studied from an inter-disciplinary approach. Tools were thus borrowed from all possible disciplines of the social sciences. Thus it is this under standing of man from a wider perspective that has enriched the study of the motivation theories. THE EVOLUTION OF MOTIVATIONAL THEORIES The Scientific Management School of Thought This school of thought propounded by scholars such as Frederick Winslow Taylor 1856-1915), Henry L. Gantt and Frank and Lillian Gilbreth were partly concerned with the need to increase productivity at a time when there was a shortage of skilled labour at the beginning of this century. Taylor developed theories of work organisation that were meant to improve the effectiveness of workers and thus raise their productivity. Some of his ideas were thus to crystallise into a theory of industrial motivation which was considered radical at that time.4 The ideas of Taylor and the others were based on the then popular model of human behaviour that saw people as "rational beings" motivated primarily by a desire for material gain. It was thus assumed that workers would therefore act in a manner best suited to satisfy their economic and physical needs. The theories thus epitomised the Protestant ethics of master-servant relationship in which both parties were for the most part economically motivated, competitive and self interested.5 These theories were based on the assumptions (later to be found wanting) that: people only try to satisfy economic needs at work; the sole reward they seek is money; people's behaviour is always rational in pursuit of that goal; they always try to maximise their rewards in return for an instrumental and calculated amount of effort; emotional needs do not enter the picture; and that the interests of the worker and employer are mutual and as such no conflicts exist. Taylor and the other theorists focused their efforts on finding ways of improving workers' physical capabilities believing that workers were 2 motivated by high wages and salaries and the chance of improving their lives. These two things, it was argued if they were properly taken care of, workers would work continuously and effectively in a mechanically pre-described manner, and thus production would be improved. The theorists, however, overlooked the human desire for job satisfaction and social needs of workers as members of groups that they worked in. They also failed to consider the tension created when needs was frustrated. They took too much granted believing that workers Could be motivated by being offered better pay and being trained in more efficient ways of completing their tasks, and since they saw the problem from the perspective of increasing productivity, workers' social needs and inputs were totally ignored. While we all admit that financial gain is important to workers, managers have learnt through painful experience that this is not the whole story. As people went on strike over their working conditions in the post-War I period, and many found their jobs unfulfilling new solutions had to be found, and the whole issue of motivation had to be addressed afresh. The Human Relations School of Thought The "simplistic" view of motivation came under heavy criticism from a new school of thought known as “The Human Relations School of Thought “. Men like Elton Mayo6 argued that workers have other than purely economic motives, and that there are many Incentives of which under normal conditions, money is the list important. They argued that the "carrot-and-stick" hypothesis about the relationship between behaviour and reward was of doubtful validity. That the hypothesis of the previous school of thought depended very much on a view of the worker as an isolated individual rather than a social being engaged in, and deriving satisfaction from, his reactions with his fellow beings. Thus new factors had to be found to explain motivation. The new views centred on a view of the Social Man seeking satisfaction primarily by membership of stable work-groups. The Hawthorne Experiments Elton Mayo revealed some important consideration almost by accident. Together with a group of fellow researchers investigating industrial efficiency, he conducted a series of experiments at the Hawthorne plant of the Western Electric Company near Chicago in the United States. The famous "Hawthorne" experiments – written by Roethlisberger and Dickson (1939) – became an important landmark in the development of behavioural theory. They conducted their experiments in two phases: 1924-27 they investigated the effects of changes in illumination on productivity and showed that there were certain factors, apart from physical ones, which affected the motivation and productivity of a group of workers. Their investigations from 1927-1932 consisted of four main 3 experiments in relay assembly and mica-splitting test-rooms and in the bank wiring observation room.7 The study in the relay assembly test-room involved five girls and took two years and involved various changes in the working conditions, style of supervision and pay incentives. The outcome was that productivity was higher than in controlled groups, there was greater group cohesion, better communication and working relationships. The result of this study led to the "Hawthorne effect" theory that argued that any group singled out as an object of interest acquires ego-satisfaction which could have a positive effect on production. In the other experiments involving men, considerable social pressure was applied in the form of various verbal censures was placed informally by the group on members to conform to an accepted level of output. Out of the confusion surrounding these studies a number of conclusions were reached. Mayo held that motivation and productivity were as a result of complex behaviour patterns, and could be influenced by numerous factors. Mayo, influenced by the post-Depression and World War II philosophies that emphasised the human element, argued that Scientific Management as propounded by Taylor had paid insufficient attention to the human factor in productivity. He held that the economic motive that was so much stressed was unimportant as compared with emotional and non-logical attitudes. Mayo thus came to the following conclusion: work is a group activity; the need for recognition, security and sense of belonging was more important in determining a worker's moral and productivity than the physical conditions which he works; his attitudes and effectiveness are conditioned by social demands from both inside and outside his work place; informal groups within the factory exercise strong social control over the work habits and attitudes of an individual worker; and group collaboration must be planned and developed to reach group cohesion in order to improve productivity. Though Mayo’s works came under heavy criticism, his ideas added a rider to the previous simplistic views of the pre-War I period. Thus people became aware that in order to motivate people, one must know the incentives that people will respond to, the work environment must be improved, and that opportunities must be provided to fulfil workers' needs. The Human Relations techniques were criticised for not always producing the desired effect especially on the techniques of supervision, for lack of concern with extra-organisational factors and for ignoring environmental factors, for adopting the belief that no conflict of interest existed between workers and employers, and for under estimating the "measure of genuine conflict between the satisfaction of individual needs and the satisfaction of the organisation's goals of "efficiency".8 They were 4 accused of looking for easier answers in the form of techniques instead of questioning the organisational structure which may have been at the root of the problem. Psychologists committed to the multi-dimensionality of the human personality need, criticise them for being so obsessed with a Durkheimian emphasis on an individual's need which may be equally or more important in structuring motivation. The Post-Hawthorne Period: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs In the post-Hawthorne period students of motivation carried the subject much further, Abraham Maslow taking the lead. Psychologists and others argued that individuals should be seen as having "personality needs" and/or "generalised motives. Maslow held that man should be seen as a "perpetually wanting animal" motivated by the desire to satisfy certain specific needs which can be arranged in a hierarchical order. Theorists argued that needs and motives exert a direct influence upon behaviour; that there is a basic conflict between the needs of individuals and the goals of organisations; that this is resolved by changing the organisational structure and not by the Human Relations techniques; and that the best form of organisation is that which makes use of the potential of its workers and involves them in decision making, encourages team-work, good communication and expressive supervision. Maslow arguing that nearly all individuals are motivated by the desire to satisfy certain specific needs, classified them into five basic groups in an hierarchical order (from lower to higher): 1. Physiological – these are the basic needs such as food and water which are essential for survival; 2. Safety -- for a general ordered existence in a relatively stable, threat- free environment; 3. Love -- the needs of affectionate relations with others, a sense of belonging and acceptance as a member of a group. 4. Esteem -- a need or desire for a stable, firmly based high evaluation of us, for self respect or self-esteem. This is the desire for prestige, importance and attention, etc. 5. Self-actualisation -- the need for self fulfilment and to be able to realise one's full potential.9 Maslow argued that the behaviour of a person is dominated by the lower group of needs remaining unsatisfied. That one group must first be satisfied before one move to another set, and when they have been satisfied they cease to play an activating role. For him, “a satisfied need is not a motivator". Maslow, point Blackler and Williams, is important "because he directs attention to the point that motives may direct behaviour, and that people may engage in activities simply because they believe they are valuable and not because of other intrinsic motives".10 5 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs was however tested by Wahba and Bridwell 11 who found that they did not exist in the workplace. The main problem with Maslow's theory was that it took for granted that all human beings were homogeneous in their behaviour, and failed to take into account the impact different cultures, environment and education have on people. People in general do not have similar aspirations, even those within the same environment. Maslow's works main fault was the lack of empirical data to back his assumptions. The "ERG Theory" Clayton P. Alderfer12 made an attempt to improve on this last weakness by backing his theory in 1972 with hard data. He suggested that Maslow hierarchy of needs be reduced down to three which he termed Existence, Relatedness, and Growth. His approach was thus termed the "ERG Theory". Existence needs included all forms of physiological and material desires, and these included Maslow’s first two levels and also included money. Relatedness needs included relationship with others, and Growth needs which like Maslow's were concerned with the desire to be creative and to achieve full potential in the existing environment. He, however, rejected the concept of hierarchy and saw them as a continuum, accepted that two needs could operate contemporaneously, and took account of the environment. He suggested that extra reward at the lower levels of needs could compensate for a lack of satisfaction at higher levels. More pay could therefore make up for a lack of job satisfaction. Three American psychologists, Douglas McGregor, Rensis Likert and Chris Argyris improved on the work of Maslow in an effort to bring the insights of psychology in the study of the subject.13 McGregor rejected previous views on the attitude of workers which he termed "Theory X" that held: the average human being has an inherent dislike for work and will avoid it if he can; because of this human characteristic of dislike of work, most people must be coerced, controlled, directed, threatened with punishment to get them to put forth adequate effort toward the achievement of organisational objective; and that the average human being prefers to be directed, wishes to avoid responsibility, and has relatively little ambition, and wants security above all. He favoured the integration of the individual and organisational goals based on the assumptions he labelled as "Theory Y". This theory held that: There is no inherent dislike of work itself; man will exercise self-direction and self control in the services of objectives to which he is committed; the degree of commitment is a function of the rewards seen to result from meeting these objectives. In this context the most Significant rewards are the satisfaction of higher order of needs. Such rewards are intrinsic to work, and not externally mediated; if the conditions are right the individual will not only accept but seek 6 responsibility; a high proportion of the population is capable of imagination, ingenuity and creativity in solving organisational problems; and industrialisation has meant that such capacities are underutilised.14 He held that management method of organisation and control are the once that need improvement, and that the task of management is to arrange organisational conditions and methods of operation so that people can achieve their own goals best by directing their own efforts toward organisational objectives. Likert (1961) on the other hand, argues that managers who are prepared to take account of the "major motivational forces" that govern behaviour, can assure "attitudes of identification with the organisation and its objectives and a high sense of involvement in achieving them". He holds that where this is done, both satisfaction and productivity will increase together.15 Frederick Herzberg sort to clarify the relative importance of money vis-àvis other factors and after various investigations with his colleague he developed his famous "Hygiene Theory” that concluded that human beings have two basic Needs: the need to avoid pain and survive, and the need to grow, develop, and learn. Thus the analysis of employee job satisfaction would result in the formation of two separate continuums rather than the traditional one of satisfaction/dissatisfaction. The first set of needs, which he calls “the hygiene factors", range from dissatisfaction to no dissatisfaction are affected by environmental factors over which employees have limited influence. These include pay, interpersonal relations, supervision, company policy and administration, working conditions, status and security. These, he holds, do not serve to promote job satisfaction but their absence Create dissatisfaction. The second group of factors which he terms "motivators" concern with the work rather than with its surrounding physical, administrative or social environment. This includes achievement, the possibility of growth through self-development, and responsibility leading to advancement, etc. Thus he holds that if workers are to be motivated, their jobs are the source of that motivation.16 R. H. House and L. A. Wigdor.17 and R. Heller18 criticise Hertzberg’s two factors ideas as being a too simplistic theory of motivation, and that it ignores cognitive and co-native or effective differences as between individuals. Heller also states that it is difficult to know about men's motives as they change rapidly and people don't often admit their true motives openly. Others also accuse him of not seeing money as an important motivating factor. Despite of the criticism levelled, writers acknowledge his contribution to the issue of job satisfaction and enrichment, and his stimulation of further debate on the topic of motivation. 7 The Expectancy Theory Dissatisfaction with the motivation theories continued in the 1960s as many of the theories failed to take into account their applicability in different situations and under different cultural conditions. What was required were theories that would allow not only for this but also for the complexity and variability of man and his work set-up. The traditional views of Maslow, McGregor and Herzberg were thus found inadequate. Researchers in the last two decades have used complex models and in particular the expectancy theory to increase our knowledge on the subject. The foundation of this theory were laid by Kurt Lewin in the early 1950s and were developed a decade later by Victor Vroon19 and refined in particular by E. Lawler20 Expectancy is defined as a belief concerning the likelihood that a particular act would be followed by a particular outcome. The individual is seen as a being with beliefs and expectations about future events in his life, and this includes expectations about the outcomes of their own behaviour and preferences for particular possible outcomes. Roger Bennett points out that "our expectations about how much effort to put into a job, the likely rewards, the goals that will achieve such rewards, how we will achieve those goals, and the fairness or equity of the rewards, are important ingredients of 21 motivation". As the theory is all encompassing, it has become one of the most influential theories on motivation among the academics. Despite a need for conceptualisation and methodological refinement, the expectancy theory has much to offer, especially in the area of individual rewards. Conclusion While the subject of motivation has attracted a lot of academic debate, and its development and refinement continues, the last eight decades has allowed us a sufficient grasp of the subject as to be able to apply the knowledge in the efficient running of organisations. However, as our ideas of man and his work change and we continue to encounter more complex technological problems, so too will our curiosity in understanding "What Really Motivates MAN?" What we have learnt so far is that money is not the only thing that motivates a man and that it can even be secondary; the work environment, the job design, the style of supervision, non-material incentives, all count in motivating workers. The 1960s also taught us that people partly work because of intrinsic satisfaction, and Herzberg, Mc Clelland and Maslow drew our attention to other needs such as the desire for achievement and recognition, and the need of job enrichment. We have also learnt that achievement motivation can be aroused by job challenges and target setting, and finally that workers become committed to an organisation's goals through such 8 things as allowing them to take part in decision making especially concerning the nature of their jobs and team work. Footnotes: 1. J. N. Harris & R. Woodgate, Making Sense of Management Jargon, Granary Press, 1984. 2. T.R. Mitchell, “Motivation--New Directions for Research, Theory and Practice,” Academy of Management Review, 7, No. 1, January 1982, pp. 8-88. 3. M. Arggyle, The Psychology of Work, Penguin, 1972. 4. See F.W. Taylor, Scientific Management, Harper & Row, 1947. 5. M. H. Bottomley, Personnel Management, Pitman, 1987, p. 14. 6. See E. Mayo, The Human Problems of the Industrial Society, Harvard University Press, 1945. 7. See E. Mayo, "Hawthorne and the Western Electric Company" in D.S. Pung, Organization Theory: Selected Readings, Penguin, 1984, pp. 279-292. 8. D. Silverman, The Theories of Organizations, Gower, 1984, p.76. 9. See A.H. Maslow, "A Theory of Human Motivation", Psychological Review, 50, 1943, pp.370-96, and A.G. Cowling et al. Behavioural Sciences for Managers, Edward Arnold, 1988, pp. 68-70. 10. See F.H.M. Blackler & A.R.T. Williams, "People's Motivation at Work", in P. Warr, Psychology at Work, Penguin, 1971. 11. See M.A. Wahba & L. G. Bridwell, "Maslow Reconsidered", in Organisation Behaviour and Industrial Psychology, O.U.P., 1975. 12. C.P. Alderfer, "An Empirical Test of A Theory of Human Needs", Organisational Behaviour And Human Performance, 4, 1969, pp. 142-175. 13. See D. McGregor, The Human Side of Enterprise, McGraw-Hill, 1960; R. Likert, New Patterns of Management , McGraw-Hill, 1961; and Chris Argyris, Integrating The Individual And Organisation, Wiley, 1964. 9 14. For details see D.S. 317-333. Pung, Organization Theory, Pelican, 1984, pp. 15. D. Silverman, Op. cit., p. 73. 16 F. Herzberg, Work and the Nature of Man, World Publishing Co., 1966, pp. 71-91. 17. See R. H. House & L.A. Wigdor, "Herzberg's Dual-Factor Theory of Job Satisfaction and Motivation: A Review of the Evidence and Criticism", Personnel Psychology, 20, 1967. 18. See R. Heller, The Naked Manager, Barrie & Jenkins, 1972. 19. V. Vroon, Work and Motivation, London, Wiley, 1964. 20. See for example E.E. Lawley, "Job Attitudes and Employee Motivation: Theory, Research and Practice", Personnel Psychology, 23, 1970. 21. R.D Bennett, "Motivation at Work" in A.G. Cowling, et al., Op. cit., p.80. 10