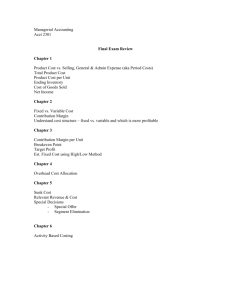

CSUN GATEWAY Managerial Accounting Study Guide

advertisement