The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

advertisement

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

Nominal and Real Union Wage Differentials and the Effects of Industry and SMSA Density:

1973-83

Author(s): Barry T. Hirsch and John L. Neufeld

Reviewed work(s):

Source: The Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Winter, 1987), pp. 138-148

Published by: University of Wisconsin Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/145872 .

Accessed: 19/04/2012 18:30

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Wisconsin Press and The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System are

collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Human Resources.

http://www.jstor.org

Nominal and Real Union Wage Differentials and

the Effects of Industry and SMSA Density:

1973-83

I. Introduction

Estimation of union-nonunion relative wage differentials has

for some time received considerable attention from labor economists. Lewis

(1986) has recently surveyed about 200 empirical studies providing empirical analysis of data through 1979. In this paper, we provide estimates of

nominal and real union-nonunion wage differentials for the period 1973-83,

based on separate samples of male production workers in manufacturing,

production workers in nonmanufacturing, and nonproduction workers

economy wide.

The purpose of this study is threefold. First, systematic comparison of

nominal versus real wage differentials allows us to evaluate Lewis's conclusion, based on a limited number of studies, that there is no significant

difference between these measures. Second, we are able to provide estimates of the union-nonunion differential over an eleven year period, including several sample years since Lewis ended his survey. Finally, we provide

estimates of the effects of both industry and SMSA density on the union

differential and the wages of union and nonunion workers.

II. Estimation and Data

In order to obtain estimates of the union-nonunion wage

differential, micro log wage functions are specified for union and nonunion

workers. Letting i index individual workers, k a worker's 3-digit industry, m

a worker's SMSA, and superscripts u and n union and nonunion status,

respectively, the following equations are estimated by OLS:

(1)

ln(w)' = Ox"+ SEIP"X + UPik + 8UPim+ e'

(2)

ln(w)i = an + SX?

+ ^"P + 8p

+e

where w is the wage, X is a vector of earnings-related individual characterisThe authorsacknowledgethe helpfulcommentsof two anonymousreferees.

[SubmittedAugust 1985;acceptedJuly 1986]

THE JOURNAL

OF HUMAN

RESOURCES

? XXII

* 1

Communications

tics, P is union density, and e" and en are error terms assumed to be

uncorrelated with zero means and constant variances.'

The logarithmic union-nonunion wage differential (or wage gap), d, is

calculated by:

(3)

d = (ou -

") +

(

-

n)+

(U

- yn)Pk

+ (u

-

)Pm.

where the means of X, Pk, and Pm are all-worker means (hence, d is a

weighted average of log differentials calculated using union and nonunion

means). The percentage differential, D, is most easily approximated by:

(4) D = [exp(d) - 1]100.

More precise estimation methods are provided in Kennedy (1981) and Giles

(1982). Below, all results are presented as log differentials.

The primary data used in this study come from the May 1973-81 and 1983

Current Population Survey (CPS) tapes. All employed nonfarm nonschool

males between the ages of 18 and 64 residing in 29 of the largest 30 SMSAs

are included.2 Union density, defined here as the percentage of eligible

workers who are union members, is available for three-digit Census industries and SMSAs in Kokkelenberg and Sockell (1985).3 In order to obtain

real wage estimates, nominal wages (usual weekly earnings divided by usual

hours worked per week) are deflated by BLS intermediate budget figures

once provided annually for large SMSAs (Census Bureau).4 The vector X

includes years of schooling, experience (age - schooling - 5), experience

1. As is well known, OLS is not without problems. Receiving the most attention in the

literature has been the potential bias resulting because of the simultaneous determination of

union status and wages and, relatedly, selectivity bias resulting from unobserved differences

between union and nonunion workers with identical measured characteristics. Lewis (1986)

provides an analysis of methods intended to address these problems (e.g., inclusion of a

selectivity variable in the wage equations and the use of fixed-effects models with panel data).

Because alternative methods also introduce potentially serious problems, OLS is used here.

This helps avoid entangling the effects of cost-of-living or union density adjustments with those

from use of alternative estimation procedures.

2. There was no public use 1982 survey. Sample sizes are reduced after 1978 because all

rotations were not asked their usual weekly earnings. CPS coding of the SMSAs is based on

1970 Census population counts. Miami is excluded due to insufficient cost-of-living data.

3. Kokkelenberg and Sockell (1985) provide union data based on the 1973-81 May CPS (the

CPS union question did change during this period; see Footnote 6). Density data for SMSAs are

provided yearly while for industries, data are presented as three-year moving averages. Hence

our 1973 and 1974 regressions include industry density for 1973-75, regressions for 1980 on

include the 1979-81 industry density measures, and the 1983 regressions include the 1981

SMSA density measure. Measurement error associated with this imperfect matching is probably minor given the year-to-year stability in relative interindustry and interarea unionization.

4. Such figures are no longer provided by BLS. Our 1983 budget figures were generated by

inflating prior year budget figures by SMSA-specific consumer price indices (U.S. Bureau of the

Census).

139

140 The Journalof Human Resources

squared, and dummies for race, marital status, veteran status, region,

samples).

1-digitoccupation,and 1-digitindustry(in the nonmanufacturing

III. Nominal versus Real Wage Differentials

by Year

As noted by Lewis(1986, 105), the use of nominalratherthan

real wage rates might lead to an upwardbias in wage gap estimatessince

unionworkersare more likelyto residein highercost-of-livingareas.Based

on unpublishedresultsextractedfrom four studies, however, Lewis tentativelyconcludesthat adjustmentsfor cost of livinghave little effect on wage

differentialestimates.We firstexaminethe potentialfor bias in unionwage

differentialestimatesby comparingdifferencesbetween nominaland real

wage rates for union and nonunionworkersover the 1973-83 period. As

hypothesizedby Lewis, we find a potentialfor bias. Adjustingfor cost-oflivingdifferencesreducesunionwagesby an average1.15percentrelativeto

nonunionwages.

Table 1 presentsestimates of union-nonunionlog wage differentialsby

yearfor the threesubsamplesof maleworkers.As foundin previousstudies,

the union wage effect for productionworkersis smallerin manufacturing

than in nonmanufacturing,while estimatedunionwage effects for nonproduction workersare close to zero (see Antos 1983).

The average (unweighted)differencebetween the nominaland real differential over the 1973-83 period, d(nom) - d(real), is presentedin the

next to last row of Table 1. Among productionworkersin manufacturing

(the most frequentlystudiedgroupin the empiricalliterature),nominaland

real differentialsare virtuallyidentical, the averagedifferencebeing less

than a tenth of a percent. However, amongproductionworkersoutside of

manufacturing,estimates of nominaldifferentialsare about 1 percentage

point higherthan estimatesof real differentials.While a 1 percentagepoint

bias is not trivial,it is less thanthe bias attributedto the exclusionof fringe

benefits (Freeman 1981), work conditions (Duncan and Stafford 1980),

union dues (Raisian 1983), selectivity,and other factors(for a survey, see

Lewis 1986). Among nonproductionworkers, no evidence is found of a

union-nonunionwage differential;hence, values of d(nom) - d(real) for

this grouphaveless meaning.The bottomline of Table 1 presentsd(nom) d(real) calculatedfrom regressionsexcludingthe regionalvariables,which

to some extent proxycost-of-livingdifferences.Even with the exclusionof

these controlvariables,differencesbetween nominaland real union wage

gaps are small on average (complete results are availableon request).

On the basisof the resultspresentedin Table 1, it appearsfairto conclude

that no significantportionof the union-nonuniondifferentialconstitutesa

Communications

compensating differential for higher living costs. It likewise follows that no

significant bias has been introduced in previous studies by ignoring cost-ofliving differences. For most research efforts in this area, the benefits from

considering cost-of-living differences are likely to be less than the costs of

limiting one's sample to large SMSAs (plus the costs from introducing

additional measurement error associated with the cost-of-living indices).5

Indeed, it should be noted that union wage gaps estimated for workers in

SMSAs are lower than corresponding economy-wide wage gaps (Lewis

1986, 134-36).

Our results also provide evidence on changes over time in the unionnonunion wage differential, using a common methodology, specification,

and data source.6 The far right columns of Table 1 report the full-sample

weighted averages of the nominal and real differentials. Similar to results

reported by Lewis (1986, 179, 186), we find relatively stable wage effects

from 1973 through 1975. However, we find a more marked upward shift than

reported in Lewis for the 1976-78 period. As in the three studies cited by

Lewis, we find a sharp drop in the 1979 estimated gap. Our post-1979 results

show considerable year-to-year variability, with somewhat higher production-worker gap estimates for 1980 and 1983 than in 1979 and 1981. It

appears fair to conclude that the upward trend occurring in the union

differential in the late seventies may have been less marked than that

estimated by some (e.g., Johnson 1984, Linneman and Wachter 1986), and

it was not maintained in the early eighties.

IV. Union Density and the Wages of

Union and Nonunion Workers

Lewis (1986) has argued forcefully that much of the empirical

literature measuring union relative wage effects entangles to some degree

the effects of individual union status and of union density. In order to

separate these effects, variables measuring union density in workers' threedigit industry group and SMSA are included in Equations (1) and (2).

Because inclusion of density variables in wage equations has only recently

5. We have no reason to believe that these results, based on large SMSAs, cannot be generalized.

6. The union variable does change in definition over the period. The 1973-75 surveys asked,

"Does ... belong to a labor union?" The 1976-78 surveys added to the end, ". . . or employee

association." The 1979-81 surveys added, ". .. or employee association similar to a union."

The 1983 survey asked, "Is . . . covered by a union or employee association contract?" These

changes in definition qualify any inferences we make regarding intertemporal changes in the

union wage gap.

141

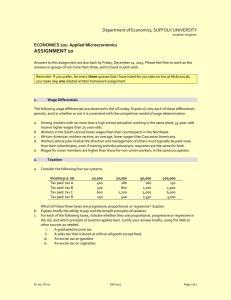

Table 1

Nominal and Real Union-Nonunion Log Wage Differentials: 1973-83

Production Workers

Year

1973

1974

1975

Manufacturing

nominal

real

0.0770

0.0775

663]

[1107;

0.0970

0.0978

[1055; 625]

0.0784

0.0746

[992; 638]

0.1026

1976

0.1038

1977

[870; 626]

0.1229

0.1220

[956; 660]

Nonmanufacturing

nominal

real

Nonproduction

Workers

nominal

real

0.1881

0.1819

[1336; 1391]

-0.0192

-0.0258

0.2262

0.2350

[1214; 1228]

0.1993

0.1917

[1177; 1325]

0.2333

0.2419

[1128; 1267]

0.2950

0.2826

[1257; 1451]

-0.0337

-0.0427

[599; 2797]

0.0060

-0.0045

[599; 2994]

0.0003

-0.0062

[573; 2774]

0.0064

-0.0001

[618; 2876]

[662; 2806]

1978

1979

1980

1981

1983

1973-83a

0.1330

0.1339

[819; 557]

0.0835

0.0837

[540; 358]

0.1037

0.0999

[250; 220]

0.0549

0.0590

[236; 233]

0.1133

0.1152

[281; 243]

- 0.0005

0.2697

0.2577

[1137; 1333]

0.1907

0.1835

[677; 787]

0.2237

0.2142

[371; 485]

0.1457

0.1304

[325; 483]

0.2045

0.1946

[300; 381]

0.0097

d(nom) - d(real)

1973-83b

d(nom) - d(real)

0.0005

0.0074

0.0008

-0.000

[581; 2771]

-0.0515

-0.057

[408; 1654]

-0.0238

-0.031

[206; 961]

0.0097

0.00

[192; 949]

-0.0225

-0.024

[342; 11471

0.0065

0.0106

Note: Samplesizes for union and nonunionworkers,respectively,are in brackets.

a. Unweightedaveragefor 1973-83, calculatedfrom values in the table.

b. Unweightedaveragefor 1973-83, calculatedfrom differentialsestimatedwith regressions

excludingregionaldu

Table 2

Industry and SMSA Union Density Coefficients from Union and Nonunion Real Wage Equa

EquationDensity

Variable

1973

1974

1975

Production workers: manufacturing

0.2032

0.2657

0.1117

Union- Pk(IND)

(3.78)

(4.78)

(1.69)

0.0579

0.1662

0.3183

Union- Pm(SMSA)

(1.32)

(0.32)

(0.94)

0.3574

0.1677

0.3112

Nonunion - Pk(IND)

(3.23)

(2.96)

(1.56)

-0.0997

-0.3133

-0.0603

Nonunion - Pm(SMSA)

(-0.19)

(-0.35)

(-1.04)

Production workers: nonmanufacturing

0.3523

0.4338

0.3587

Union- Pk(IND)

(7.15)

(8.44)

(6.35)

1976

1977

1978

1979

0.2419

(4.42)

0.4578

(2.49)

0.2569

(2.35)

0.1989

(0.65)

0.3204

(5.88)

0.5785

(3.46)

0.1870

(2.12)

0.3681

(1.55)

0.3908

(5.92)

0.2240

(1.10)

0.2519

(2.57)

0.0310

(0.10)

0.2500

0.3966

(3.31)

(3.45)

0.2957

0.1098

(1.33)

(0.32)

0.4056

0.0817

(3.20)

(0.49)

0.0580 -0.3739

(0.17) (-0.79)

0.4482

(7.69)

0.3863

(7.35)

0.4732

(8.34)

0.3292

(4.18)

1980

0.3249

(3.72)

Union - Pm(SMSA)

Nonunion-

Pk(IND)

Nonunion - Po(SMSA)

Nonproduction workers

Union - Pk(IND)

UnionPo-

(SMSA)

Nonunion - Pk(IND)

Nonunion - Po(SMSA)

0.1435 -0.3503

-0.1115

0.0813

-0.2130

-0.1911

0.1450

0.2550

(-1.27)

(0.46)

(0.68) (-2.04)

(-0.53)

(-0.99)

(0.53)

(0.80)

0.7152

0.6651

0.5924

0.5668

0.5845

0.6192

0.5366

0.4234

(7.63)

(7.14)

(6.44)

(7.10)

(7.49)

(4.50)

(7.24)

(3.57)

-0.0205

0.4298

0.0559 -0.2334

-0.1323

-0.0680

-0.5160

-0.0737

(-2.31)

(-0.09)

(-0.64)

(2.03)

(0.31) (-1.05)

(-0.23)

(-0.23)

0.0873

(1.22)

-0.2493

(-0.97)

0.3907

(7.72)

0.0895

(0.55)

Note: t-statistics in parentheses.

0.1270

0.1876

(1.48)

(2.17)

0.0196 -0.0787

(0.06) (-0.26)

0.3104

0.3466

(6.36)

(6.84)

0.1793

0.1532

(1.09)

(0.94)

0.2259

(2.35)

0.0142

(0.04)

0.3256

(6.27)

0.3419

(2.10)

0.2089

0.0954

0.2304

0.0011

(2.50)

(1.21)

(2.38)

(0.01)

0.1470 -0.3340

-0.6410

0.0283

(-1.86)

(0.54) (-1.18)

(0.05)

0.2383

0.3126

0.1812

0.3287

(5.01)

(6.28)

(2.90)

(4.24)

0.2701

0.1221

0.1029 -0.3458

(1.86)

(0.74)

(0.50) (-1.33)

146

The Journal of Human Resources

become widespread, a brief discussion of results seems warranted (we are

unaware of other studies including both industry and SMSA density). Table

2 presents the coefficients y and 6 on the density variables Pk and P,

respectively, from the union and nonunion wage equations.

Industry union density, Pk, is found to positively and significantly affect

both union and nonunion wages (for comparison with other studies, see

Freeman and Medoff 1981, Antos 1983, Moore, Newman, and Cunningham

1985, and the survey by Lewis 1986). The positive effect of increased density

on union wages is typically interpreted as resulting from a decreased labor

demand elasticity. The positive effect of density on nonunion wages is

thought to result primarily from a dominant threat effect in which nonunion

employers must increase wages as industry density increases in order to

remain nonunion. Or alternatively, nonunion firms can pay higher wages

and be at less of a competitive disadvantage the greater is industry-wide

coverage (see Freeman and Medoff 1981 and Moore, Newman, and Cunningham 1985 for related discussions).

In contrast to industry density, labor market (SMSA) union density has

little clear-cut impact on union or nonunion wages (see Holzer 1982 for

more detailed evidence on SMSA density). The greater significance of Pk

than Pm on union wages is consistent with the argument that industry

coverage, but not labor market coverage, impacts on the elasticity of labor

demand. The minor net impact of Pm on nonunion wages suggests that

threat effects from SMSA density, to the extent they exist, are offset by

spillover (or surplus labor) effects that place downward pressure on nonunion wages. While labor spillover effects are likely to be captured by measures of SMSA density (assuming imperfect interarea mobility), they seem

less likely to be associated with industry density.

Comparison of the density coefficients from the union and nonunion

equations in Table 2 also permit inferences as to their effect on the size of the

wage differential. The finding that yu > yn implies the union wage gap

increases with industry density, while 6u > an implies the gap increases with

SMSA density. Surprisingly we do not find the wage gap increasing with

industry density, as theory and limited past evidence would predict (Freeman and Medoff 1981). However, we are reluctant to draw strong inferences

based on the relative magnitudes of the density coefficients, since it seems

likely they are proxying for other omitted variables (Lewis 1986, 153).7

Coefficient estimates on SMSA density do suggest, however, that labor

market density has no significant impact on the magnitude of the union wage

gap.

7. Indeed, Moore, Newman, and Cunningham (1985) find that the nonunion industry density

coefficient is sharply reduced for a sample of manufacturing workers when a firm size variable is

included.

Communications

V. Summary

This paper has provided a detailed analysis of nominal and

real union-nonunion relative wage effects during the 1973-83 period. For all

years, differences between the nominal and real union wage effects are

small. No difference is found for production workers in manufacturing,

while approximately a one percentage point difference is found for production workers outside of manufacturing. Based on these results, it is concluded that for most research endeavors in this area, the costs of considering

cost-of-living differences (e.g., restricting the sample) outweigh the benefits.

Evidence has also been provided on the union wage gap over the 1973-83

period and the effects of both industry and SMSA density on union and

nonunion wages. Union-nonunion wage differentials appear to have widened during the 1976-78 period, but returned to earlier levels after 1978.

Industry density was found to increase significantly both union and nonunion wages, whereas labor market density appears to have little significant

impact on union or nonunion wages.

Barry T. Hirsch

North

Carolina

at Greensboro

University of

John L. Neufeld

University of North Carolina at Greensboro

References

Antos, Joseph R. 1983. "Union Effects on White-CollarCompensation."

Industrialand Labor RelationsReview36:461-79.

Duncan, Greg J., and FrankP. Stafford.1980. "Do Union MembersReceive

CompensatingWage Differentials?"AmericanEconomicReview70:355-71.

Freeman,RichardB. 1981. "The Effect of Unionismon Fringe Benefits."

Industrialand Labor RelationsReview34:489-509.

Freeman, RichardB., and James L. Medoff. 1981. "The Impactof the Percent

Organizedon Union and NonunionWages." Reviewof Economicsand

Statistics62:561-72.

. 1984. WhatDo UnionsDo? New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Giles, David E. A. 1982. "The Interpretationof DummyVariablesin

SemilogarithmicEquations:UnbiasedEstimation."EconomicsLetters

10:77-79.

Holzer, HarryJ. 1982. "Unions and the LaborMarketStatusof White and

MinorityYouth." Industrialand Labor RelationsReview35:392-405.

Johnson, George E. 1984. "Changesover Time in the Union-NonunionWage

Differentialin the United States." In The Economicsof TradeUnions:New

Directions,ed. Jean-JacquesRosa. Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff.

147

148

The Journal of Human Resources

Kennedy, Peter E. 1981. "Estimation with Correctly Interpreted Dummy

Variables in Semilogarithmic Equations." American Economic Review 71:801.

Kokkelenberg, Edward C., and Donna Sockell. 1985. "Newer Estimates of

Unionism in the United States: 1973-1981." Industrial and Labor Relations

Review 38:497-543.

Lewis, H. Gregg. 1986. Union Relative Wage Effects: A Survey. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Linneman, Peter, and Michael L. Wachter. 1986. "Rising Union Premiums and

the Declining Boundaries Among Noncompeting Groups." American

Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 76:103-08.

Moore, William J., Robert J. Newman, and James Cunningham. 1985. "The

Effect of the Extent of Unionism on Union and Nonunion Wages." Journal of

Labor Research 6:21-44.

Raisian, John. 1983. "Union Dues and Wage Premiums." Journal of Labor

Research 4:1-18.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Various years. Statistical Abstract of the United

States. Washington: GPO.

ANDCIRCULATION

STATEMENT

OF OWNERSHIP

MANAGEMENT

R,qu,.;by 39 u.s.c 36851

I1

18.

TITLE OF PUBLICATION

THE

OF

JOURNAL

I.FREOUENCY

OF

St.,

MAILING

Same as

OF

FILING

9/17/86

I

ANNUALLY

Spring,

AODRESS

114 N. Murray

2'DATE

NO.

PU8LICATION

|

sO

3A.NO.OFISSUESPUBLISHED138.ANNUALSUSCRs.PTION

Winter,

MAILING

S, COMPLETE

2 I

IH8

RESOURCES

SSUE

Quarterly:

4. COMPLETE

HUKAN

Madison,

ADORESS

OFFICE

PRICE Ind:

4

Fall

Summer,

OF KNOWN

OF PUBLICATION

S8

$35

Inst:

Dry.Co.ry, S.,..

iS'r..

Z.l.

,nd

Cod

)Nor.

pnn.m

WI 53715

OF GENERAL

OF THE HEADOUARTERS

8USINES5

OF THE PU8LISHER

OFFICES

(N.

p1l.rf

above

S.FULLNAMESANDCOMPLETE

EDITOR{rhr ftm

MAILING

ADDRESSOF PU8LISHEREDITORAND MANAGING

PUBLISHER

N .....

Comp.-re M.a,n-

Prof.

Eugene

EDITOR

4226

Smolensky,

~d Comp/,r

(Nrme

b*t^[

Addr.,.

St..

114 N. Murray

nf UiSrnnst n Press,

ThP Ilnvr-rq1ry

EDITORNm ...nd Co.tp,.. -.r,.~ 4~.dJ

MANAGING

rNOw

Social

M3dison.

UW Madison,

Sciences,

WI 53715

UI

Madison,

53706

Addr&l

Mallrn

7

WI 53706

4226 Soi.1

n,

Thal,

Ma, diso

Soc ial Sciences

UW

,ru m.t . ,rred nd

~ro Imm*dJrtty,rhernder hten

7. OWNER(l! o wned ,y co.pom fo.. It

.... mnd

Jan Levine

FULL

Board

of

NAME

COMPLETE

d edd,~l

MAILING

o)'r o<khiod#n

ADDRESS

Re.enrts

Uw System

AMOUNTOF

WI 53706

Madison,

I PECENT ORMOREOF TOTAL

HOLDERS

OWNING

OR HOLDING

ANDOTHERSECURITY

MORTGAGEES,

. KNOWN OHOLERS

BONDS

MORTGAGESOROTHER

FULL

I

SECURITIES

-.--

o..

..r..

rr

NAME

COMPLETE

MAILING

O TAIL ATSEClAL

9. FOR

NONP

AU THORZ

COMPLETIO

Ilo

ON RFIT

ORGANIZATI

N RATES

ADORESS

2

M

I

2 S?? (rurruc~oru

on mrrn

ddrJ

7772 b

82 cONT.S

8PRECEDING

A

TOTALNO

A. TOTAL

s0. C,p,oES1111Rf^r2739

R.27

8831

778887738773

ATI

PAIDAND/ORREUESTED

CHANGEO 3IRCUL

C

TOTAL

PAID

ANOOR

REUESTED

(&m.o11

tnd 1082)

SAMPLES,

DISTRIBUTION

F. COPIES

NOT DISTRIBUTED

2. Rllu.

from

N-

(Smf

(?12

S

ILING

mTHS

27

ON

DATE

73

7 -68

87

2?34A7

2290

2147

2290

CIRCULATION

COMPLIMENTARY,

E. TOTAL

t 12

ONTn

PRECEDING

AND

o2Cdd

OTHER

FREE

COPIES

24

f

D2

2314

'179

A.*n,

G. TOTAL(S.m o! E. Fl cad

2-aho.ld

. p. t

qM

r

Icrtifythatthe.twttnts mtd.by

m.abovere correct

.ndcomplete

./

4o

l, A)

4.---_

2 739*

.W.^.f

2773

-__o-d

R